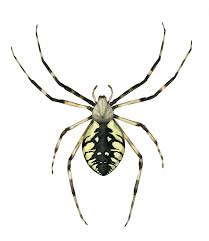

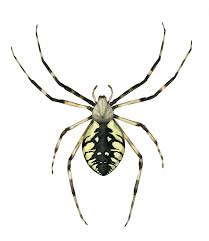

In July, just outside the back door at elbow height, I discovered an orb weaver, Argiope aurantia, growing more and more enormous each week, clinging to its web. The pattern of its weaving was mostly invisible except for one thick white zigzag down the web’s vertical axis. Each time I opened the door, the whole edifice swayed and swung. The spider hung in wait.

In July, just outside the back door at elbow height, I discovered an orb weaver, Argiope aurantia, growing more and more enormous each week, clinging to its web. The pattern of its weaving was mostly invisible except for one thick white zigzag down the web’s vertical axis. Each time I opened the door, the whole edifice swayed and swung. The spider hung in wait.

A bestiary I found on the plush seat of a chair in a used bookstore in August opened naturally to a full-page photograph of this very spider, as if the book had been placed there, marked for me. Aha, I thought. Now I’ll know what it is and whether I should be afraid. The book, however, was written in Spanish and so I noted araña tejedora and came home to look up the second word, not a cognate like the arachnid that I imagine poses in araña. The search engine brought back “weaving machine,” “loom” when I typed in tejedora. Where I had hoped for clarity, I found only the obvious. So, it must be its beauty and the peach-pit size of its body, its long striped legs, I decided, that rate a whole page in full color. But once I knew its Spanish name, I had other questions: How long would it last, protected under the roof of the porch? Would it go before I needed the rake and snow shovel, their handles bound with spider silk to make one pillar holding up the web?

Then, September sun began to brighten lawns with its slight touch of yellow. Crickets increased their volume. I watched from my chair a patch where leaf shadow flickered through the doomed leaves of a pin oak. That moving light fanned from chair legs to table legs, disappeared soon, and on the loom of days autumn came on.

*

I discovered the spider has other names: garden spider, corn spider, writing spider, the one who reweaves her web, or at least the zigzag, every night. I noticed in mid-October as nights began to cool that she was a bit off-center in her web and found myself thinking that her death must be near, caught myself, made sure I didn’t wish it, having known her so long. A day or two later, I found the web empty. I worried she had tried to get into my warm house, so I glanced at my feet and the rugs on both sides of the door. I looked for her under the web on the porch step. Finally, I looked up and found her body hanging high over the web, legs bent toward her huge torso. It was near freezing the night before. I wondered if she is built only for summer, her fragile mechanism like a watch’s once-wound gears. I don’t know how she lived, and then I needed some explanation of how she died.

*

A naturalist would have more to say than genus and species, scrupulous research standing in where I have only this willingness to look, and a list of mysteries:

Did I watch because I recognized the spider or her labor? Did I covet her design because I strain to find my own? Or did I envy the sharpness of her zigzag, that she could resay it every night, whiter, cleaner, clearer each time, and that saying it seemed to make her bigger and more powerful each day?

What do I know about the spider? Only my response to her, my fascination and desire to see up against my side-eye fear of looking too close. I know this: scale is part of my bafflement – I could never get small enough or close enough to understand or feel how it is to be her. And part of this puzzle is my revulsion when I leaned in to see. I loved her web more than I love her? No. I loved them both – but I was able to see web and zigzag in ways I could not see the spider.

*

The day after I mourned her empty web, I wrote: The spider awakes! As the day warmed, I watched her flex one or two of her folded legs, then another two or three. By dusk, she was back at the center of her web, gathering her silken glamor. I tried to lean closer to memorize her shape before the frost, but her size and grasp made something tickle at the back of my throat.

*

November, and the spider’s egg sac hangs like a plum from the porch roof. She spent her last days suspended near it, abandoning the summer web, its white line tattered and blurred. Each day of her death I opened the door slowly, looked for her before stepping out, watched as each cold night left her smaller, long legs folding closer to her body.

I read that her nearly violet brown sac could contain up to a thousand offspring. The females will emerge in spring looking just like her, only much tinier, and will grow a leg-span almost as wide as my hand over a summer, carrying the knowledge of web and weave in their impossibly expendable bodies. If they survive, every night they will remake like their mother from the substance of their spider selves a thick white line in even stitches, and when it’s time, they will construct the fruit-shaped sac to shelter their eggs.

*

A web yawns wide as out-flung arms. An egg sac keeps its secrets, dangling purse holding everything she spent.

Across the room, the little thrift shop Royal I bought for its sleek silver chrome despite its broken mechanism catches on its fancy keys a glint of sun as it rises. A naturalist would remind us that it is we who descend, our dangling pod turning out here, fixed to the star.

*

I did not rescue her body after it fell, after it lost its beauty and symmetry and became simply fearful. I cannot make my home out of the elements of my body as the spider taught. I use my house, solid uninspired stucco and plaster, to shelter the meander of my thoughts, the pattern I make with my notebooks and the flexible net of intention. She is gone now, blown away or crushed to dust. I keep vigil by marking off each writing day of oncoming winter, holding close with these stitches the seethe and foment of life inside.

Each Tuesday we feature audio or video of an SR Contributor reading their work. Today we’re proud to feature a podcast by Joe Neal.

Each Tuesday we feature audio or video of an SR Contributor reading their work. Today we’re proud to feature a podcast by Joe Neal.