It’s never too late to be what you might have been – George Eliot

When I was fifteen, I saw South Pacific and, imagining my name in lights, I signed up to audition for Play Pro, my high school drama club. But before my name was called, I chickened out, fleeing to the bathroom. My best friend, performing Juliet’s balcony speech, was just too good.

When I was fifteen, I saw South Pacific and, imagining my name in lights, I signed up to audition for Play Pro, my high school drama club. But before my name was called, I chickened out, fleeing to the bathroom. My best friend, performing Juliet’s balcony speech, was just too good.

That was that, I thought—until a friend, fifty years later, asked me to join OnStage, a group of closet actors, all over 55, who met weekly with a director named Adam.[1] “We learn theater techniques and do documentary theater,” she said. Which meant gathering stories from the community about senior memories and experience and performing them at libraries, schools, senior centers, hospitals— “whoever wants us.”

I’d just retired from fulltime teaching and this sounded like fun, something different —with “scripts” more like stories you tell over lunch or hear on a bus. What do I have to lose? I thought. The pressure of youth was off.

Every Wednesday afternoon, at the Community Room, I do theater games like becoming a watermelon to my partner’s grapefruit, each of us conversing with our one word –“Watermelon!” “Grapefruit!” “Watermelon!” “Grapefruit!”—saying them loud and soft, sexy and timid, fierce and giggly. A whole range of emotions, just like that.

I like morphing into someone else, sometimes younger, sometimes older—all is possible. I like moving my body on stage, feeling braver than I did at fifteen. And I like how audiences connect to our stories as if we were telling theirs.

Take the large, wild-haired grandmother at the Metuchen Library, who came to see “You Win Some, You Lose Some” –-about everything from losing your false teeth on the subway to dating after 60, to end-of-life decisions. Afterwards, in a lively post-show discussion, she told everyone: “The beach week story is just what happened!” She pointed to me (I had played the grandmother). “Like you, I didn’t want to go to beach week again. Like you, I told my daughter that the bed too uncomfortable. And then she, too, dialed my grandson.” I tried to explain it isn’t really my story, but she ignored me, “How can we say no, right?” She delighted in having her story validated, and I delighted in her delight.

A week later, on a roll, we enter an assisted living/nursing home, our first. Wheelchairs, maybe thirty of them, are lined up. Some residents are sleeping; most are just staring straight ahead. No one except the aides seems to interact with anyone else, and talk is about rearranging wheelchairs. Please God, don’t let me land here! we whisper to each other as a squat, indifferent man hurries our group into a cluttered room beyond “the theater space,” really the cafeteria. A guy is mopping the floor, something easy to slip on if it doesn’t dry fast.

No post-show discussion, we decide quickly. These people don’t talk; they don’t smile. It is too risky. The floor hasn’t quite dried, but we start anyway–with the refrigerator buzzing and the loudspeaker interrupting every few minutes. Some people keep sleeping (Are they drugged?), but others smile and nod, especially about stories of love, marriage, and sex. Lines like “I learned that a second marriage can be better than the first” get a big whoop.

Forty minutes later we take our bows and head towards the glass front doors as if lingering is contagious. I edge past the wheelchairs waiting to roll back down the long corridor, and that’s when four people take my hand, grip it, saying thank you for coming. Their silence was not a given, their isolation not inevitable. They want to be reached, need to be reached, and we…I… fled too quickly—as I did when my grandmother was in a place like this. I couldn’t conjure up her elegance and what her magic cookies tasted like—and that scared me. I was nineteen.

Suddenly I realize our mistake. We should come back here for a post-show something, despite the sleepers and the silence—for those who gripped my hand or might, you never know. Theater can do that, erase the self of now enough to become who we might be—or once were.

We’d have to ask our director Adam to help, by using his magic to unlock some of what he unlocked in us: that bit of risk that leads to a smile.

It’s worth a try. After all the boundaries between ‘them’ and ‘us’ are fading with each passing year.

[1] Adam Immerwahr’s is Associate Artistic Director at McCarter Theatre in Princeton, New Jersey and Resident Director at Passage Theatre in Trenton, New Jersey.

To see learn more about Onstage, go to www.onstageseniors.org

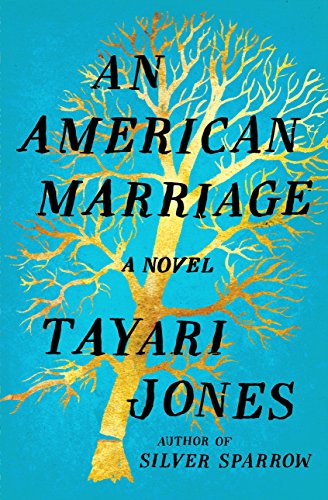

Today we are happy to share the news of past contributor Tayari Jones. Tayari’s latest novel, “An American Marriage,” published January of last year, is continuing to gather awards and nominations. Already a 2018 Oprah Book Club Selection and a notable book from both The New York Times and The Washington Post, the novel most recently won The Lost Angeles Times and Festival of Books’ Fiction Prize. “An American Marriage” follows a young African-American woman as her husband is wrongly accused of a crime and sentenced to twelve years in prison.

Today we are happy to share the news of past contributor Tayari Jones. Tayari’s latest novel, “An American Marriage,” published January of last year, is continuing to gather awards and nominations. Already a 2018 Oprah Book Club Selection and a notable book from both The New York Times and The Washington Post, the novel most recently won The Lost Angeles Times and Festival of Books’ Fiction Prize. “An American Marriage” follows a young African-American woman as her husband is wrongly accused of a crime and sentenced to twelve years in prison. Today we are thrilled to share news of past contributor Katie Cortese. Katie’s essay, “Four Pink Plus Signs,” has been included in the November 2018 issue of Gravel. You can read Katie’s essay in their website

Today we are thrilled to share news of past contributor Katie Cortese. Katie’s essay, “Four Pink Plus Signs,” has been included in the November 2018 issue of Gravel. You can read Katie’s essay in their website

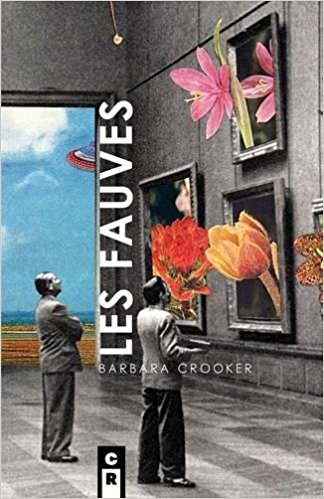

Today we are happy to share that past contributor Lee Ann Roripaugh has been recently featured in

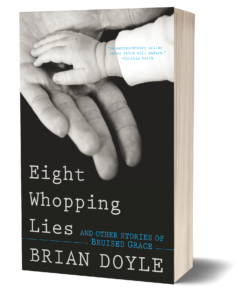

Today we are happy to share that past contributor Lee Ann Roripaugh has been recently featured in  We will always remember Brian’s abundant generosity.

We will always remember Brian’s abundant generosity.