I’m always buoyed and a little surprised when I get an email from a reader. Of course I write to be read, but even so, this proof that someone I’ve never met has read something of mine and taken the time to respond is always a little stunning. So when I saw the email that said, “Loving Rachel” I opened it eagerly.

I’m always buoyed and a little surprised when I get an email from a reader. Of course I write to be read, but even so, this proof that someone I’ve never met has read something of mine and taken the time to respond is always a little stunning. So when I saw the email that said, “Loving Rachel” I opened it eagerly.

There was no greeting. Only this: “I just finished reading your book Loving Rachel. I am left with so many questions and I just have to know… Did Rachel grow up to be a beautiful woman leading the life that everyone leads?

Or did Rae-Rae forever stay …”a problem.” I must know the answer. For you see, I also have a Rachel…” The letter went on, every sentence heartbreaking and familiar.

I got up from my computer, boiled water for tea. The question followed me into the kitchen. “Did Rachel grow up to be a beautiful woman leading the life that everyone leads?” How could I respond?

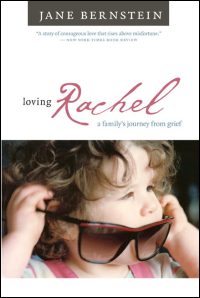

Loving Rachel, the book this woman read, tells the story of my family after my younger daughter was diagnosed with an uncommon disorder called optic nerve hypoplasia. Rachel was six weeks old when my husband and I were told she would be blind. Two weeks would pass before we found out that other “associated disorders” often appeared with ONH. Along with low vision or blindness children also had seizures and “intellectual impairment.”

This was in 1983 when I was married, and had a four-year-old daughter. I was a fiction writer and had no interest or inclination in writing about this difficult period following the diagnosis, when we waited to find out which, if any, of these disorders Rachel might have. I didn’t want to write a book about Rachel, but I wanted badly to find one, to find stories about other families who had a baby with disabilities.

Because this was an era before the internet and before the boom in memoirs, I had only the library in the town where I lived, and the only family stories I found were saccharine, uplifting tales, in which the first tumultuous days after a devastating diagnosis were a blur, and all the parents seemed to wipe their tears and find their baby was a gift from God, brought to earth to teach them the meaning of love. I was distressed by these books, felt trapped between feeling that these compressed, sanitized stories were false, and feeling maybe they were true for everyone else for me.

When my agent first asked if I’d consider writing a nonfiction book about Rachel’s birth and its effect on my family, I said no. The only nonfiction I’d written was dry and academic. I didn’t think I knew how to do it. What changed my mind was this memory of pouring over books in the town library, looking for a story that might help me make sense of my own.

I knew I wanted to describe those first hours after the initial diagnosis, to write about waking the next morning, about trying not cry in front of my four-year old. And I did that. Although Loving Rachel ends when Rachel is three, most of the book is centered on that first trying year.

My editor was at a trade publisher, which released and utterly ignored the book. Somehow, miraculously, readers managed to find it, parents, like the mother who’d just written, like me, who had new babies, and had heard scary diagnoses, and could not in any way imagine what kind of life their lovely babies might have. Over the years, I gave occasional talks and once in a while I got notes from readers, many of whom also wrote, “I also have a Rachel…” But no reader ever asked: “Did Rachel grow up to be a beautiful woman leading the life that everyone leads? Or did Rae-Rae forever stay … “a problem.” No reader ever wrote, “although I love my baby more than anything in the world, I wish she were dead.”

I knew I had to answer. Her letter reminded me how desperate I was after Rachel’s diagnosis. What could I tell her about our life since those early days?

I could sidestep completely and remind her that ONH was the result of an “accident in development,” and not a disorder in which every child had the same disabilities. When Rachel was still an infant, I met a teenager with ONH: she was completely blind, her seizures were poorly controlled, and she was cognitively intact. I came home weeping, not yet knowing that my own daughter would grow up to have usable vision and seizures that would be well-controlled, but would never read, write, or live independently, and that none of these disabilities would be as challenging as the behavior problems that made her life and mine so difficult. Still, it seemed unhelpful to say, “who knows how your daughter will be when she grows up,” when I could feel this stranger’s yearning for answers.

Rachel is thirty years old. When I ask myself the question posed by this young mother, I want to shout, Yes! Her life is really good. It’s just that you can’t imagine it. You really cannot imagine, I want to say.

Every detail necessary to explain how well Rachel is doing would provoke tears. Anything but that! she might think, as I did, shortly after Rachel’s diagnosis, when I thought: blindness, okay, I can work with that, but … mental retardation? I could not yet hear those words (and those were the words then used), could not imagining raising a child with mental retardation.

Did Rachel grow up to be a beautiful woman leading the life that everyone leads? Well, yes, she is a beautiful woman, and everyone’s life is different.

To describe Rachel’s life means I must write about our long quest to get her into a “Community Living Arrangement,” where she now lives with two roommates and 24-hour staff. It means explaining how successful Rachel is at her job, at a worksite (what used to be called a “sheltered workshop,”) where she does packaging and assembly work.

You cannot imagine, I think.

It’s hard to describe, I want to write, (and surely this was true, since trying to say something about Rachel and our years together has taken two books and a dozen essays and I’m still not done.

The years did not pass in a blur. It’s just that there have been too many years for me to say in a sentence or two what it was like, being Rachel’s mother. The wrenching days that follow a diagnosis are just a blip. I cannot tell her this, of course. She will wipe her tears soon enough and accommodate to her baby. Before she knows it, whatever her baby’s abilities and disabilities, she will be busy searching for the best therapies, for preschool, for recreational opportunities, since life for so many children with disabilities is lonely, without access to playmates, appropriate toys, without good play skills. For families with a child with disabilities, dependent care doesn’t fade after a few years, it’s ongoing, decade after decade. There’s hardly time for tears when you have to find “staff,” train them, trust them, lose them when they leave for other jobs or graduate from school, find someone new to train and trust. There’s no time for tears, when those “covered” hours are so precious, so necessary, as they were for me, saved for the most pressing activities and cannot be squandered on hanging out with friends or reading a book.

I could tell her to beware, since services for children with disabilities are fine until the child turns 21, at which point, all entitlements end, and how this is a much more wrenching time of life, harder, more taxing, more frightening, than the soft, poignant, seemingly unbearable grief we feel as young parents.

The years didn’t pass in a blur. They were long and hard, and there were many times when I would count how many years had to pass before Rachel could possibly move, and facing the thousands of days still ahead, I’d think, I’ll be half dead by then!

I didn’t die. Rachel moved in 2005. The year she left, every morning, I would walk the dog and think: I am just walking the dog, amazing by the tranquil morning and the way time stretched out. When Rachel moved, her life blossomed and so did mine.

Maybe I write books because I can’t compress. I can’t bring myself to respond to this email with a truism, to whitewash, to pack all the complexities into one simple sentence. There is no way to explain to this mother that Rachel is a beautiful young woman leading a life that makes sense for her. Rachel’s life, my life — a long time will pass before she understands.

- Guest Post, Jane Bernstein: The Museum Course - November 19, 2016

- Guest Post, Jane Bernstein: Loving Rachel - April 6, 2014

Stunning. Thank you for this, Jane.

Amazing. It’s nowhere near as terrible a diagnoses, but I do wonder if this is somewhat like how my mother must have felt when I was diagnosed with juvenile arthritis at four-years-old. I remember those early years being filled with missing school for doctor’s appointments at least once a month, trying new medications, different and sometimes painful physical therapies. I can’t even imagine how a parent must feel watching their kid go through the aftermath of a life-long diagnoses of any kind. And I think it’s wonderful you choose to answer that sender’s question because you were once in the same position. Thank you.