Superstition Review is open to submissions for Issue 30! Our magazine is looking for art, fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. Read our guidelines and submit here.

The Online Literary Magazine at Arizona State University

Superstition Review is open to submissions for Issue 30! Our magazine is looking for art, fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. Read our guidelines and submit here.

Praise be to Encircle Publications for selecting my friend Muriel Nelson’s Please Hold as the winner of their 11th annual chapbook competition. Any and all lovers of poetry currently suffering frustration, blahs, even despair, over lineated topical prosaics may take heart. These twenty-five poems bind together actual poetry: musical-magic words. Deployed from within the courteous, indefatigably sunny suburban disposition I remember from my own childhood, they flick quirts & quips of vocabulary at the thorniest issues in Christianity’s crown: the suffering and death of innocents, ripping as usual through the here and now, while a good-enough god’s vital creation flourishes, for instance, its novel & ingeniously variable virus. Nelson (sometimes assisted by a stone-faced sidekick gargoyle) rubs dry sticks together, flint-striking among them worrisome sparks of prayer over nature, beloveds and the commons, such as they (and we) may seem-or-not to get along these days. Or ever? Organ of vox humana, ”That ultra-low purr,/ is it your scary business? Your pleasure?” (God Deafness).

Nelson’s work, full of noises and mouth feel, craves and rewards reading aloud: “words like worms wriggle out” (A Few Words from a Haystack with Facehole); “gold leaf down brown water, brown spot down gold leaf” (Up to You) as “radios amplify hubbubs” (Nap). “Rather than dazzle, please mail juncos”, a speaker requests. (You There). “Sanctus,” via violin, “rises/ over orange machines and trills through diesel” (Hold Sway). Wanton, irresistible frolicking language made of everyday diction we already know by heart.

Anxieties addressed in addition to pandemic include other illnesses and infirmities, clear air turbulence in aviation (Nelson’s own son the pilot at risk); hair overgrowing unruly in lockdown, nearby Mt. St. Helens’ volcanic eruption and forest fires, plus whatever else may fill in any of our blanks. Why is our local nit picked of the universe such a mess-in-plain-sight? Because this world of oops is God’s mirror-image shattered in a truck mishap. (Nap) Image-recognitions like this, more persuasive and quicker-to-the-pinch than rational proofs, are why/how we get to make sense of things, even as sense may go on to make and unmake the best efforts of artists, fans and rationalists. Because seeing is believing, the gardener –reluctantly conceding that god obviously prefers weeds– can’t really mind. Don’t look there. Look over here instead.

More ‘Notes’ than just one on hummingbird arithmetic would be nice: Vox humana, gargoyle, worm moon, clear air turbulence, retrograde, ankyloglossia, A440. I do like reading notes before I begin a book, getting that initial feel for what’s in store. And, what with everything zapping all around the world’s diverisities all the time, a particular writer’s cultural tropes are not so much common knowledge as used to be.

The sheer antic fun of Nelson’s wordplay, nimble, precise and outlandish enough never to get caught out in bourgeois complacency, wins us over and wins. Goofy poem “Hug,” for instance, declares its own title a word too ugly to be tolerated, and so (um, ‘embrace’?) substitutes (why not?) “waffle,” enumerating the latter’s superior fluff and sugary qualities and ending up (neverminding stiffly-posed ancestor portraits) in the very waffle that created us descendants. Or, “A woman with a hole in her brain the size of a lemon says”/ I find repetition soothing. Really?” The poem’s skeptical speaker attempts a few irritatant repetitions in rebuttal, but soon concedes the issue utterly.

Atheist Zweig engages these glories in awe for quite a while, as the music tickles and soothes. Gradually, though, an inner Richard Wilbur begins to notice the gigantic absence here of any human (and systemic) depravity in the world. If we can’t blame God (busy puttering light and music among the weeds), who gets held to account, and how? One poem, after ee cummings, seems to indict Mister Death, but this, sez I, is mere Manichaean heresy: did superpower Death create Itself? “Second Story Window” acknowledges a “God, who contours love with dark // who forsakes even Christ,” yet ends beguiled hearing bells and a shadow singing. In these poems music and wit (soothing, satisfying) never accuse. “Nap” comes closest: “God of great pain, lone, // self-bombing, bloody-crossed God… whom no one hugs, you untouchable, sharp, broken One.” Christianity, though, is obliged to address deliberate human sin— which the crucified god, (as we’re told by numerous authorities), forgives in advance and for all time. Wow! Thanks a bunch! Let’s sin again, maybe more so this time! Did I miss the parts where the moneybaggers get bounced out of the temple and barred from the heavenly kingdom even as some lumpy beast slicks through the needle’s eye?

Approaching the end, Please Hold arrives at “doting,” three times: a word I resist because doting is foolish. Am I supposed to be foolish for having indulged in delight among these poems? Must I, must other readers and Nelson herself, commit to holy foolery for Jesus and Saint Paul? After some research I reread “A woman with a hole in her brain the size of a lemon says” –increasingly my favorite. We cultured folk know perfectly well that art and all its witness entail willing suspension of disbelief; likely you and I can entertain Holy Foolishness without becoming wholly foolish. My atheistic smarts briefly snooze right over there, safe-&-sound.

Revisit the commodious mischief of this robocroon title, perpetrated, surely, by the gargoyle sidekick: Your prayer is very important to us. Our only-one god is busy hearing other supplicants and will respond to you in the order of your prayer received. You are currently number four trillion and eighty-two, please hold, or pray again later. (music) Organ, please hold that vox humana note. Dike against the sea, please hold; my place in the soup line; wall against the dark hordes, shutters against the storm, please hold. Hug me a little longer, (urgently/politely) don’t let go. Endure, don’t disintegrate, don’t die. And so on, let me count the ways. Please Hold your horses, your fire, your tongue, that thought, this book.

Please Hold, poems by Muriel Nelson, Encircle Publications, 2021, 28 pp.

Summer 2021 was a fruitful season for our past contributors! We’re back to announce another contributor’s new book: Anna B. Sutton’s poetry collection Savage Flower. Anna’s debut book includes “Postpartum,” which was featured in Issue 13. Savage Flower, winner of the 2019 St. Lawrence Book Award, centers on women in the American South. Reproductive rights, gender, religion, oppression, and family are just some of the timely and weighty topics brought up.

Make no mistake: the poems in Savage Flower will break you open with their beauty, with their unflinching ability to turn and keep the gaze on the moments of life so painful we try not to look at them: death and abandonment, injury and loss. Through Sutton’s work, we see the world as a continual process of loss and gain, of departure and return, in which “like prayer, waves fall back against the earth.” But these poems break you in a way that heals you, that continuously reminds you that despite its deaths and losses, this world still “[a] thing of beauty that / blossoms even as it withers.”

Emma Bolden, Author of House Is an Enigma

Savage Flower is available for purchase from Black Lawrence Press and Anna kindly mentions SR in the acknowledgements. Learn lots more about Anna and her work on her website and Twitter. Congratulations, Anna!

We are excited to share that past contributor Kasey Jueds is releasing a poetry collection, The Thicket, this November. Jueds’ poem “The Tool Shed” was featured in Issue 25. She is also the author of the poetry collection Keeper.

As its name suggests, The Thicket evokes themes of the natural world and poems often center on the less-prominent aspects of nature. Unique to this collection, the reader contends with an undefined force: it may be self, God, both, neither. Advance praise describes The Thicket as timely, serene, and observant.

Long after finishing The Thicket, I felt rocked inside its motion, a music made of wind and river current, blood, breath and wingbeat. In poem after poem Jueds leads us across the natural world, turned fabular by lavishly lyric detail, to passages unseen, through which deer spotted one moment vanish the next. The Thicket is a true beauty of a book, fully awake to the many spells of our existence.

Kathy Fagan, author of Sycamore

The Thicket will be available in November, 2021, from University of Pittsburgh Press. You can pre-order the collection from Pitt or Bookshop. Find more from Kasey on her website and Twitter. Congratulations, Kasey!

Brittney Corrigan is the author of the poetry collections Navigation, 40 Weeks, and most recently, Breaking, a chapbook responding to events in the news over the past several years. Daughters, a series of persona poems in the voices of daughters of various characters from folklore, mythology, and popular culture, is forthcoming from Airlie Press in September, 2021. Corrigan was raised in Colorado and has lived in Portland, Oregon for the past three decades, where she is an alumna and employee of Reed College. She is currently at work on her first short story collection and on a collection of poems about climate change and the Anthropocene age.

Brittney’s poem, “Whale Fall”, originally published in Thalia:

The ocean’s innumerable tiny mouths await the muffled impact like baby birds. Sediment clouds up at the deadened settling, and the flesh is set upon. How the weight of loss can be beautiful in its opening. Luminous worms undulate like party streamers as isopods and lobsters arrive to feast. This body holds an ecosystem unto itself: species found nowhere else but here, cleaved to the sunken remains. Sleeper sharks move in slow and gentle, ease the messy carcass to gleaming bones. And then, how the skeletal rafters of grief fuzz and bloom. How sometimes the coldest depths allow for such measured undoing. All the while hungry lives swarm and spread, come to stay. Limpets attach to the unhidden core. Sorrow in its abundance crushes, cycles, feeds. How the body rests, rich in what sustains.

Brittney’s poem, “Iteration”, originally published in Feral:

after the Aldabra rail One flightless bird evolves twice, before and after extinction. Collective bodies remember what it is to feel safe. You remember this, too. Before the world came lapping. A coral atoll—lagoon brimming with black-tipped sharks, no people—flourishes. Giant tortoises wander between turquoise worlds of sea and sky. The birds have no reason to fly away. A body with no enemies simplifies. There was a time when you didn’t need wings. Nothing is wasted. The birds push their long, ruddy necks through the coastal grass. Nothing chases them down. There was a time when you never looked behind you. The first time the ocean takes the island, every species on it goes extinct. A mass drowning. Thousands of years later, the water recedes. Fossils and sand surface; flora blooms. The bird’s white-throated cousins land on the shores. There was a time when your throat was open to the sky. The bird evolves again. Again relinquishes its wings. Again has no enemies. Again is a singular kind of being. You can do this, too. Sharks circle but can’t cross land. Bodies remold. Bodies wingless. Bones tell stories. Versions of stories. You recolonize your body. What it is to survive.

Brittney’s poem, “Rabbit, Rabbit, Rabbit”, originally published in The Wild Word:

The night a neighbor girl knocks on our door, baby rabbit in the bowl of her hands, I place it in a darkened box of straw, know it won’t make it to morning. My grandmother’s tradition for the first day of each month: stand at the edge of the bed upon waking, make a wish, yell Rabbit! Rabbit! Rabbit! and jump. Tiny rabbit body in my palm, soft and cold and still. Rabbit sitting on the moon, pestling herbs for the gods. A chant of white or grey rabbits to ward off smoke. The Black Rabbit of Inlé: his taking of this small life, his taking of my grandmother when I was still small. I must give this little un-rabbit back to the ground. Oh, to be so frightened that your heart cannot go on. But first, I must wake my young child. On this first of the month, I ease tangles separate through my hands. Sense something quivering just beneath what’s real as I leave the room. From down the hall, I hear the bedframe sigh. Little undone heart cupped in my hands. Little voice shouting a herd of rabbits onto the floorboards. I hop from foot to foot as they run past.

The following is an interview conducted on April 28, 2021, by Superstition Review‘s Poetry Editor, Carolina Quintero. It is in regards to Brittney’s works, writing process, and inspirations.

Carolina Quintero: Hello, Brittney! Thank you so much for agreeing to this interview with me. I really enjoyed reading your poetry. You have such a passion for animals and our environment and you put their importance into beautiful words. I also thought it was really striking and genius how you connect animal life to human life…Your writing frequently involves animals and the environment. What experiences or special interests have driven you to center your writing around this topic?

Brittney Corrigan: I’ve been drawn to animals and the natural world since I was a small child. I grew up in the gorgeous landscape of Colorado where my family spent a lot of time in the mountains and generally outdoors. And when I wasn’t playing outside or surrounded by a zoo’s worth of pets, I was watching episodes of Wild Kingdom. For years I wanted to become a marine biologist, drawn to the ocean and its creatures from my land-locked home. Though I’ve always felt connected with and protective of the environment, living in Oregon for the past three decades—with its wild coasts, wild animals, and wildfires—has strengthened that affinity and resolve. As the realities of climate change have made their way into my consciousness over the years—from my founding of an “environmental action club” in high school in the 1980s, to my love for the flora and fauna of the place where I live, to raising up my children in a world fraught with natural disasters and extinctions—I wanted to move toward action to preserve this planet and the life forms with which we share it, beginning with bringing awareness to these issues through my writing.

CQ: Your poems carry thorough knowledge about animals and ecosystems. What inspires you to learn about this?

BC: Voracious curiosity! I subscribe to countless email newsletters that showcase all things weird, wild, and wonderful (such as Atlas Obscura and National Geographic), and I love listening to podcasts of that ilk, as well (such as RadioLab and Ologies). I keep a running document of links to articles and oddities I find particularly fascinating that I come back to time and again to mine ideas for my work. In both my science-oriented poetry and my short fiction, the research is one of my favorite parts of the writing process. I love diving headlong into educating myself about a place or a species that I haven’t encountered before or that I just want to learn more about. In a high school English class, my teacher once presented me with a quote by Henry James: “Be one of the people on whom nothing is lost!” I carry that desire to notice, explore, and elucidate the world around me into my writing life.

CQ: What advocacy do you hope your poems will achieve? What audience do you hope your poems will reach?

BC: By bringing the plight of various ecosystems and species into my work, I hope to make what can seem like an overwhelming problem to tackle both particular and personal. I think if folks feel connected to the natural world and its creatures in specific, tangible ways, they will want to help and make change in small, meaningful ways. I hope that my poems reach folks of many interests, backgrounds, and generations and move them to learn more, and to do more, to combat climate change, extinction, and the effects of our current Anthropocene age.

CQ: What are your poetic influences as of late?

BC: My current favorite poets are Aimee Nezhukumatathil, Ada Limón, Ross Gay, Natalie Diaz, and Camille Dungy. I’m also enjoying reading essays on topics of extinction and the natural world by writers such as Michelle Nijhuis, Alison Hawthorne Deming, Elena Passarello, Linda Hogan, and Alexis Pauline Gumbs.

CQ: What advice would you give to young writers?

BC: I would say start with what you know and move outward toward your passions and ideas or topics you want to find out more about. First write for yourself, and then, when you are ready to share your writing with others, find your people. Seek out your fellow writers and readers with whom to share your work. Find a group of folks you trust and can share your roughest drafts with, and also find the mentors whose feedback will help your writing become stronger. And don’t be afraid to write outside of the boundaries you’ve been taught or the parameters you’ve been given. Break the rules and bust the genres open.

CQ: What are you currently working on in your writing?

BC: I recently completed a manuscript of poems about climate change, extinction, and the Anthropocene age. I’m now exploring those same topics in my first collection of short stories. As to poetry, I think science, ecology, and the natural world will always find their way into my work. I’m not sure exactly what’s next, but I’ve no doubt it will reveal itself to me, like bright animal eyes blinking out of the dark.

Join Superstition Review on congratulating past contributor Christopher Nelson on his new poetry collection, Blood Aria, out now. “In his powerful debut, Christopher Nelson examines the progenitors and forms of violence in the twenty-first century, from Cain and Abel to the damming of rivers. In everyday moments, spare poems depict pain with visceral sharpness, meditating on hate crimes against gay men, a father’s abuse of his son, and children murdered in their schools.” “There is loneliness in this poetry…but there is also redemption. We see glimpses of the speaker’s quest to find and know God, seeking answers everywhere, from Spanish cathedrals filled with holy relics to withered winter fields. The poems of Blood Aria ruminate on the sacrament of passing one day to the next, asking how much it matters what we believe.”

“In meditations ranging from a child’s incomprehension of a father’s violence to the suffering of those cast out for their sexual desires to the horror of mass shootings, the poems of Blood Aria pulse with an urgency that is both anguished and exalted. And transformative. To experience poems as passionate, as charged with wisdom as these is to enter into a kind of spiritual quest.”

Boyer Rickel, author of Remanence

To order your copy of Blood Aria click here. Also be sure to check out Christopher’s Twitter and website as well as his past work in Issue 15.

Join Superstition Review in congratulating past contributor Emily Banks on the publication of her poetry collection, Mother Water. Emily’s poetry collection covers a wide range of topics and emotions as well as features poems from her past work with Superstition Review, including “Poem for the Juvenile Cardinals” and “On the M15 Bus” from Issue 22.

Mother Water centers on maternal inheritance in literal and figurative forms. Through its water motif, the book traces the speaker’s transformations as she absorbs, and often resists, lessons from the women who guide her. The poems explore the speaker’s sense of self through feminine genealogy and her mother’s voice, the mother figure becoming simultaneously nurturing and threatening, teaching her daughter to survive in a perilous world. Coming-of-age poems are here, too, and poems exploring gender mystique, balance, relationship, and understanding. The book’s last section considers how we are altered by loss and how that alteration challenges our notions of both individual subjectivity and bodily autonomy.

University of Washington Press

Click here to order your own copy of Mother Water. Also, be sure to check out Emily’s website and Twitter as well as her past Guest Post.

Following is an interview conducted by Superstition Review‘s Poetry Editor, Erin Peters.

Jaclyn Youhana Garver is a freelance writer in Fort Wayne, Indiana. She writes fiction and poetry, and she has been featured in Narrow Road, Poets Reading the News, and Prometheus Dreaming (forthcoming). Her work has also been chosen by the Wick Poetry Center as a Traveling Stanza selection.

Jaclyn’s Poem:

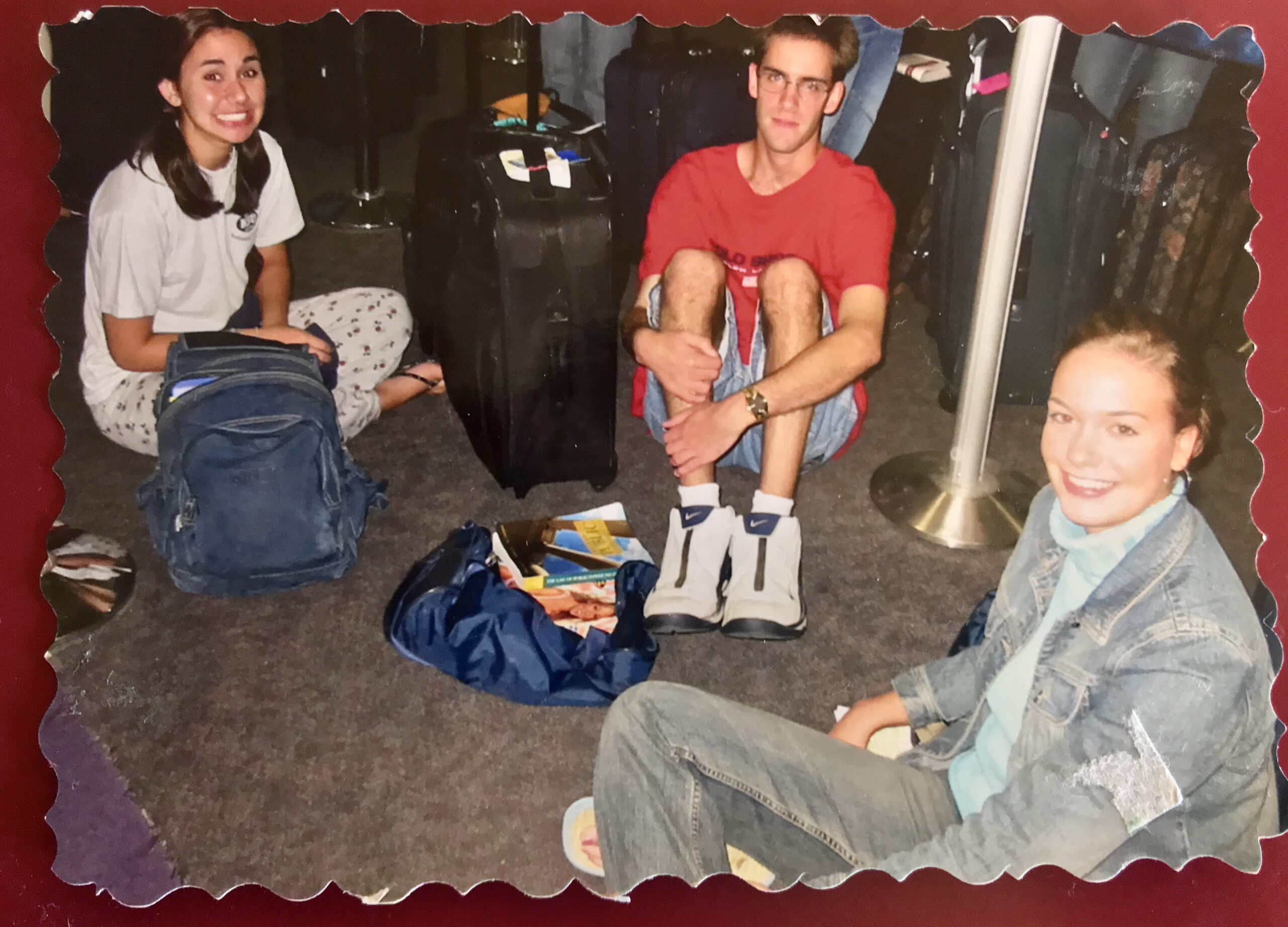

A COLLEGE GIRL MAKES WARDROBE DECISIONS BASED ON THE POSSIBILITY OF A RANDOM TSA SCREENING

1964

White kid gloves / cinched waist / her perched hat the

precise plum match to her two-piece suit / a corsage

(seriously, a goddamned corsage)

/ a Cherries in the Snow pout / a blushing visage

coral or rose / a fur, perhaps, in beaver or lamb.

2004

Pajama pants, peppered in cartoons / flip flops

with jewels that stud the thongs / pigtails

(seriously, goddamn pigtails)

/ a gray T-shirt that boasts,

“Journalists do it daily.”

Don’t look at me, Terry, standing in line. I know

you’ve a quota to meet, so many at random

searches to complete to assure you don’t permit on

the plane any drugs, bombs or hydrogen dioxide.

(Water, Terry, I’m talking about water.)

It doesn’t matter, though. You’ll search me nonetheless,

just like that agent last time and the agent who’ll be next.

And anyways, I’ll stick with PJs and pigtails, my sandwich

board to shout I’m threatening like sidewalk chalk, an eagle

scout, freckles, and winks, but apparently, the extra melanin

in my skin, a gift from my father, means you must pull me

from the line, away from my friends—none of whom you

also select at random, I see, goddamn it, Terry—so you

run the backs of your Caucasian hands along my Persian arms,

my cartooned inseam, my Assyrian torso. Then you make me move

my Iranian pigtails from my Middle Eastern shoulders.

You look so bored, Terry, and I wonder if you notice:

We’re quite the chatty portrait of our country tis of thee.

Interview With Jaclyn:

The setting of your poem is very specific and relatable for people who have travelled in American airports. What inspired you to write about the experience of a TSA screening?

This summer, I found a photo of myself at an airport in 2004, with two college friends, on the way to a Society of Professional Journalists conference in NYC. For the three or so years after 9/11, I began to be “randomly” searched on every flight I boarded. Seriously. Every flight. I thought it would help if I dressed in an unintimidating way. I remember I did this each time I flew, but it was wild to see photographic proof, especially compared to two other young adults who were dressed in, you know, normal airplane-appropriate clothing. Finding the photo, seeing how 21-year-old me felt like she had to dress, seriously pissed me off.

You’ve spent an impressive amount of time working for daily newspapers during your professional career. How do you feel this writing experience impacted you creatively?

I can’t even imagine writing creatively without my journalism experience. Writing for a daily newspaper made me completely deadline-focused. If a journalist doesn’t finish her story on time, there could an actual hole in the newspaper. Plus, the piece needs to be done well and accurately, often in hours or less—journalists don’t have days and days to perfect a piece of writing.

I adore the saying Done is better than perfect. Writers, especially creative writers, can get stuck in this I can’t show this to anyone because it’s not perfect hole. Then nothing ever gets finished. Writing for a daily newspaper was a wonderful way to keep from being too precious about my words. What I write matters, and it’s important to me, but once I turn in a story, it’s on to the next thing.

Writing for daily publication also gave me tough skin. I adore editor feedback and love seeing how subsequent drafts improve. Similarly, I also trust my gut. Writing is a wonderful mixture of both subjectivity and objectivity, even in poetry. My newspaper experience gave me an almost scientific approach to being creative.

What audience do you hope to reach through your poetry? Why is this audience meaningful to you?

As a reader, the best feeling is “Oh my goodness, you too? I thought I was the only one.” As a writer, then, that’s who I want to reach—anyone who has felt like me, to help them feel less alone. Strangely, the opposite is true, too: It’s such a rush to be told “I never thought of it in that way before.”

Those audiences are meaningful to me because it means we have a shared experience. Especially in 2020, feeling a connection—to anyone, even some writer you’ve never met—is vital.

How has the global pandemic impacted your creative process?

The pandemic hasn’t impacted my creative process so much as it’s impacted my creative output. I’ve written poetry since I was about 12 and I had a writing minor in college, so writing creatively has always been a part of my life. However, the pandemic made me itch to do more. I answered that by enrolling in a poetry class. The instructor helped me figure out what was missing from my poetry unlike any writing teacher I’ve had before. After the class, I asked where she was teaching next, and I signed up for that class, too. She helped me see where and how my work could be improved, which simultaneously showed me how to edit my own work.

This year has been hard, and there are a few things I can point to and say “That, specifically, made things a little easier.” Writing poetry is one of those things.

What is the most important piece of advice you have received as a writer?

In college, a journalism professor taught us to let the other person have the last say. When someone reaches out to a reporter to complain about something they wrote, the caller or emailer doesn’t actually care what the writer has to say about it. They just want to be heard (and maybe to be nasty). That knowledge, that someone who has something mean to say isn’t looking for a response, is incredibly freeing.

What are your upcoming projects?

I have a number of manuscripts in the works, but two are currently taking up the most of my time—a poetry book and a women’s fiction novel, which I will be pitching to agents early next year. I also write horror short stories. I love bouncing between genres and working on projects of varying lengths.

Following is an interview conducted by Superstition Review‘s Poetry Editor, Erin Peters.

Paul Chuks is an emerging Nigerian poet, writer and song writer, studying philosophy at the University of Benin, Edo state, Nigeria. He has appeared or is forthcoming in StreetCake Magazine, Kalahari Review, Neurological Magazine, Afritondo, The Remnant Archive and was recently shortlisted for The 49th Street‘s top ten poets in Nigeria. When Paul is not reading or writing songs, he’s critiquing the hiphop game or mimicking Michael Jackson.

Paul’s Poem:

To the Man Standing at the corner lifting the placard that said “All Lives Matter” as a protest against Black Lives Matter.

Your ancestors have apparelled in seem like bruteness in the past

But in this one, you are standing in a corner watching black lives evanesce like lights beholding a murky sky.

You think about justice, but your soul is

a leaky faucet, expelling your empathy

into an abysmal pit.

My ancestors’ tears are the ghosts of this poem/appearing as metaphors/telling you to drop that placard, go home & shut your mouth like Trump’s border[s]/because you are slow-dancing with the injustice of their history.

You are sipping our pain into a black-

hole/& our cries go out like a bird’s

tweet against a horrendous wind-

storm.

This poem is a scar tissue/like the body of a slave/telling the world/that blacks wouldn’t clamour for their lives to matter if there was fairness/as the world wouldn’t know dryness if there were no tongues.

Interview with Paul:

What motivated you to write your poem as a direct address? What impact do you hope this form will have on your audience?

I wrote the poem as a direct address, because many have allowed themselves to elude the important message of the movement, that is: take black lives seriously as you take others. When George Floyd’s sad situation happened, & the BLM movement kicked off to an almost untamable situation, many on the internet, sewed threads that ran counter to the BLM movement, with the prevalent theme: ALL LIVES MATTER. It irked me because they have not recognized that ALL LIVES MATTER remains a superstition, if a black boy can be shot at, because he reached into his car for his hair-brush, but the officer mistook it for a gun. And the jury acquits the officer on account that he tried to clamp down a druggie. ALL LIVES MATTER is a remark of the ignorant, or the devil, who enjoys the maltreatment of black people.

What has inspired you to write about the Black Lives Matter movement?

I think my biggest inspiration to write about the BLM movement, is the fact that I’m black. I have an ambition of taking a Masters course in America. The moment I get there, I’ll wear the profile of a black boy. I also write about them, because I can feel & perceive their pain. The Injustice makes all of us bleed from sealed places.

What audience do you hope to reach through your poetry? Why is this audience meaningful to you?

My poetry is intended to be variegated with everything possible to make a subject of, so i want the whole world to listen to me, while i play the game of painting pictures with words & inkling of my feeling(s). B: the audience is meaningful because without them, my tag as a poet is a facade. My pets can’t read, neither can the birds that perch on the trees behind my house.

How has the global pandemic impacted your creative process?

The pandemic has not affected my creative process, so far. Rather, my academic life. It has cancelled an academic year, pushing my future farther..all in this transient life.

What is the most important piece of advice you have received as a writer?

My best advice as a writer was gotten from another awesome writer I admire: Nome Patrick. He said: Paul, read more than you write. It was an interesting discussion on the essence of reading and the miracle it does to one’s repertoire. It has worked so far.

What are your upcoming projects?

More & more poetry. In fact, a chapbook is in sight. But for now, more poetry.

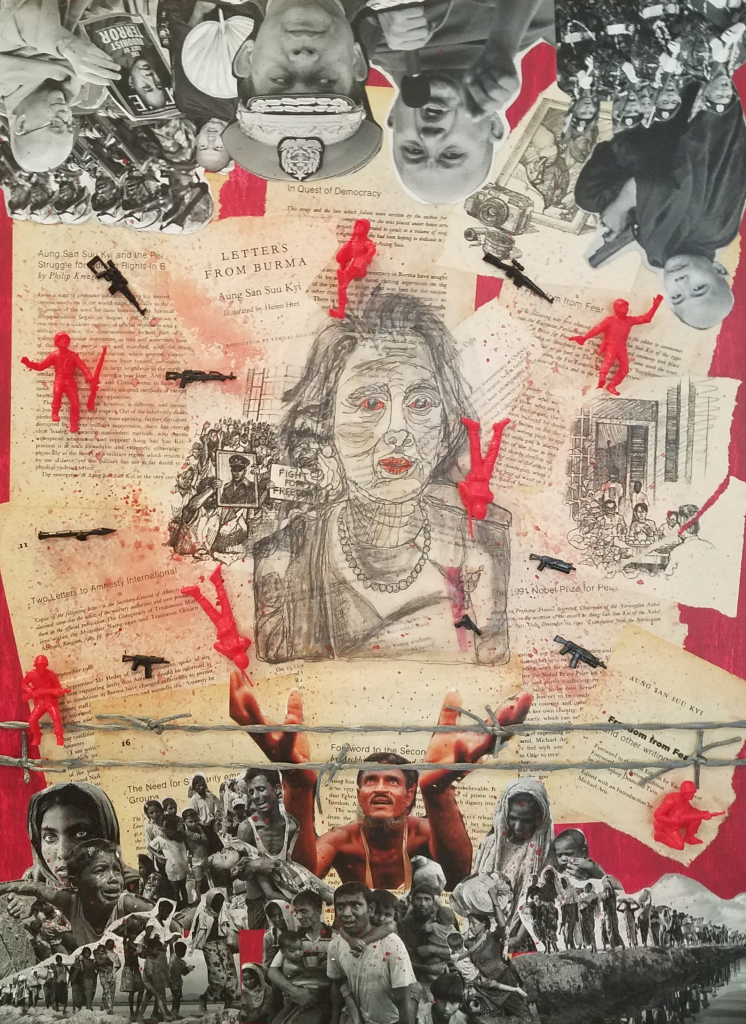

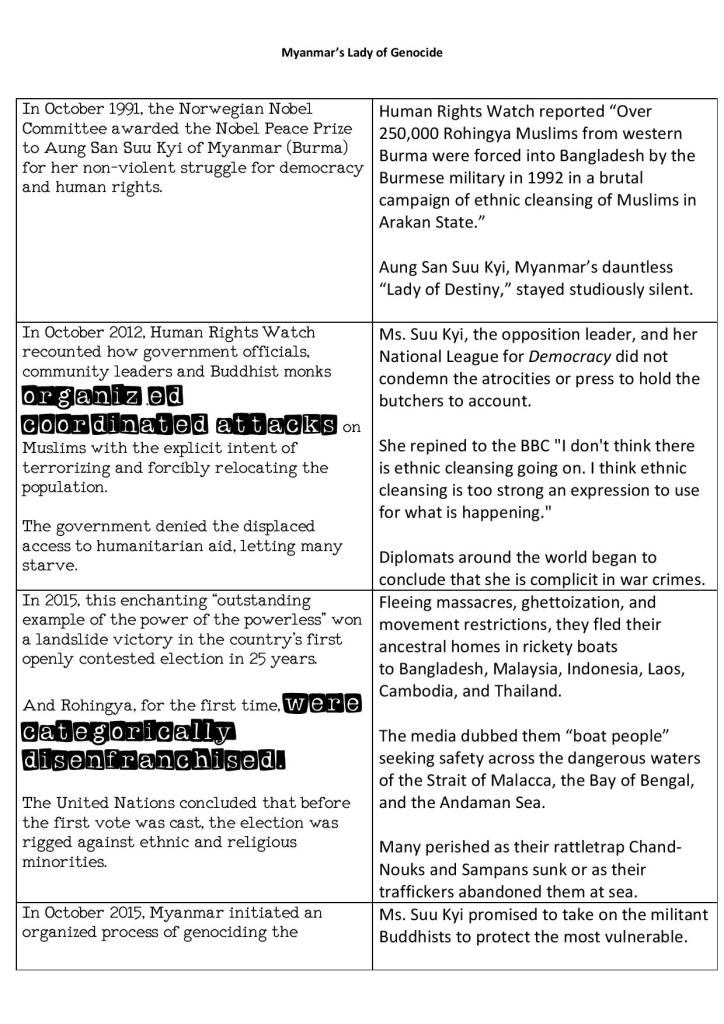

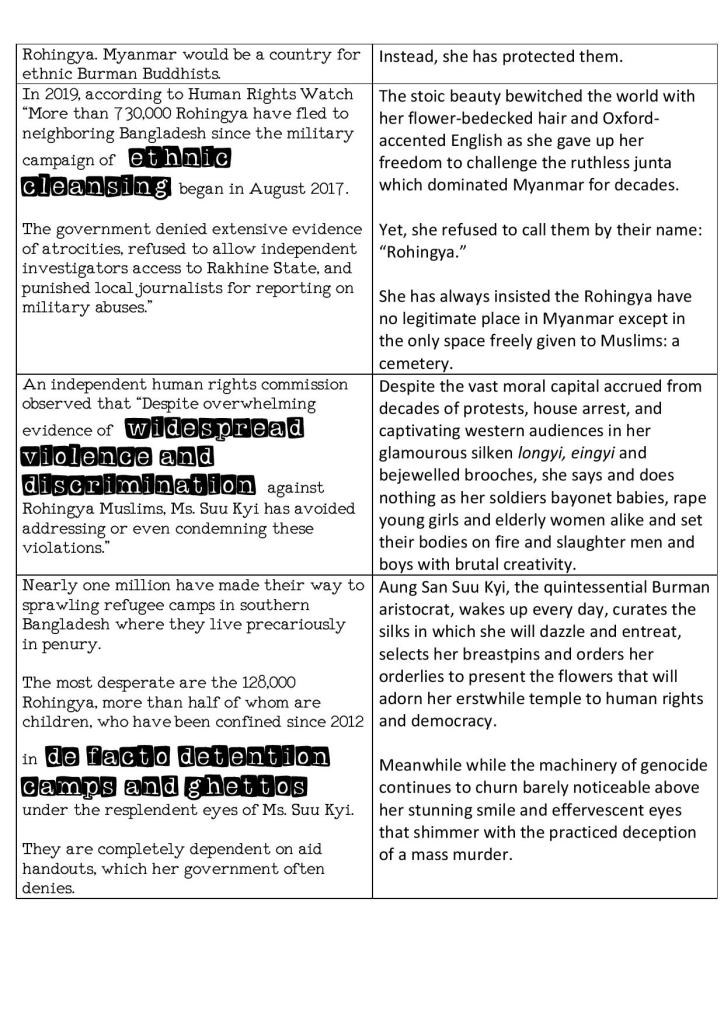

C. Christine Fair is a professor within the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University. She studies political and military events of South Asia and travels extensively throughout Asia and the Middle East. Her books include In Their Own Words: Understanding the Lashkar-e-Tayyaba (OUP 2019); Fighting to the End: The Pakistan Army’s Way of War (OUP, 2014); and Cuisines of the Axis of Evil and Other Irritating States (Globe Pequot, 2008). Her forthcoming book is Lines of Control:

Lashkar-e-Tayyaba’s Militant Piety, with Saifina Ustad (Oxford University Press, 2020). She has published creative pieces in The Bark, The Dime Show Review, Clementine Unbound, Awakenings, Fifty Word Stories, The Drabble, Sandy River Review, Sonder Midwest, Black Horse Magazine, Furious Gazelle, Hyptertext, Barzakh Magazine and Bluntly Magazine among others. Her visual poetry has appeared in Awakenings, pulpMAG and several forthcoming pieces in Abstract: Contemporary

Expressions, The Indianapolis Review, Typehouse Literary Magazine and PCC Inscape Magazine. She causes trouble in multiple languages.

In this interview, Fair explores her experiences with art in the world of science, and she explains her process of developing her work centered around Aung San Suu Kyi, Myanmar’s State Counsellor.

You can find C. Christine Fair here on Twitter, here on Facebook, at at her website here.