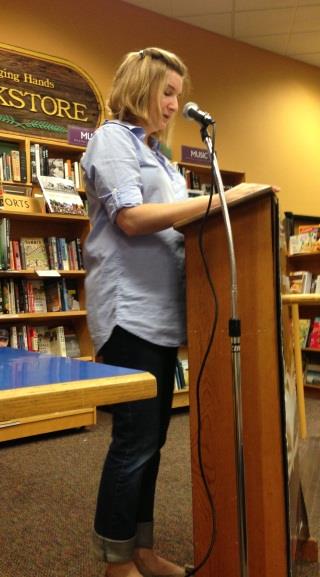

Last month I had the honor of attending a reading at Changing Hands Bookstore with Jamie Quatro. Although I had already finished her entire collection, hearing Jamie read her work was beyond captivating. The energy with which she spoke exemplified the dedication and passion she has for words—using them to create a rhythm and molding them into complex stories. Jamie graciously agreed to do this interview regarding her debut collection, I Want to Show You More, via email.

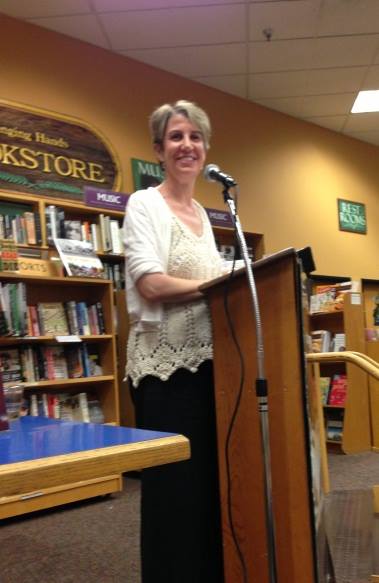

Superstition Review: At the Changing Hands reading you invited author Melissa Pritchard—one of your professors from ASU—to join you. How has your relationship with Melissa contributed to the literary aesthetic that you have today?

Jamie Quatro: I enrolled in Melissa’s MFA workshop with a BA from Pepperdine and an MA from the College of William and Mary, both in English. When I met Melissa, I was a Princeton PhD dropout and mother of four children under the age of eight. I was writing stories at night, after they were all in bed. I didn’t know if the stories were any good. I had no idea how to edit myself, or how to submit to journals. So I was lucky to land in Melissa’s workshop—I can’t imagine a more supportive teacher. Melissa’s emphases on social responsibility and spirituality meshed with my own aesthetic concerns. And she introduced me to the work of two poets I now call favorites: Jack Gilbert and W.S. Merwin.

S[r]: Many of the stories in your new collection deal with acts of infidelity—where your character never actually crosses a physical boundary. What is it about this type of affair that compelled you to explore it so deeply?

JQ: There’s something inherently erotic about the “almost” in fiction – one can let the imagination take over when the person or thing desired is at a physical remove. To me, erotic urgency in fiction (and in life) resides not in the act itself, but in the build-up. And the longer the space between suggestion and consummation (which fulfills, but also kills, to some degree, the original desire), the more charged the prose becomes. So when a fictional affair carries the suggestion of fulfillment but is, in a physical sense, impossible to consummate, it creates a kind of electrical current on the page. When I was drafting, I found this urgency creatively propulsive. At one point, I did draft a story where my characters actually went through with the proposed meeting at Grand Central—they found the empty car, boarded the train, etc. But in the end, I decided it was best to keep them in the place of not-quite.

S[r]: I came across this Book Notes piece you wrote in largehearted boy discussing the music playlist for your collection. Your stories have a distinct lyrical cadence that drives them forward. Can you expand on the role of music in your own writing process?

JQ: My mother is a concert pianist. Growing up, I’d fall asleep listening to her practice some of the most gorgeous and difficult music ever composed: Liszt’s La Campanella, Chopin’s Premiere Ballade. I grew to know those pieces intimately—the phrasing, dynamics, etc. When the piano stopped—if I was still awake—I’d keep the music going in my head by changing the notes into words. I didn’t realize I was doing it; the words seemed to originate in the piano. My stories often come in a similar fashion: they begin with sound or cadence, a pulse or rhythm to which I begin to attach words.

S[r]: “Ladies and Gentleman of the Pavement” took me to a place I have never been. Obviously it is an alternate reality, but on another level it deals with complex ideas including (but not limited to) resistance and redemption. Where did the idea for this intricate story come from?

JQ: I saw an image online, a distance race somewhere in Europe in which the competitors had giant crucifixes strapped to their backs. The image haunted me. Why? What was the point? If I were going to strap something to my back during a race, what would it be? It’s anyone’s guess how I wound up with phallic statues. Thank goodness there are also objects d’art bobbing around in the runners’ moisture-wicking carriers.

S[r]: In an interview with The Center for Fiction you mentioned that you weren’t thinking about a book until most of the stories were finished; yet there is a strong momentum between your stories. Can you describe the process of selecting these stories and arranging them in the order they are in now? Was that a simple or difficult task?

JQ: I agonized over the story order. I had these self-imposed parameters: start with a flash piece, to hook readers quickly and “break them in” to the voice; disrupt the expected narrative order in the linked stories; intersperse flash pieces among the longer ones; don’t put stories with similar family structures side-by-side; mix surreal and traditional stories. I spread the fifteen stories on the floor and shuffled them around like puzzle pieces until I reached a kind of stasis: I couldn’t move one without disrupting five others. Just before the book went to print, I decided to put “Relatives of God” last. I liked the final image: the parents looking at the children, the children glancing back. It felt both recursive and redemptive.

Now after readings, people will come up and say, “I read your last story first” or “I’m skipping around.” Which is, of course, how many of us read story collections. I read the title story in Saunders’ Tenth of December first, even though it’s the final piece in the book, because everyone kept saying “you have to read this story.” Still, the order is important to me, if only for personal aesthetic reasons. And readers who do move straight through might appreciate the time I spent agonizing.

S[r]: Although a similar underlying current propels your stories, this was one of the most stylistically diverse collections I have ever read. The differences in point of view, tense, quotation styles and chronology were refreshing and impressive. Is there anything you can’t do?! What story took you the most out of your comfort zone and how did you overcome that?

JQ: “Demolition.” No question. I wanted to try a Millhauser-esque “we” narration, and it proved a big challenge. And what actually happens in that story—the cave, the undressing, the kudzu—that all took me by surprise. I didn’t want the ex-parishioners to go in that (deeply unsettling) direction. Alas, by the time they started going there, they were running the show entirely.

S[r]: Despite the diversity in your collection, there are several similarities between the stories involving infidelity. Many of these similar details were so beautifully subtle that I had to go back to make sure I wasn’t imagining them. There is a nameless woman in an emotional affair—some stories divulge that she has been married for seventeen years; others involve her four children, a pastor and most frequently a four year-old son. Is this character indeed the same woman? If so, were these stories once part of a larger one, and how did they evolve into the collection as they are now?

JQ: Yes, they’re meant to be linked: same woman, same lover, same families. My editor and I had to go through and make sure all of those details lined up. And no, they were never part of a longer work. In fact, all of the flash pieces, as well as the three short sections of “What Friends Talk About,” began as poems. I was obsessed with the material and wanted to see how far I could push, how deep into the well I could go.

S[r]: On a similar note, “Georgia the Whole Time” is a prequel to “Here,” and in your collection they appear out of chronological order. Which story did you write first and how did that affect your approach to the other?

JQ: “Georgia” came first, “Here” about a year later. Originally they weren’t linked stories—they had different settings, family make-ups, types of cancer, names/ages/number of kids. When my editor and I began working together, we decided the two stories could, in fact, be about the same family. It took some adjusting: adding a child here, taking one away there, making sure the years added up. It was tricky. I had to do math.

S[r]: You’ve said before that it is important for fiction writers to explore unknown experiences. How do you balance the expectations of fiction with the expectations of family or religion?

JQ: I try not to think about expectations when I draft—moral, familial, aesthetic, or otherwise. To write with anything less than complete moral and aesthetic freedom would be a kind of suffocation. Of course one can make adjustments in the revision stage. But freedom from stricture while drafting is essential to the authentic writing life. I think of what Barry Hannah said about music, its relationship to prose: “it’s ineffable. It is the highest thing you can reach for. It is beyond good and evil; that’s why I don’t like to attach morality or philosophy to the deepest things I feel. They’re just beyond it.”

S[r]: What fabulous advice. Thank you so much for taking the time to answer our questions, we look forward to seeing more from you in the future!

Eric Maroney is the author of two books of non-fiction, Religious Syncretism (2006) and The Other Zions (2010). His fiction has appeared in Our Stories, The MacGuffin, ARCH, Segue, The Literary Review, Eclectica, The Montreal Review, Pif, Forge, Per Contra, Stickman Review, Samizdat, and Jewish Fiction. His non-fiction has appeared in the Encyclopedia of Identity and The Montreal Review. His story The Incorrupt Body of Carlo Busso was the runner up for the 2011 Million Writers Award. He has an MA from Boston University, and lives in Ithaca New York with his wife and two children. He is currently at work on a novel called The Land Before You.

Eric Maroney is the author of two books of non-fiction, Religious Syncretism (2006) and The Other Zions (2010). His fiction has appeared in Our Stories, The MacGuffin, ARCH, Segue, The Literary Review, Eclectica, The Montreal Review, Pif, Forge, Per Contra, Stickman Review, Samizdat, and Jewish Fiction. His non-fiction has appeared in the Encyclopedia of Identity and The Montreal Review. His story The Incorrupt Body of Carlo Busso was the runner up for the 2011 Million Writers Award. He has an MA from Boston University, and lives in Ithaca New York with his wife and two children. He is currently at work on a novel called The Land Before You.