Following is an interview conducted by Superstition Review‘s Poetry Editor, Erin Peters.

Jaclyn Youhana Garver is a freelance writer in Fort Wayne, Indiana. She writes fiction and poetry, and she has been featured in Narrow Road, Poets Reading the News, and Prometheus Dreaming (forthcoming). Her work has also been chosen by the Wick Poetry Center as a Traveling Stanza selection.

Jaclyn’s Poem:

A COLLEGE GIRL MAKES WARDROBE DECISIONS BASED ON THE POSSIBILITY OF A RANDOM TSA SCREENING

1964

White kid gloves / cinched waist / her perched hat the

precise plum match to her two-piece suit / a corsage

(seriously, a goddamned corsage)

/ a Cherries in the Snow pout / a blushing visage

coral or rose / a fur, perhaps, in beaver or lamb.

2004

Pajama pants, peppered in cartoons / flip flops

with jewels that stud the thongs / pigtails

(seriously, goddamn pigtails)

/ a gray T-shirt that boasts,

“Journalists do it daily.”

Don’t look at me, Terry, standing in line. I know

you’ve a quota to meet, so many at random

searches to complete to assure you don’t permit on

the plane any drugs, bombs or hydrogen dioxide.

(Water, Terry, I’m talking about water.)

It doesn’t matter, though. You’ll search me nonetheless,

just like that agent last time and the agent who’ll be next.

And anyways, I’ll stick with PJs and pigtails, my sandwich

board to shout I’m threatening like sidewalk chalk, an eagle

scout, freckles, and winks, but apparently, the extra melanin

in my skin, a gift from my father, means you must pull me

from the line, away from my friends—none of whom you

also select at random, I see, goddamn it, Terry—so you

run the backs of your Caucasian hands along my Persian arms,

my cartooned inseam, my Assyrian torso. Then you make me move

my Iranian pigtails from my Middle Eastern shoulders.

You look so bored, Terry, and I wonder if you notice:

We’re quite the chatty portrait of our country tis of thee.

Interview With Jaclyn:

The setting of your poem is very specific and relatable for people who have travelled in American airports. What inspired you to write about the experience of a TSA screening?

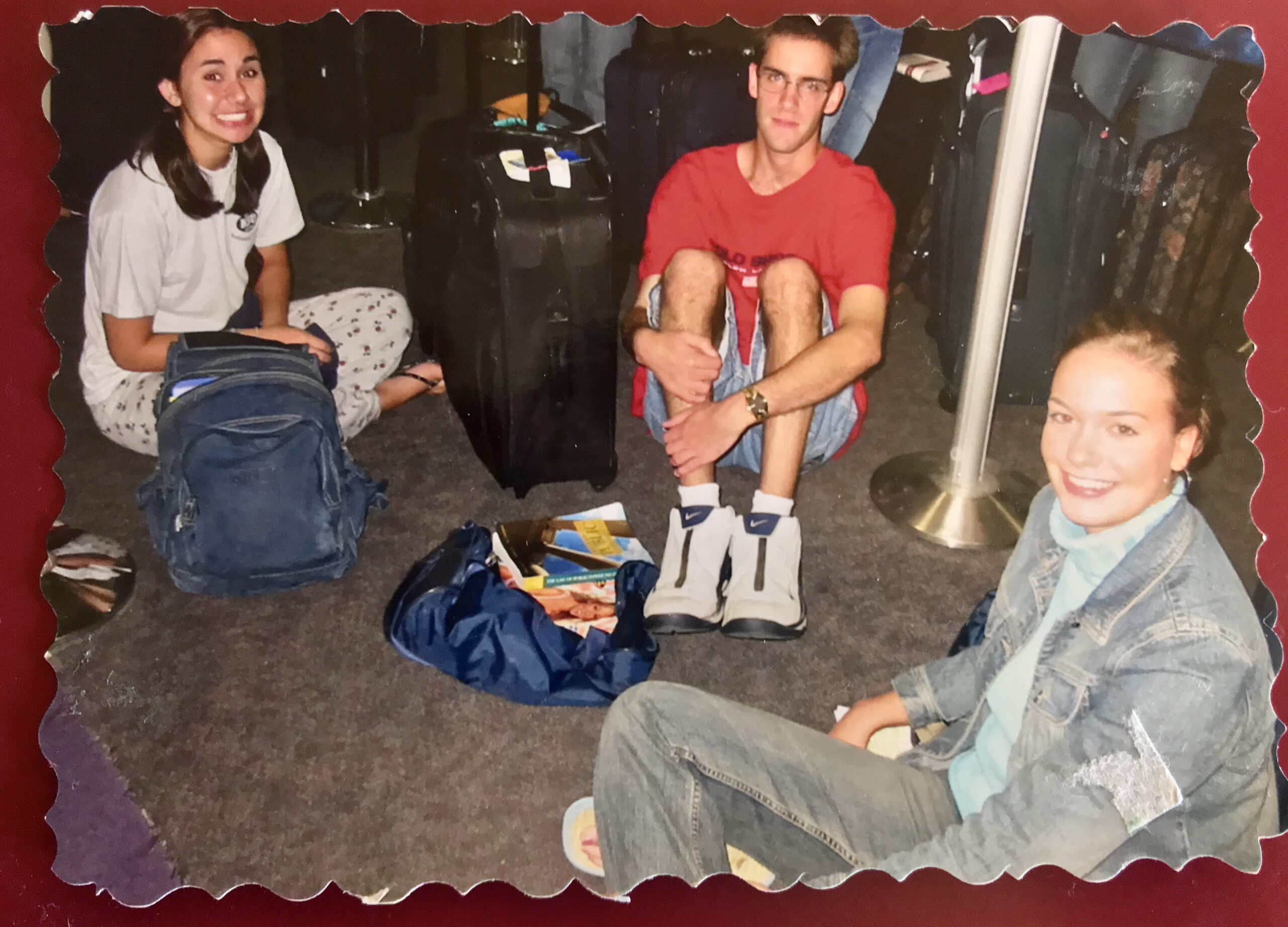

This summer, I found a photo of myself at an airport in 2004, with two college friends, on the way to a Society of Professional Journalists conference in NYC. For the three or so years after 9/11, I began to be “randomly” searched on every flight I boarded. Seriously. Every flight. I thought it would help if I dressed in an unintimidating way. I remember I did this each time I flew, but it was wild to see photographic proof, especially compared to two other young adults who were dressed in, you know, normal airplane-appropriate clothing. Finding the photo, seeing how 21-year-old me felt like she had to dress, seriously pissed me off.

You’ve spent an impressive amount of time working for daily newspapers during your professional career. How do you feel this writing experience impacted you creatively?

I can’t even imagine writing creatively without my journalism experience. Writing for a daily newspaper made me completely deadline-focused. If a journalist doesn’t finish her story on time, there could an actual hole in the newspaper. Plus, the piece needs to be done well and accurately, often in hours or less—journalists don’t have days and days to perfect a piece of writing.

I adore the saying Done is better than perfect. Writers, especially creative writers, can get stuck in this I can’t show this to anyone because it’s not perfect hole. Then nothing ever gets finished. Writing for a daily newspaper was a wonderful way to keep from being too precious about my words. What I write matters, and it’s important to me, but once I turn in a story, it’s on to the next thing.

Writing for daily publication also gave me tough skin. I adore editor feedback and love seeing how subsequent drafts improve. Similarly, I also trust my gut. Writing is a wonderful mixture of both subjectivity and objectivity, even in poetry. My newspaper experience gave me an almost scientific approach to being creative.

What audience do you hope to reach through your poetry? Why is this audience meaningful to you?

As a reader, the best feeling is “Oh my goodness, you too? I thought I was the only one.” As a writer, then, that’s who I want to reach—anyone who has felt like me, to help them feel less alone. Strangely, the opposite is true, too: It’s such a rush to be told “I never thought of it in that way before.”

Those audiences are meaningful to me because it means we have a shared experience. Especially in 2020, feeling a connection—to anyone, even some writer you’ve never met—is vital.

How has the global pandemic impacted your creative process?

The pandemic hasn’t impacted my creative process so much as it’s impacted my creative output. I’ve written poetry since I was about 12 and I had a writing minor in college, so writing creatively has always been a part of my life. However, the pandemic made me itch to do more. I answered that by enrolling in a poetry class. The instructor helped me figure out what was missing from my poetry unlike any writing teacher I’ve had before. After the class, I asked where she was teaching next, and I signed up for that class, too. She helped me see where and how my work could be improved, which simultaneously showed me how to edit my own work.

This year has been hard, and there are a few things I can point to and say “That, specifically, made things a little easier.” Writing poetry is one of those things.

What is the most important piece of advice you have received as a writer?

In college, a journalism professor taught us to let the other person have the last say. When someone reaches out to a reporter to complain about something they wrote, the caller or emailer doesn’t actually care what the writer has to say about it. They just want to be heard (and maybe to be nasty). That knowledge, that someone who has something mean to say isn’t looking for a response, is incredibly freeing.

What are your upcoming projects?

I have a number of manuscripts in the works, but two are currently taking up the most of my time—a poetry book and a women’s fiction novel, which I will be pitching to agents early next year. I also write horror short stories. I love bouncing between genres and working on projects of varying lengths.