- The high school classroom is standard issue. I’ve grown up in this mill town, but it’s really dying now. None of the students around me in this creative writing class have aspirations to become a writer. They want to go to college and get a job that they won’t get laid off from. My teacher Mr. Moore tells me: it doesn’t matter where you go to school. Anywhere you go, you’ll find great professors to work with. He says, yes, I think you have what it takes to become a writer.

- I’m in a standard issue professor’s office for my mid-semester conference in fiction 101. It’s probably the first workshop I’ve ever taken in my life. The professor looks up at me, squints, and says: The problem with you is that at some point in your life someone told you you were creative.

- I’m 23 years old and about to get into my boyfriend’s puke green Chevy. It’s parked in my parents’ driveway. We’ve stopped to visit them as we head west after I’ve graduated from the University of New Hampshire. We’ll travel across the country for months without any real destination, although we end up in San Francisco for 4 years. My parents don’t understand what in the hell I’m doing, although they wouldn’t say it that way. My dad tells me: always make sure you’re making enough money per month so that one week goes to rent, one goes to utilities and bills, one goes to savings, and one is for spending money. I follow this advice for years and in many ways it’s how I am able to write and work and live and be happy in many different places.

- My friend Pam on many different occasions: If you’re not having fun, leave.

- I’ve just met my roommate Mallory Tarses at Sewanee Writers’ Conference and by dinner time everyone thinks we’ve been friends forever. I write flash fiction, have been writing it for many years. Everyone tells me I need to write a novel. Everyone. Mallory says, or why not just get really, really good at writing flash fiction?

- At that same conference Tim O’Brien says: Don’t forget to look around while you’re in there writing the story, take the time to look around.

- My friend Jonah Winter: Knock it off.

- I’m four years out of graduate school and living in Pittsburgh with a real job working in museum education. It’s 40+ hours a week and stressful. I feel lost so I email my mentor Marly Swick (See #1) and tell her I’m ungrounded and out of touch with any kind of national writing community. She says, “Why don’t you apply to some writing residencies? I think it’s time for you to do that.”

- I’m at Atlantic Center for the Arts studying with Jim Crace and a great group of fiction writers. Armadillos rustle through the grasses below the boardwalks. Jim Crace says: “Slow down. Look at each sentence. Craft each sentence. Vary the length. Think about word choice. Avoid repeated words. Use active verbs. You already do this instinctually, now I want you to do it deliberately.”

- Pam Painter: Start with a list. A list is never intimidating.

- I’m running the Gist Street Reading Series in Pittsburgh. The writer John Dalton gets up to read from his debut novel Heaven Lake. He finishes and immediately sells out of books. Later he tells me: Summarize the novel in your introduction and then read a strong section that doesn’t logically follow from the summary. People buy books because they want to find out how the two connect.

- There’s a big round table and 21 of us sit around it. The Creative Capital retreat is like a boot camp in professionalism for artists. They tell us: Always introduce yourself using your first and last name. They tell us: Have a 1-year plan and a 5-year plan. They tell us: If you’re not being rejected, you’re not working hard enough.

Life

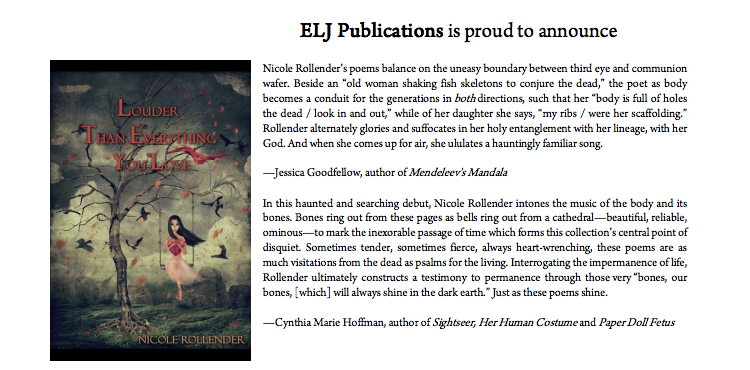

Congratulations Nicole Rollender

Congratulations to SR Contributor Nicole Rollender on the release of her first full-length poetry collection, Louder Than Everything You Love (ELJ Publications), available now from ELJ Publications.

More than anything else, Louder Than Everything You Love is about transformation. The narrator in these poems is many: women who talk to the dead, women who mourn dead mothers and grandmothers, women suicides, women who’ve been raped/escaped rape, women who cradle premature babies, women who suffer depression, women who prepare the bodies of the dead, women who exist between their children’s bodily needs (“this body-psalm of need the only holiness I know”) and saints’ incorruptible bodies.

These women also live inside themselves, contending with the wolves within, asking: “How do I measure the body’s gardens form within its bone fences?” The dead, the living and the divine inhabit this collection – they’re looking for kinship, remembrance, for some kind of communion. The poems in Louder Than Everything You Love are about the struggle of living in a body, being a parent, trying to find the balance between what our lives on earth mean/what it means to come to terms with dying.

Louder Than Everything You Love is also available for direct purchase from Nicole for $18.99, who will sign it and send it from her house free of shipping with a copy of her poetry broadside “This Is How to Feed Your Young.”

Read more of Nicole’s poetry in Issue 15!

Guest Blog Post, Andrew Galligan: Mr. Know-It-All

Thanks to my immeasurable fear of poetry (I’m a poet), I’ve read a lot of prose – both fiction and non – in the last year or two. (And believe me – I’m making no judgment on the difficulty of reading or writing either). Piling up the paragraphs over that time, I’ve developed for the first time in my serious reading life a handful of prose preferences. They are not genre or period related, but more or less determine whether I’ll go on reading a piece. One potential deal-breaker, beyond careless sentence-making or writers writing about writers, is the omniscient narrator. Perhaps jealously is at the root, but this idea of knowing everything is just perverse!

Thanks to my immeasurable fear of poetry (I’m a poet), I’ve read a lot of prose – both fiction and non – in the last year or two. (And believe me – I’m making no judgment on the difficulty of reading or writing either). Piling up the paragraphs over that time, I’ve developed for the first time in my serious reading life a handful of prose preferences. They are not genre or period related, but more or less determine whether I’ll go on reading a piece. One potential deal-breaker, beyond careless sentence-making or writers writing about writers, is the omniscient narrator. Perhaps jealously is at the root, but this idea of knowing everything is just perverse!

Often when a seer is telling me a story, patiently stirring that cauldron of latent symbols, I find him more prone to early, unnecessary or heavy-handed foreshadowing. The temptation is too large to place emphasis on minor events, to pause the story and thread an extra detail into a character or place. They may be small shovels, but they’re still smacking my face. It’s like hearing Bon Jovi’s voice come over a nice, warming rock riff – right away I’ve got a pretty good idea where this is headed.

Regular consumers of story – book, TV, film, barroom or otherwise – are trained to search for symbols and signposts, driven by the potential self-fellating glee of “figuring it out first.” So, unnatural emphasis always arrests the reader, drawing increased attention like a car crash under a full moon. Emphasis in everyday life comes when and where our minds and hearts apply it, without the guidance or intervention of a third party. The granular events of each day fall upon us organically, settling into piles in our minds as guided by our own passions, distastes, prejudices and hopes. Within that unrelenting cascade, we can find ourselves ascribing deep meaning to a minor event, only to have that depth truncated or in some way altered by future events. We make our own storytelling mistake. The grain has to change piles.

Coming to understand people and places integrated in a story through eyes at a time – a single vision or set of views always complicated by emotion and by biased & unreliable memory – is what we experience in everyday life. When we as readers have no choice but to see characters exclusively through their words and actions, to develop and deepen our impressions of them, we go through an iterative rigor that mimics how we come to know the real folks we collide against. Some may find comfort in an omniscient narrator’s IV drip of information that stitches a story together, but to me it’s a prescription much less satisfying for the exact reason that we as readers lose the opportunity to do that work ourselves. What we’ve gleaned of human behavior through the rugged course of personal living matters less than how practiced we are at reading the cards in a narrator’s hand.

Coming to understand people and places integrated in a story through eyes at a time – a single vision or set of views always complicated by emotion and by biased & unreliable memory – is what we experience in everyday life. When we as readers have no choice but to see characters exclusively through their words and actions, to develop and deepen our impressions of them, we go through an iterative rigor that mimics how we come to know the real folks we collide against. Some may find comfort in an omniscient narrator’s IV drip of information that stitches a story together, but to me it’s a prescription much less satisfying for the exact reason that we as readers lose the opportunity to do that work ourselves. What we’ve gleaned of human behavior through the rugged course of personal living matters less than how practiced we are at reading the cards in a narrator’s hand.

One appeal could be control. The omniscient’s control allows us to implicitly and unquestionably trust what we’re told; the facts of people and place must be true as stated, and only an unexpected sequence of events can catch us off guard. [Hey, the cat just puked up a skeleton key!]. That control engenders comfort because, for just once, we’d like not to be caught off guard. In my own life, I’d love to control the sequence. To orchestrate the order in which my impulses and emotions deploy, or when shit happens so I can be prepared. If I could stipulate when I’d feel fun, intrigue, sex or horror (or all the above?!), that would beat the defeat of always reacting.

It’s probably because of Faulkner that I started to really see and feel differences in narration. He’s certainly on the far end of the spectrum, utilizing a myriad of voices, heavy dialect, stream of consciousness and nonlinear narration (unannounced flashbacks!) that jam the reader through at times paralyzing confusion. Most of us have enough confusion in our lives; I can certainly understand the desire not to grapple with it, too, when spending time to unwind and escape with a piece of literature. The difference to me is how powerful the experience of reading can be when it more closely meets that everyday I claim I’m trying to escape. What I’ve come to realize is that I read simply to try to understand my life and all its whys. I’m there in that story for comfort, for information, for insight. The confusion is not arresting, but familiar, and I want it so I can continue to turn the pages in search for a little more certainty I can use when I wake in the morning.

Guest Blog Post, Marcus Banks: Deepening

Living in Northern California, I’ve enjoyed a fair number of wine tastings at vineyards in Sonoma and Napa. For many years I preferred white wines to red. The white wines were crisper, sweeter, easier on the palate. The reds were more subtle, more complicated, altogether more work. I’d drink the reds with a sense of duty, the whites with an air of expectation.

Living in Northern California, I’ve enjoyed a fair number of wine tastings at vineyards in Sonoma and Napa. For many years I preferred white wines to red. The white wines were crisper, sweeter, easier on the palate. The reds were more subtle, more complicated, altogether more work. I’d drink the reds with a sense of duty, the whites with an air of expectation.

Over time this changed. These days white wines seem childish, too easy. Bring on those sophisticated red grapes! I can handle them now. Life is complex and multi-layered, meant to be understood and appreciated gradually. Our alcohol should be similarly complex.

And our writing too. I often cringe when I read essays or blog posts that I wrote years ago. Those posts–such as when I excoriated the GOP in 2005 for exploiting the decline of Terry Schiavo–were fun to write. The blood boils, the pulse races. But after the adrenaline rush subsided, I’d ruefully realize that my latest missive had added more heat than light. Back then it was acceptable for my writing to be polemical more than polished. Sometimes this was even the point.

My writing began to mature in 2009, when my first marriage ended after eight years. During this year my blog became a public sanctuary, a safe place to sort through the welter of emotions that accompanied this life-changing event. Eventually Superstition Review was kind enough to publish an essay I wrote about that painful year, entitled “Divorce and Gratitude.”

During this year my writing deepened. It went from white wine to red. I consciously examined the divorce from every angle, coming to terms with it however I could. No pulse racing writing came along that year; instead there was a series of lengthy, slow-to-develop essays.

It often seemed that friends were angry or wanted me to be angry, but I resisted this beckoning toward bitterness. These days I wonder if I exaggerated this “beckoning” in my own mind, as a way to give my writing something I could respond to. If so, it worked.

Life moves on, sometimes in the most wonderful ways. Four years later I am very happily remarried, whereas four years ago I was convinced I would die alone. I’m still proud of that year’s writing, but from this remove I can’t help but notice its solipsistic nature. My writing that “divorce year” was reportorial, insular, brooding. This interiority was a necessary transition away from the fiery blog posts of yore, but I’m glad those days are over.

These days my prose is outward looking, and the reports about my personal life I do draft are light. The beautiful thing about writing–this privilege of stringing words into meaning, and hopefully moving our readers–is that it is capacious enough to cover all stages of our lives. Now my words are more measured, more polished, but just as passionate and hopefully (a bit) more wise. Growing older has its rewards, on the page and in life.

The Shape of the Eye, Memoir by George Estreich

Issue 7 contributor George Estreich recently published a new memoir, The Shape of the Eye, in which he describes the blessings and challenges of raising his daughter Laura, who was diagnosed with Down Syndrome. Estreich is known for his book of poems, Textbook Illustration of the Human Body, which won the Rhea and Seymour Gorsline Prize from Cloudbank Books.

While writing Shape of the Eye Estreich was faced with new challenges, both technically and personally. Having a strong background in poetry, Estreich found writing a memoir to be both a foreign and familiar experience: “When I wrote poems, I was mainly concerned with language, line by line and word by word […] In a way, I was still writing poetry, trying to get each sentence right, to find the right word and metaphor and form. At the same time, those formal choices became part of a larger goal.”

Creative nonfiction can have its own challenges, especially when the topic is so personal. Estreich commented on that intimate quality of Shape: “It’s odd to have written so much autobiographical work, in poetry and prose, because I think of myself as a private person. So there was a tension between necessary truth-telling and privacy. Also, if one is writing about people one cares about, and one acknowledges that true stories can do harm to relationships, then writing and family are in tension too. Storytelling is an ethical act. I don’t have a formula for resolving these tensions, and I don’t think there is one, but these issues were never far from mind.”

Despite the challenges creative nonfiction presents, Estriech found that, “in writing nonfiction prose about Laura, [he] wanted to be, in a small way, an agent of change.” Estreich goes on to say, “I wanted to raise questions about what “normal” meant, and to raise the question of who counts in our society. More specifically, I wanted to oppose a complex and singular portrait of Down Syndrome to the generic, medically ratified portrait that most people know.”

Estreich’s memoir has received attention from both the medical and literary fields. He has spoken and presented excerpts of the novel at the Willamette Valley Down Syndrome Association, the Spring Creek Conference on Nature and the Sacred, and the World Down Syndrome Conference in Vancouver. Estreich remarked: “I don’t know what effect Shape has had, but I hope it’s been positive. I do know that the responses to the book so far have been very gratifying, from other parents and from medical professionals. I’ve spoken to a number of medical audiences, and am always glad to have the chance to answer questions and have the necessary conversations. In general, I’ve found an extraordinary amount of goodwill, which reflects the goodwill Laura seems to inspire in person. This isn’t to say that attitudes don’t have a long way to go, about Down Syndrome or disability in general. But as a writer and a father, I’ve been very happy with the response to my book so far.”

The Shape of the Eye is a finalist in the 2012 Oregon Book Award for creative nonfiction and has been nominated for a Reader’s Choice Award (you can vote online for the memoir here). You can read an excerpt from Shape of the Eye and find out more information on George Estreich’s webpage.