Thanks and Ponies: The Art of Acknowledgment

I am that reader who devours every word between the covers of a book—the dedication, preface, prologue, epilogue, notes, and everything in between. I even pay attention to the copyright page, like the one in Justin Cronin’s The Passage that catalogues the novel under the subjects Vampire-Fiction, Human experimentation in medicine-Fiction, and Virus diseases-Fiction, story clues that not even the book jacket copy gives away.

I am that reader who devours every word between the covers of a book—the dedication, preface, prologue, epilogue, notes, and everything in between. I even pay attention to the copyright page, like the one in Justin Cronin’s The Passage that catalogues the novel under the subjects Vampire-Fiction, Human experimentation in medicine-Fiction, and Virus diseases-Fiction, story clues that not even the book jacket copy gives away.

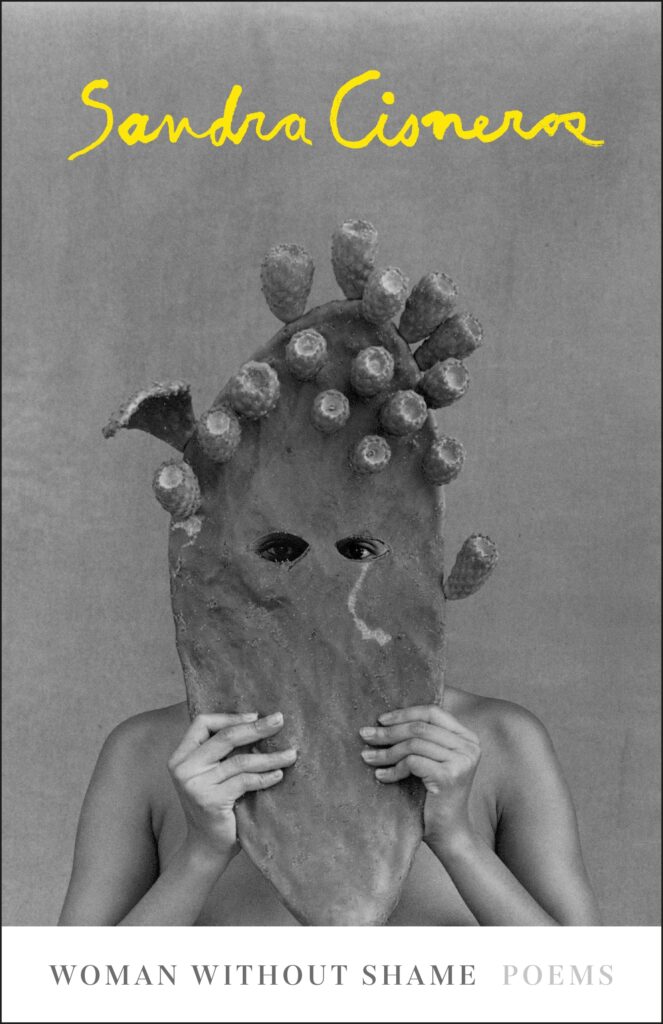

I especially enjoy reading the acknowledgements. While every other part of the book ultimately belongs to the reader, an author’s acknowledgments offer a glimpse into her own life. Who or what we acknowledge reveals what we value in writing and life. Who does the author recognize, care about, appreciate? Does she thank family, friends, mentors? (Most everyone does.) A place of employment? (Only if they provided time or money for the writing project.) Sorority sisters with spare couches? (Angela Flournoy). La Virgen de Guadalupe Tonantzin? (Sandra Cisneros). What about the person who bought the writer his first dictionary? (Junot Diaz scores big points with me here.)

I’ve been named in book acknowledgements, and it’s usually an unexpected honor from a former student or a writer whose manuscript I read, someone who wants to remind me I’m a small part of their work, a member of their tribe. Now that my short story collection approaches its publication date and it’s my turn to appreciate the village it takes to bring a book to a reader’s hands, I’m terrified I’ll forget someone I’m expected to thank, like when Oscar winners ramble the names of everyone from their director to their barista but forget to mention a long-suffering spouse. Alanis Morissette, in her song “Thank You,” takes an even wider view, recognizing everything from India, a country of over a billion people, to more abstract concepts like disillusionment.

But an acknowledgments page has a specific purpose: to give recognition to whomever or whatever supports the writing and production of a book. That narrows it down some. India has no role in my story collection and needs no thanks, and I don’t always appreciate my moments of disillusionment. Still, give credit where it’s due. Writers don’t create books alone. Sure, the actual act of writing is solitary. You alone plant your butt in a chair, turn on a computer, open your document, and conjure words. You pace the floor and cry on your own, and you alone decide to push past the urge to play Candy Crush or Pokemon Go. When you fail, which every writer does, over and over, you do that all on your own too.

But you never succeed on your own, as the very custom of acknowledgment reminds us. Every writer who keeps sitting in that chair depends on the invisible community of people carried into the writing space. Maybe it’s the teacher who taught you how to “nibble the pig” so your project seems less daunting (thanks, Ron Carlson, for all those years I kept a picture of a roast pig on a platter above my computer to remind me it was only possible to eat that thing one bite at a time). Or the relative who bought you books every birthday. Or the small town you thought you hated and wanted to leave, while the people there hang on in your mind, populating your pages.

The acknowledgments page is where writers honor the people and places that nurtured and mentored them. Writers frequently mention professors, workshop members, even the program administrators who made their MFA years easier. Junot Diaz, in four pages of acknowledgments in The Brief, Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, goes well beyond that, thanking his many clans and the people who “bought me my first dictionary and signed me up for the Science Fiction Book Club” and also “Every teacher who gave me kindness, every librarian who gave me books.”

Acknowledgments also credit those people who provide whatever the writer needs to shape a book and usher it into the world, everyone from trusted friends who read and comment on drafts to agents, editors, designers and publicists. And I discovered in a quick survey of books in my personal library that those people deserve not only gratitude, but small horses. Justin Cronin offers “thanks and ponies” to his supporters, and Jenny Offill promises her “crackerjack editorial, publicity, and production staff at Knopf”: “I owe each and every one of you a pony.”

Some writers share gratitude specific to a book’s content. Margaret Atwood, in Oryx and Crake, thanks the people from whose balcony she saw “that rare bird, the Red-necked Crake,” and Alice Munro’s acknowledgements for the collection Too Much Happiness focuses solely on the people and books that led to her discovery of Sophia Kovalevsky, subject of the title story.

Nearly every author saves their final thanks for those intimates who, as Margaret Atwood describes her husband, Graeme Gibson, “understand[s] the obsessiveness of the writer.” No surprise there, as those are the people who respect your closed door, nurse you through every “art attack,” and celebrate those small victories peculiar to writers, like a “good” rejection note. They deserve public recognition and your private appreciation—every day.

My acknowledgments page is already with my publisher. I still have a small window of time to add names. But really I think of those acknowledgments as formalizing what the people who support me—or any writer—should already know and feel, whether it’s between the covers of a book or not: their value exceeds what mere words can say.

Thanks. Just thanks. (But no ponies—they really don’t make good gifts.)