Project Humanities is a university-wide initiative at Arizona State University that strives to connect people through talking, listening, and connecting about the humanities. Every semester, Project Humanities chooses a theme that will guide their kick-off week and subsequent semester. Kick-off week for the Fall 2013 semester will run from September 16-21 with the focus of “Humor… Seriously.” Advertising intern April Hanks had the opportunity to conduct a phone interview with Neal Lester, Foundation Professor of English at Arizona State University and Director of Project Humanities.

Project Humanities is a university-wide initiative at Arizona State University that strives to connect people through talking, listening, and connecting about the humanities. Every semester, Project Humanities chooses a theme that will guide their kick-off week and subsequent semester. Kick-off week for the Fall 2013 semester will run from September 16-21 with the focus of “Humor… Seriously.” Advertising intern April Hanks had the opportunity to conduct a phone interview with Neal Lester, Foundation Professor of English at Arizona State University and Director of Project Humanities.

April Hanks: How would you explain project humanities to someone?

Neal Lester: Project Humanities is a university-wide effort to demystify and to promote the relevance of humanities research and public programs across all campuses and into the surrounding communities. And we do that through a number of strategies that are research-specific as well as public programs that engage diverse communities. It’s all year round and it has been in place for about three years.

AH: How did Project Humanities begin?

NL: The germ of the idea began in fall 2010 and that’s when we assembled. I served as Dean of Humanities in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at the time and one of my charges was to make humanities more robust. It was at a time when a lot of humanities programs across the country were being cut because of budget and… around the country they seemed to be chopping at humanities courses first. So what I figured I needed to do in terms of making humanities more robust was to first sort of take humanities out of this notion that humanities happens within a classroom. [I needed to show] that humanities were bigger than discipline and that we could actually talk about humanities across all disciplines. And so that became sort of the focus. How do we talk across disciplines, how do we talk within disciplines so it’s not as if literary scholars are always talking with historians or historians are always talking to religious studies scholar? So there was an effort both to talk within disciplines, but also to talk beyond and across disciplines about those kinds of questions that humanities ask. And they’re not formulas. They’re not always black and white. But it’s to find meaning in those sort of grey spaces between, say, STEM disciplines and look at humanities as a way of basically helping us better understand what is going on in our lives and the world.

AH: You mentioned that Project Humanities reaches out to the community…

NL: Communities. I get a little bothered when we sort of make community monolithic, because I don’t know what that means when we talk about the community. Because what Project Humanities tries to do is reach out to multiple communities and my personal sense is that each individual is a member of multiple communities simultaneously. We can certainly talk about communities within ASU, we can also talk about communities outside and beyond ASU.

AH: How does Project Humanities engage with communities outside of ASU?

NL: First of all, we have about 100 programs a year that we either sponsor or cosponsor. We’ve done Project Humanities events at churches that were not necessarily faith-based programs, we’ve had film screenings at one of the churches downtown, we had another public program at one of the cafes, the Fair Trade Café, we did another at Sunnyside Diner in Ahwatukee, we do things at the library, we had a program that was actually at The Lot, which is downtown Phoenix outside, we had one of our first programs that engaged the community at the Phoenix Youth Hostel, in addition to having programs on campuses across all four campuses. So that’s one way.

Not only do we have programs at these other places, but we also invite people from these communities into ASU to sit on panels or into ASU to give a lecture or to participate in a conversation. For “Humor… Seriously” we actually have a representative from Tempe Improv as well as the National Comedy Theater, I believe, who are coming in to talk in the business school about the business of humor. So it’s not as much about being funny or talking about humor and how humor is done, we have other workshops about that, but this is how do you market humor. How do comedy clubs survive? How do improv groups survive? What is the entrepreneurial aspect of humor? So these are not people who are ASU people, they are coming from the outside. We also engage with national communities. So we don’t just deal with the local but we try to make sure that the local expertise interfaces with the national. So we have national speakers coming in, we have people leading workshops who are national experts. We also talk about the international communities and we have a visiting scholar now from Norway. And our Hand campaign, which is the t-shirts: people wearing the t-shirts and then sending us pictures from all over the world. So there are multiple ways we engage with communities outside of ASU but also communities inside of ASU.

AH: You’ve mentioned several times that the focus for this semester is humor, so how did Project Humanities decide to focus on humor this semester?

NL: We have a signature event: biannual kick-offs. And rather than doing what some universities have done, which is to just sort of throw anything and everything that has to do with humanities into a segment of the semester, we decided, this was a steering committee and I three years ago, that we would try to have some kind of thematic focus. But a thematic focus that would allow anybody doing anything across disciplines, communities, and professions.

So the first one we did, which launched it in spring of 2011, was “Perspectives on Place.” And that theme is interesting because when we started Project Humanities, it was to address a number of things, not only about the place of humanities in higher education when parents and students are asking where you’ll get a job when you major in English or French or Spanish or even art history. So it was the place of humanities in that conversation. The other part had to do specifically with the southwest. At the time, Arizona was going through some really difficult political and social conversation about racial profiling, about immigration, about attacks on ethnic studies. SB 1070 was high on everybody’s list and there was this narrative circulating that Arizona was not very hospitable to difference, and cultural difference at that. So Project Humanities was a conscious effort to try to address some of those issues, to say “here’s a different narrative about what’s going on in the southwest, in Arizona, and at Arizona State University.” So in many ways the idea of the project was focused around a particular need to address a number of things that were specific…

So then we did one on American music, and we had a number of performances. We had Blues at the MU, we had conversations about blues and memory, we had performances. I remember one in particular where we had a sold out audience in Old Main, where we had performances of gospel, of barber shop, and of poetry and rock. But punctuating each of those performances, and they were actually diverse, were music historians’ views of how these different genres connected. So it wasn’t just a series of performances as if you’ve been to a concert.

Then we had another one on truth, and a lot of these come out of what’s happening in the world, so at the time it was about whether or not truth is overrated. People are always saying “tell the truth and nothing but the whole truth,” so we sort of explored that. What does it mean to do truth in art? The students had something about white lies: what does it mean when you’re just telling a little white lie? So there’s all these efforts to talk about truth.

Then we did one on “Are We Losing Our Humanity?” And that one has been the one that has resonated in more far-reaching ways. And I say that because we built a summer film series around it, which is a film per month at one of the public libraries in Phoenix, not always at the same place. And that led to a number of public lectures that I did and continue to do because people are actually trying to give meaning to some of the stuff that doesn’t make sense, whether it be a Tucson tragedy, or Aurora, Colorado shootings, or Newtown, Connecticut, or any number of things that are happening in our own neighborhoods.

So from “Are We Losing Our Humanity?” we moved into for the spring, “Heroes, Superheroes, and Superhumans.” And that seemed a natural fit because often times wherever there’s great tragedy we also hear these stories of great heroism. And we were also able to move not only into comic books, but also in terms of veterans as heroes, teachers as heroes, everyday heroism. And we created a number of activities around the theme.

From that, the humor felt like everybody could bring something to the table on humor. And it was not just comedy, so we deliberately didn’t name it comedy, but we tried to look at humor not only from a scholarly perspective, but also from a performance perspective. So we’ve got a couple of open mics, we’ve got workshops, we’ve got film screenings, we’ve got lectures, we’ve got a funniest teacher contest that’s coming up. So the idea is to try to find something that everyone can potentially participate in so that it’s not something that excludes people.

AH: What is your future vision for Project Humanities?

NL: Well, I want Project Humanities to first of all be more nationally visible. I want it to be one of the leaders when people talk about humanities nationally. Somebody will say, “What is Project Humanities doing?” or “What would they say about this?” And I also want it to be a center for collaboration across disciplines and across professions and communities. We’re writing a number of grants now, so we can expand the reach of Project Humanities. We don’t have a very large staff, but we have a growing staff of students who are both volunteers and also student workers. And I think more people are knowing about Project Humanities. I mean, I’m so excited that three years ago we started with about 200 Facebook likes. This summer, we had about 600 and of right now we have 936 likes. And our announcement about Bill Nye went viral immediately because Bill Nye is going to be one of our guest speakers this semester, talking about humor science and science humor through the lens of humanities. So that’s one indication, I’d like for that to be more robust. I’d like for us to be more nationally visible and I’d like for people to know when they’re going to an event, “Wow. I get humanities. Humanities really is important.”

For more information on Project Humanities or their fall kick-off events, check out the Project Humanities website (http://humanities.asu.edu/) or Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/projecthumanities).

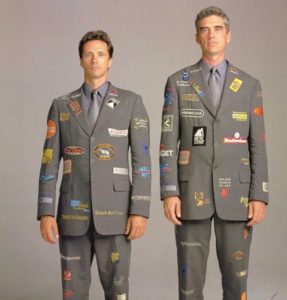

On September 7th, the Scottsdale Art Museum will be hosting The Art Guys, a comedy duo that uses humor to demystify the art world. This lecture is a free event that starts at 7PM. Find out more information about the event

On September 7th, the Scottsdale Art Museum will be hosting The Art Guys, a comedy duo that uses humor to demystify the art world. This lecture is a free event that starts at 7PM. Find out more information about the event