I asked a seven-year-old girl once what the word “imagination” meant, and she said it meant “going further than you can think.” I have been pondering her answer for thirty years. What is it to go “further than you can think?” Is there a thinking beyond thinking, beyond words and that nonstop flow we call “consciousness?” Well of course there is. And I feel it every time I sit down to write or draw. There is something about blank paper that makes me feel like a small blue rowboat about to push off into a wide, bottomless lake, to break the water with my wooden nose.

I asked a seven-year-old girl once what the word “imagination” meant, and she said it meant “going further than you can think.” I have been pondering her answer for thirty years. What is it to go “further than you can think?” Is there a thinking beyond thinking, beyond words and that nonstop flow we call “consciousness?” Well of course there is. And I feel it every time I sit down to write or draw. There is something about blank paper that makes me feel like a small blue rowboat about to push off into a wide, bottomless lake, to break the water with my wooden nose.

When I was a kid, I used to draw incessantly. My older brother was off playing. My parents were off doing whatever grownups did, which I always pictured as occurring up in the sky for some reason. If my dad were at work, I’d see him at his desk in a building way up in the clouds. Even if I had actually visited his office, I’d picture it up in the sky. I want to say that I knew his office was on land, but, truth is, what I knew was that his office was somewhere in the sky. There is no explaining this sort of thing. It isn’t about facts. It’s about knowing. Or, perhaps, going “further than you can think.”

Anyway, I drew constantly at the big, low wooden table in my upstairs bedroom with the window looking out on the yard. I always drew with my back to the window. Apparently, I didn’t need the “outside world” for inspiration; blank paper was enough, plus a box of Crayola crayons, the jumbo box. To this day, I can remember the thrill of drawing a battleship. I wasn’t a big fan of war, but I loved drawing battleships. My brother, who was a year older and a foot taller, was off with the big kids – the BIG KIDS. And I imagined the “BIG KIDS” as a country where mythical, semi-gods jousted and had swordfights. So, it was easy for me to see why my brother wouldn’t want me tagging along. At eight years old, I, of course, knew that “BIG KIDS” wasn’t a country and that they didn’t actually joust there. But that was a mere understanding, a puny sort of knowing, compared to the deeper, finer knowing that came from the place in me that knew that the big kids did joust or could joust or jousted when no one was watching.

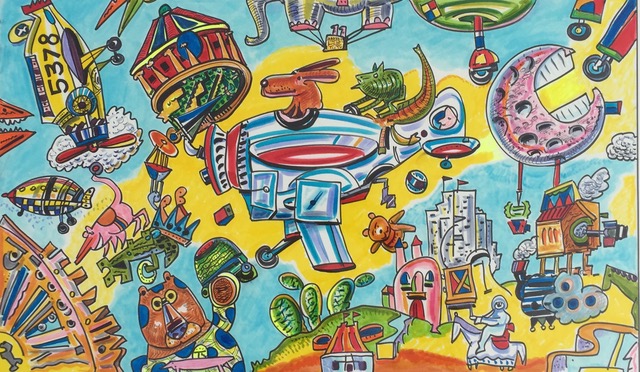

It was the same place from which I drew battleships that lunged and plowed through the salty waves and weren’t afraid of anything. Or intergalactic space vehicles that could land anywhere and send messages back in code, a language that I, alone, could understand. Or ancient fire-breathing, mind-reading, baseball-playing tyrannosaurus rexes. Or dolphin acrobats that could sing songs inside out. The place from which I drew was beyond logic, reason, words, worry, self-pity, self-criticism, or any need to “succeed.” It was a vast, secret place of freedom and confidence, mystery and surprise, joy and anticipation lodged in a tiny ball of infinity that I carried with me wherever I went. It is the same place from which I now write. If I am lucky. If my need to do well and look good doesn’t get in the way. But, at eight, with a crayon in my hand, I was God: creator of worlds and worlds within worlds. Not a lonely, runty kid.

Everything I ever learned about writing I probably learned from drawing, from drawing at the big, wide upstairs table when I was a kid, when I was God, and knew it. Knew it quietly. The same way your tongue knows the back of your teeth. Of course, I learned the rules of writing in school, which is where I learned to hate writing. I “learned” to write for the teacher, for the grade, for the grammar police. Speaking of which, I am a big fan of the grammar police. Just at the end of the process, not while I am trying to be some place beneath or beyond my “thinking.”

Spewing out gorillas and battleships and dinosaurs and space vehicles and flying buffalo, I wasn’t following anyone’s rules or trying to get anything “right.” I lost myself in that most sacred of all things – PLAY. Naturally, drawing has rules. Writing has rules. Brushing your teeth has rules. So, learn the rules. But don’t let them keep you from dropping down your own, personal rabbit hole.

I started to write seriously when I was nearly fifty. By accident. I was slamming my van door when the phrase “He lived in Edward G. Robinson’s head,” popped to mind. I had no idea my mind was thinking about Edward G. Robinson, the nineteen thirties’ movie gangster. I was just slamming my van door. Next day, I got a pen and paper and, beginning with the sentence, “He lived in Edward G. Robinson’s head,” I started writing and writing and writing. I wrote about a guy working in an amusement park on Gangster Lane in a giant stucco replica of Edward G. Robinson. I wrote the guy’s observations about life, death, bugs, mice, sex amongst houseflies, border control, malaria, King Arthur and his famous (make-believe) dog, junkyards. I just wrote. And every time I “hit a wall,” I said to myself: “It doesn’t have to make sense,” and I burst free. “It doesn’t have to make sense”became my mantra, my stick of dynamite, to blast through barriers. I wrote and wrote: eight hundred and fifty pages by hand. I called it “In the Nostrils of an Icon.” Took about a year.

I was working as an educational consultant at the time, and everything I did in the schools had to be “objectives driven.” You had to know what you were going to say, say it, and then check that people got what you said. Which, turns out, was the opposite of my own creative process. I’d come home from work and mess around in the “backyard” of my mind. I’d let my imagination go nuts. My ability to go “crazy” kept me from going crazy. And I realized the biggest creative secret of all (for me) — MY MIND HAS A MIND OF ITS OWN. It was something I knew as a kid with a crayon in my hand, but learned, later, to forget or not trust. My mind, actually, has a LIFE of its own. It’s a kid who wants to go to the park and swing on the swings and go ape. If I let him, all is well. If I don’t and don’t regularly spend time creating, all isn’t well.

I wrote a second book, “Memoirs of a Gorilla,” all about the difference between the freedom of time and the freedom of space. School seems to make a grand distinction between the intellect and the imagination. But there IS no intellect without imagination. Again, I just trusted the kid in me. And then I started writing short stories: about three hundred of them. I went to a local coffee shop and wrote. Writing at home was too solitary for me, but writing in public (at a table near a window away from people) was heaven. I’d wake up, gobble down breakfast, and hurry to the café. I couldn’t get there fast enough. The place in me “beyond thinking” was already brewing up a story. The houses and streets and billboards along the way were all in Technicolor. By the time I got to the café, my eyesight had practically tripled. I’d pour my own coffee, and the “little kid” in me would be so damn happy, I could explode. The gorillas and dinosaurs were all flying around in my head. I didn’t think I was a “Writer,” not a writer with a capital “W.” I just wanted to write.

I’d sit at the table near the window, wave at the sky above the building across the street. My mom had passed away eight years earlier, and I’d wave to her in the sky. “Hi, Mom.” I’d say, “I’m doing it.” Which meant I was writing. My mother was a brilliant writer, but because she didn’t feel she was a writer with a capital “W,” she never let the little creative kid in her play. Now, of course, I found my own ways of not trusting the “kid” in me, the ball of genius that wants to break the rules and fly off the edge, to go beyond “reality” to unknown truths. So, for hours a day, I just took the old blue rowboat out onto the lake. I felt giddy and indispensable. After four hours of writing I would walk around the block and involuntarily start skipping.

See, that was the part I didn’t learn about in school. That writing wasn’t a competition. And it wasn’t serious because it was important. It was serious because it was fun. The sort of fun where, afterward, I felt more myself because I was being exactly myself. Of course, it’s not always fun. Often nothing comes. Nothing at all. But I know I am in the right place, at least, the place where something can come. I always start with the first thing that pops into my head, usually something odd and specific. Like how I used to draw. Like this recent beginning of a story that I wrote in a white heat because I was pissed at something:

I live in the lavender gut of a horse, a beating heart just beyond the wall. And beyond the centuries-old loftiness that is horse, two old ladies sip tea on a white porch in the crabapple South, hoping for something that might squirrel up out of the ground, the age-old ground, the southern ground, the ground at the top of a hill: a thin line of angels listening all boneless and hospitable from above, managing nothing with their tiny, modest, angel hands, hands that might just as well be days of the week. The long-gone Civil War is wearing a small red and gold cap once worn by an organ grinder’s monkey.

Where did it come from? What does it mean? Where is it going? Well, to me, it comes from the place of “flying buffalo” and “mind-reading dinosaurs,” the place from which I used to draw as a kid and still do – a place beneath words that goes further than I can think.And, hopefully, I can wrestle and shape the story into something made of flights of imagination and depths of emotion.

Yes, I learned to write by learning to draw, by learning to observe and imagine. The world is always brand new. Just observe and imagine. A number two Ticonderoga pencil becomes extraordinary if you stare at it long enough. And language doesn’t have to merely describe and explain. It can re-wire everything. Because we don’t just live in a world where “dogs bark.” We live in a world where “bogs dark.” In the end, I write from the place where children live– the senses, imagination, and emotions. I write from that place we all know from long ago, the place the seven-year-old girl called “going further than you can think.”

Today we are pleased to feature author Timothy Reilly as our Authors Talk series contributor. In this podcast, Timothy discusses the inspiration behind his short story, “The Task at Hand,” calling it a “nod to the old Grail romances.”

Today we are pleased to feature author Timothy Reilly as our Authors Talk series contributor. In this podcast, Timothy discusses the inspiration behind his short story, “The Task at Hand,” calling it a “nod to the old Grail romances.”