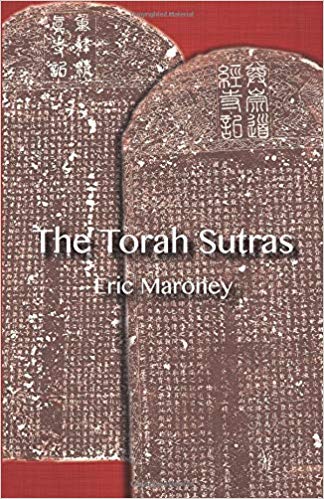

“Rabbi Meir said, anyone who engages in Torah study for its own sake (‘lishma’) merits many things”

“Rabbi Meir said, anyone who engages in Torah study for its own sake (‘lishma’) merits many things”

We are always torn apart. Behind the face we present to the world, there is a fracture. Two rudiments in our nature spar: the craving for control, and the dread of disorder. These opposing states, so closely linked, cause us no small misery, but the dynamic is so much a part of our ingrained habit of thinking that we constantly try, though with little success, to smother it with all manner of distractions.

We frequently wake up early in the morning with a crashing, dawn-clarity in the form of the question: What can I do about some awful problem? What we are really asking above and behind this question, is “can this problem be contained or controlled?” And if not – if the problem can’t be mended – how do we live with our sense that by not resolving this difficulty, and by allowing it to stand shamelessly unresolved, life’s great promise of joy will unravel from its spool? Further refined, we can distill the question to its rock hard core: How do I live with pain, grief, anguish?

We have all encountered such moments. But nothing distresses the quest for control more than a crisis of health. The body lurks, waiting; it conceals sickness under skin, tissue and bone. Beneath the veil of our physical stability, a system bubbles toward disorder. My own crock boiled over when I was twenty-nine and diagnosed with cancer. At a time of life when people typically view mortality though a long lens, my death seemed more immediate. I had no resources to deal with the reality of death: therefore my responses were limited. My mind contracted under the idea of death. My notions were hedged by binary postures: fight, win, move on, or fight, lose, die.

Pressed in this vice, I ultimately found it most reassuring to learn to abandon the notion of continued life. This brought a measure of peace. Death is the ultimate negation – a blunt, inescapable fact. Somewhere on a cosmic script, the conclusion is written in indelible ink: you will die. So by embracing death, by laying down at its feet, I let go of the struggle against its oppressive strain. I was still bound to life, to be certain, but only by sheer threads.

In the first few years after surgeries and treatments, I devalued existence. This attitude worked under a certain set of narrow conditions. But as I expanded my horizons after the disease, this stance evolved into a crisis of conscience. How can we live without embracing life? Clinging to death is a poor long term-solution, for even after the cancer was in remission, there was still the fact that I might die at any moment. Death simmers inside of us. My unbending cheapening of life did not solve the problem of death – it merely postponed it. I had driven myself to the verge of an existential cliff. In order to continue to live, I had to change the mental formula that had been useful since I was diagnosed with cancer – because the thin gruel of indifference to life cannot sustain a flea.

If we face suffering, sickness, depression and death, we can turn to something well beyond us: religion. In the years following a great crisis, I turned to Judaism. But my reason for this move, I believe, veers very far from the common expectation. Religion did not provide me comfort. A Jewish life did not offer me hope of a healthy body as a reward for my virtuous actions, or the recompense of an enchanted afterlife beyond a bodily existence marked by pain and suffering; nor did I seek the protection of a powerful and providential deity who could answer my prayers.

On the contrary, Jewish practice catapulted me beyond the bounds of reward and punishment to a real “space” where my deeds are free from the expectation of reward. This is a crucial point: by practicing Judaism, I can relinquish control to the realm of pure Jewish action. In the language of Judaism I perform the mitzvoth, the Jewish religious requirements, not for any payoff, but, as is said in Hebrew lishma, for and in themselves. This perspective has steered my apathy and indifference into more disciplined channels.

I practice Judaism to practice it. This sounds like an echo, but the seeds of this practice produce sturdy foliage. With Jewish ritual practice detached from reward, I can pursue a goal without the restraints of expectation. My mind and heart practice Judaism’s ritual demands with detachment. Detachment, of course, has pejorative implications – a lack of caring, a stance of aloofness – but it can also emancipate; and in a paradoxical turn, the freedom of detachment can transform our indifference into a more vital, lasting form of care. And the practice of lishma, of doing a deed in and for itself, can be exercised everywhere. By living life lishma, the mind is freed from the stark habit of thinking that the two rudiments in our nature spar: the craving for control and the dread of disorder.

In lishma, we transcend the need to control the events of our lives. Order happens, disorder happens – they are states that come and go and we have no control over either. But no matter what happens, we perform our duty and live life. Our imperative to action is action itself. With patience and practice, even life’s gravest challenges and abrupt transformations become shaded in different hues. Events take on the color of the moment, rather than the stain of our anxiety for specious stability. When we are no longer distracted about the issue of control, we are able to free ourselves from the slavery of expectations. And by doing so, we are able to see ourselves in the light of the singular, precious instant.

Today we are pleased to feature Kate Lechler as our Authors Talk series contributor. Kate discusses her essay, “The Breathtaking Sting of the Pull,” and what non-fiction offers to her as a writer.

Today we are pleased to feature Kate Lechler as our Authors Talk series contributor. Kate discusses her essay, “The Breathtaking Sting of the Pull,” and what non-fiction offers to her as a writer. Today we are pleased to feature poet Rose Knapp as our Authors Talk series contributor. Rose talks about how her poems deal with language and translation.

Today we are pleased to feature poet Rose Knapp as our Authors Talk series contributor. Rose talks about how her poems deal with language and translation.

Wednesday, February 24th from 12pm-1pm, ASU instructor Lori Eshleman (College of Letters and Sciences) will be giving a book discussion on her novel

Wednesday, February 24th from 12pm-1pm, ASU instructor Lori Eshleman (College of Letters and Sciences) will be giving a book discussion on her novel