For some people, “serious art” is a compound word. They say it with the most severe reverence that is usually reserved for funerals and graduation speeches. These are people who think that good art can’t be silly, or that silliness can’t be sincere or profound.

For some people, “serious art” is a compound word. They say it with the most severe reverence that is usually reserved for funerals and graduation speeches. These are people who think that good art can’t be silly, or that silliness can’t be sincere or profound.

However, as any creator knows, art is entirely unpredictable and rule-breaking. Creating something good is like riding an endlessly bucking horse; if the artist wishes to ride any distance without falling off, they must learn to adapt to the horse’s movement.

Mediocre art is very easy to identify; it feels unnatural, restrained, sedated, in chains. A horse that doesn’t buck will never go anywhere interesting. It’s more like taking a pony in a circle at an amusement park.

For critics, there is little worse than making the wrong distinction between good and bad: mediocre art is sincere, however poorly executed; bad art is always insincere. While mediocre artists give us clichés and flat soda, they are not as dangerous as “serious art” snobs.

*

“Silly or serious” is not a dichotomy. Attend a wedding reception to see this in action; watch the bride and groom, hours after making “the most important decision of their lives,” get drunk. Watch their parents get drunk and start reminiscing about baby moments. Also, consider sex, one of the silliest acts. Intercourse is the only time when it is interesting and enjoyable to repeat the same motion hundreds of times, time and again. Yet this is what allows the human race to continue.

*

“Silly or serious” is not a dichotomy. When evaluating art, one must treat “silly” and “serious” as the primary colors of any good work. The mark of a brilliant artist is the ability to be both silly and serious.

This appears in all genres of art, and I’m going to take you through music, literature, and unframed art with such examples as Mozart, Lewis Carroll, YouTube, and Futurama.

*

I love Mozart. I love the calm-before-the-storm-iness of Mozart. I love the crystalline confidence of his scales. I love the catch of his melodies. I especially love how Mozart mixes silly and serious.

Mozart’s canon “Leck Mich Im Arsch” (literally, “lick me in the ass”), is one of my favorite examples of how silly and serious can work together to produce art that is unquestionably brilliant, even if it does make you giggle. Just think that without these lyrics, this would sound like a solemn ode to brotherhood.

Another of my favorite Mozart moments is from his final opera The Magic Flute. In one of Mozart’s most cheerful, upbeat, and memorable pieces, the Queen of Night asks her daughter to murder Sarastro, while exercising insane vocal techniques that singers have to dedicate their lives to attain. It’s a funny song, because the seriousness of the lyrics clash with the flowing lightness of the tune.

The vengeance of Hell boils in my heart,

Death and despair flame about me!

If Sarastro does not through you feel

The pain of death,

Then you will be my daughter nevermore.

It’s a scary song; listening to it, I get chills. And it’s a song that gets me through the day, one I love to sing over and over, under my breath, everywhere I go.

It’s not just the mixing of silly and sincere that makes these pieces great; it’s the undeniable humanity and sincerity of the music.

*

Now consider Lewis Carroll’s “Jabberwocky.” Its linguistic brilliance and inventiveness is first class, as the beauty isn’t in the meaning so much as in the way the plot is actually understandable, despite the strangeness of its language. The atmospheric brilliance of the first stanza is inimitable:

`Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

Its specific nonspecific language allows us to imagine and feel anything, depending on how we enter the poem. Many would write this poem off as silly. Yes, it is silly, but I find serious and sincere qualities in its retelling of the hero’s journey. It is a metaphor for triumph over any conflict in our lives.

*

There is also the problem of unframed art. Some people tend to think that art must present itself as art, and that only certain kinds of art exist. Music, poetry, theater, painting, sculpture, etc… What about TV shows? What about YouTube videos?

This YouTube video by user wendyvainity seems at first to be nothing but nightmare fuel, with dogs. Here is a full synopsis of the video: two dogs sing an auto-tuned song about being dogs while the hairs on their coats grow incredibly long and then shrink back into their body; they jump over each other, and then they jump over what is probably the River Styx. Even on the other side of the river, they keep singing, and their hairs keep growing and shrinking back. Yes, I’d say nightmare fuel with dogs is a pretty accurate term, but—wendyvainity’s video also engages the absurd and the nonsensical to speak about (or at least prime in our unconscious minds) mortality, change, identity, fate, self-consciousness, and the possibility of real connection. Oddly enough, it reminds me a lot of Beckett.

*

The animated sci-fi comedy show Futurama has proven itself capable of genius, but what really makes some of the episodes “art” is the show’s commitment to sincerity. Take for example my favorite episode, “Jurassic Bark.” The episode is a perfect blend of silliness and seriousness.

For those who are not familiar with Futurama, the premise of the show is that Fry, a loser pizza delivery boy living at the turn of the 21st century, accidentally gets cryonized until the year 3000, and must adapt to his new life. A common theme is Fry’s attempting to reconcile his past life with his current existence, and the possibility of his own insignificance.

Why is “Jurassic Bark” such a brilliant episode? Because it confronts cynicism with sincerity.

Here is a brief summary of “Jurassic Bark”: A museum in New New York digs up the remnants of the pizza restaurant that employed Fry in the 20th century. In the exhibit, Fry finds the fossilized body of his old dog, Seymour. After making a show of protesting in front of the museum, Fry gets to keep his fossilized dog. Fry’s mad scientist boss, Professor Farnsworth, says that he can bring the dog back to life. However, Fry’s best friend, Bender, gets jealous and upset with Fry for spending so much time preparing for the dog’s revival.

The episode alternates between Fry’s preparation for Seymour’s arrival in the present, and flashbacks of the history of Fry’s experience with his dog. The flashbacks start with their first meeting, when Fry gets a prank pizza order and shares the unpaid-for pizza with the starved dog in an alley, who follows Fry home. The flashbacks culminate in Fry’s cryonization and the dog’s subsequent search for Fry.

Fry: “I have a pizza here for Seymour Asses.”

Man at Delivery Address: “There isn’t anybody by that name here. Or anywhere. I hope in time you realize how stupid you are.”

Fry: “I wouldn’t count on it.”

At the end of the episode, learning that the dog lived for twelve years after Fry got cryonized, Fry succumbs to the contagious cynicism of his coworkers, and decides, for the first time in his life, to be ‘emotionally mature’ and to let his dog stay dead. The last lines of the episode (as given by IMDB) are:

Fry: I had Seymour ‘till he was three. That’s when I knew him, and that’s when I loved him… I’ll never forget him…

[Picks up the fossil and looks into its apparent eyes]

Fry: But he forgot me a long, long time ago…

But the episode doesn’t end there. The episode ends with a montage of the twelve years Seymour spent waiting in front of the pizzeria for Fry’s return, accompanied by a beautifully sung rendition of “I Will Wait for You” from The Umbrellas of Cherbourg.

Good writers are deliberate, and every detail in “Jurassic Bark” is necessary to the episode and has some poetic value. I am going to offer a few of the most striking motifs, and some parts of the episode that I think embody them. As a warning to the reader, many of these examples are extremely specific and require a familiarity with the tropes and characters of Futurama:

The buried past is still alive in some form: fossilized Seymour, flashbacks… False emotional showiness: Bender the magician, Leela dramatically stripping and running to the lava, Bender emerging from the floor like a volcano, Bender’s robot dog… Cynicism as a destructive force: Bender’s throwing the fossil into the lava, Fry’s parents ignoring Seymour’s barking at Fry’s cryonized body, Fry’s ultimate decision not to recover Seymour… Cynicism as learned behavior: Fry is Bender’s apprentice, Fry’s ultimate decision… Sincerity as something frowned upon: the crew’s lighthearted scorn of Fry’s three-day dance-protest to get his dog from the museum, Bender beating up Zoidberg after Zoidberg explains Bender’s magic trick to the audience, Bender choosing to believe that Fry’s emotions are fake and that Fry is only acting that way to make Bender feel bad… Sincere connection as a rare and valuable ideal: Seymour is weak at first but grows healthy when fed and given love, Fry is only happy when with Seymour, Fry and Seymour are lonely and outcast but fill a void in each other’s lives, symbolized by their ability to sing together “Walking on Sunshine”…

Many viewers, angered by their own emotional responses to the episode, have complained that the ending of “Jurassic Bark” is manipulative, and rightly so; like all great stories, we are tricked into feeling emotion for people that don’t exist and the decisions they make. Where the objectors are wrong, however, is in denouncing this manipulation. Yes, we are tricked, as many great writers have tricked us in the past. We are tricked into first believing that Fry is making the right decision (a triumph for cynicism), and then shown that his dog never stopped believing and just kept waiting. In the end, moved to tears and anger as many viewers are, we ourselves are the triumph of sincerity.

*

So. What’s the takeaway? Why is any of this important?

Silliness is the most underrated aspect of art.

More than anything, sincerity is what counts.

Art doesn’t have to be serious to make you a better person.

If you can be a silly genius, more power to you.

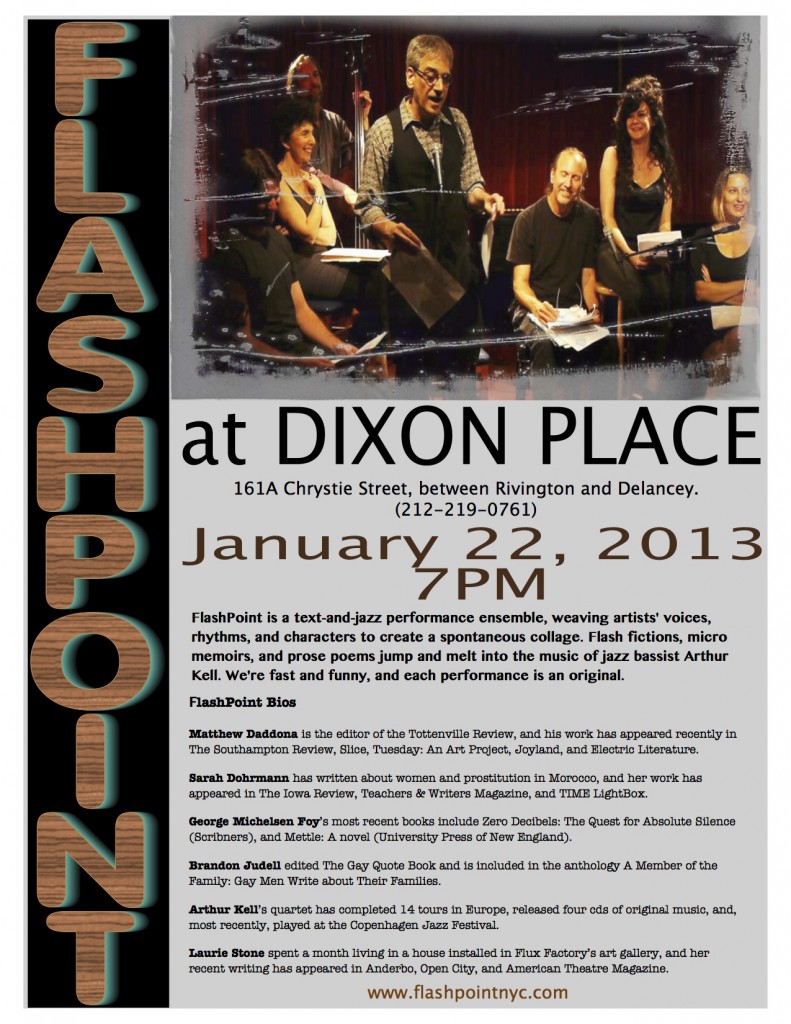

Being both a writer and an artist, I often get the question of how can you switch from one medium to the other? To be honest, I don’t consider that I’m switching. It’s all in your head (or mine, I suppose). There are so many elements that cross over from one medium to the other—metaphor, imagery, form, symbolism, etc. that I don’t think I need to belabor that point. And of course there are very narrative artists such as Magritte or Joseph Cornell. And there are many other artists who are also writers or actors or musicians (William Blake, Terry Allen, Tony Bennett, Patti Smith, to name a motley few). And when I lived in New York, it seemed that everyone was writing a screen play, sculpting and playing in a band or photographing, juggling and tap dancing or putting together dance, jazz, projected painting performances or some variation of any of the above. Doesn’t all creativity spring from the same source?

Being both a writer and an artist, I often get the question of how can you switch from one medium to the other? To be honest, I don’t consider that I’m switching. It’s all in your head (or mine, I suppose). There are so many elements that cross over from one medium to the other—metaphor, imagery, form, symbolism, etc. that I don’t think I need to belabor that point. And of course there are very narrative artists such as Magritte or Joseph Cornell. And there are many other artists who are also writers or actors or musicians (William Blake, Terry Allen, Tony Bennett, Patti Smith, to name a motley few). And when I lived in New York, it seemed that everyone was writing a screen play, sculpting and playing in a band or photographing, juggling and tap dancing or putting together dance, jazz, projected painting performances or some variation of any of the above. Doesn’t all creativity spring from the same source?

I have been thinking about the ways in which musical and verbal intelligences merge in a poem as compositional strategy, because I have wanted to understand how a poet “thinks” through the music of the poem, as distinct from stating a thought directly as an abstraction or translating it visually into imagery. What interests me is the way a poet puts sonorous “truths” in play. These “truths” are not always articulated thematically in the poem, but the poem’s music gives rise to them, in the musical supplement to signification that Northrup Frye called the “babble” of poetry.

I have been thinking about the ways in which musical and verbal intelligences merge in a poem as compositional strategy, because I have wanted to understand how a poet “thinks” through the music of the poem, as distinct from stating a thought directly as an abstraction or translating it visually into imagery. What interests me is the way a poet puts sonorous “truths” in play. These “truths” are not always articulated thematically in the poem, but the poem’s music gives rise to them, in the musical supplement to signification that Northrup Frye called the “babble” of poetry.