Ampydoo the cartoonist is otherwise known as Alan Michael Parker, the author of four novels, nine collections of poetry, and coeditor of five scholarly volumes. Parker’s awards include three Pushcart Prizes, two selections in Best American Poetry, the Balch Award, the Fineline Prize, the Lucille Medwick Award, the Randall Jarrell Prize (three times), and the North Carolina Book Award. In 2021, he judged the National Book Award in fiction. He holds the Houchens Chair in English at Davidson College, where he teaches courses on experimental fiction, creativity studies, and inhumanities; his cartoons appear each Friday online in Identity Theory. To view more cartoons, visit Ampydoo’s website.

We are please to present an interview with Alan Michael Parker below, conducted by Addie Ascherl—one of Superstition Review’s art editors for Issue 31. Please note that the transcript has been edited for clarity.

Addie Ascherl: Hello, my name is Addie Ascherl, and I’m Superstition Review’s Art section Editor. Today I’m interviewing Alan Michael Parker to discuss his art. He is extremely multifaceted, being a poet, novelist, professor, and cartoonist. He creates his comics under the pseudonym “ampydoo.” Am I pronouncing that right?

Alan Michael Parker: You are.

AA: His works are published weekly in the online literary magazine Identity Theory. Thank you for talking with me today and I’ll give you the chance to introduce yourself, if you’d like.

AMP: Well, I’m still ampydoo, Alan Michael Parker, and this is Addie, with whom I’m speaking. I’m talking to you from the historical property of the Catawba Nation—a little land acknowledgment, just getting that in there. This is my studio, so I’m in my house in North Carolina—upstairs in my house. There used to be books—there still are books—but they’re kind of hidden over there, because I went and did something different during the pandemic, which is I started drawing. And now I can’t stop. That’s my intro.

AA: What about the cartoon medium speaks to you, and do you have any inspirations or similar artists that you look up to?

AMP: Oh, wow, yeah. The inspirations and artists, it’s a really long list. And in fact, I have one of my commitments when I started doing this was to put together exactly that kind of list and to keep it current. And so I’ve got on the Ampydoo Cartoons website, I have a page called “People Are Great,” and I’ve got about 100 people that I’ve linked to their Instagram or their website or just work of theirs that I like. And I would say probably three quarters of them are doing cartooning in some way, but then there are a bunch like I haven’t gotten to. I need to update it. In fact, talking to you, I was like, “Oh, dang, I should update my ‘People Are Great’ page.” But of particular importance, I have to think about that.

So certainly some of the great, most familiar names would be Maira Kalman, Gary Larson, Bill Watterston—I mean, some of the comic artists through the years, definitely Art Spiegelman, very important people. And I’ve taught these artists often, but just hadn’t made my own work before. And then people I’ve discovered along the way would be the total weirdo who was Abner Dean; an artist on the West Coast who I admire very much named Johnny Damm, doing a lot of political work. A person I’ve come to know a little bit and really like is the co-editor of the Comics Journal named Austin English. He just sent me this zine from an artist from Julliete Collete called Blah Blah Blah… Tara Booth, Liana Finck, GB Tran—these are all living, wonderful, amazing, working artists. Kate Beaton has a new great graphic memoir about growing up in Western Canada. On the whole, I’m not choosing graphic novelists or sequential art. On the whole, the folks who are moving me most are people doing what I’m interested in, which are these single-panel cartoons that are sometimes called “gag cartoons.” That’s the genre because it has a gag punchline, but I don’t know what else to call them…

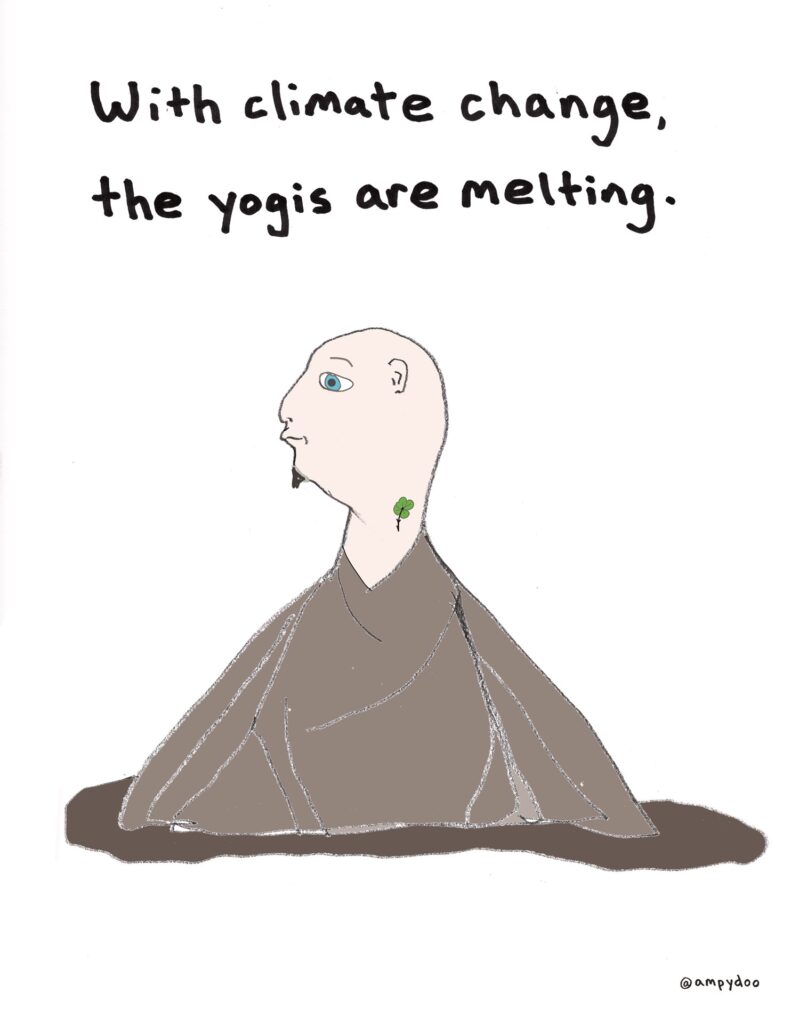

What draws me to the medium, to flip-flop my answers to your questions… I’m fascinated by the combo of image and text that have to work independently, that unto themselves are already, between a caption and an image, a kind of hybrid genre, because it’s writing and it’s art. And that fascinates me. The sense that both the image and the text have to be independent, and have to further the ambitions of the other, in these one-panel pieces, fascinates me. That really draws me to the form.

AA: Yeah, and I feel like, the fact that it’s a single page often can be an interesting way of, not constraining you, but you almost have to think outside the box.

AMP: Yeah. Oh, no, that’s a constraint. It’s a formal constraint. It’s not so far from, in that sense, the kind of constraint you have when you have to write a sonnet, or when you say, “I’m going to do a drawing of someone’s eye, and I’m not going to let myself change.” It’s just going to be the eye and then keep going and getting granular with the detailed, microcosmic, just getting in there as much as possible. I mean, there are formal constraints.

I have all sorts of wack theories about the way cartoons work now that I’ve started making them. One of them is that I have roughly seven seconds to get you to want to read past the joke, into something else. I have seven seconds to deliver a joke that you get, and then that has to push you further. It’s a wack theory.

AA: No, that’s interesting. I hadn’t thought of it that way, but that makes sense. You have a singular focus that you want people to understand and want that to translate.

Another question that I have is… A vast majority of your comics have a humorous tone. One in particular I noticed is titled “The Mona Lisa from behind,” in which the back of a woman’s head appears to be much more simple than the complex Da Vinci painting we are all familiar with. Could you describe your process for making these comics? And coming up with such ideas?

AMP: Sure. I can describe the process. I’m coming at this medium as someone who has a long history writing poems, as well as flash fiction. The sense of the encapsulated, narrative moment, the ability of a poem to create offstage, subtextual, and psychological meanings that are resonant beyond the denotative. They imply or intimate or make meanings off the page, in your head, that stuff really interests me. That’s very much part of my process and part of my goal.

The literal process is that I’m drawing in ways that are sometimes doodling, sometimes inspired by everything from infographics to pictures of animals to something that I saw on the web. When I first started, I would put a piece of paper on top of you and trace your head, and then I’d have the rough outline. And now I’m learning—I’ve got like this much more skill [pinches thumb and index finger together] as someone who draws. But I’m trying to trust my freehand drawing, and then very much early on in the drawing process, I begin to work with what I think might be the narrative that’s implied or the caption I might deploy.

After the drawings are made, and they’re made in alcohol-based markers—they are my markers—as well as pencil and sometimes, as you can see from behind me, charcoal. Then, I scan them, and I have a pretty high-end, nifty scanner, and then I work in Photoshop. So what you’re seeing is digital work, and it’s meant to be digital. There are high-end print-outs, and that’s what this stuff is [points to the left]. My printer’s good, color mixing is good… And my monitor is good. I have good studio equipment, good tech. This is digital work, fundamentally digital work.

Having said that, I’m also interested in what it looks like if you put it in a book. I like the notion that the work is not as precious as poetry. I like the fact that it’s on Instagram, I like the medium being disseminated. It suits my Neo-marxist, semi-capitalist, full-disclosure, freeware aesthetics, shareware, cultural commons, kind of like, “Get the work in the hands of people who are gonna giggle.”

AA: Like fully accessible, kind of, I guess.

AMP: Mm-hmm.

AA: I thought they were completely digital. I didn’t realize that you actually physically draw on paper. I thought you used maybe a tablet—because, I don’t know… I just assumed, I guess.

AMP: I tried a tablet, and I found I didn’t have enough command. And I really like this mix of—and it sort of suits me—like, for the Mona Lisa one… This mix of the hand-drawn and then the Photoshop, the lettering being Photoshop. And I’m willing to make them, to sort of give into their DIY, self-trained art tendencies. I’m not looking to be Edward Hopper, here. I like the imprecision of the artist’s hand, the brush work being visible. I think it, to me, it’s expressive, it communicates the brain of the maker. And that, in this art form that’s relatively new to me—as someone who makes these things—I find it kind of fascinating.

But I didn’t answer your question! There was another question about sneaky, dark meanings. Was that your question?

AA: That’s my next question.

AMP: What was the question about the Mona Lisa then? Oh, about the concepts—where the concepts come from. Yeah, yeah, yeah. So, drawings first. Captions second. There. I think because I’ve been a writer for a billion years—because I’m old—that the captions feel much more fungible. Like I could throw them out and try another one. I’ll write thirty captions in my head or take ten in my sketchbook, with each drawing. And I’ll run them by my partner, and she’ll say, “No, no, no, no, no.” Well, she likes saying “yes” to the captions, but they all stink so she’s right.

At some point, that helps me get there. I am interested in the least number of words. That is a goal. Sometimes that’s fifty words. Sometimes it’s four. Or two.

AA: Okay. Interesting. Yeah, going on to the next…

AMP: Sorry, I read ahead in the lecture! Sorry.

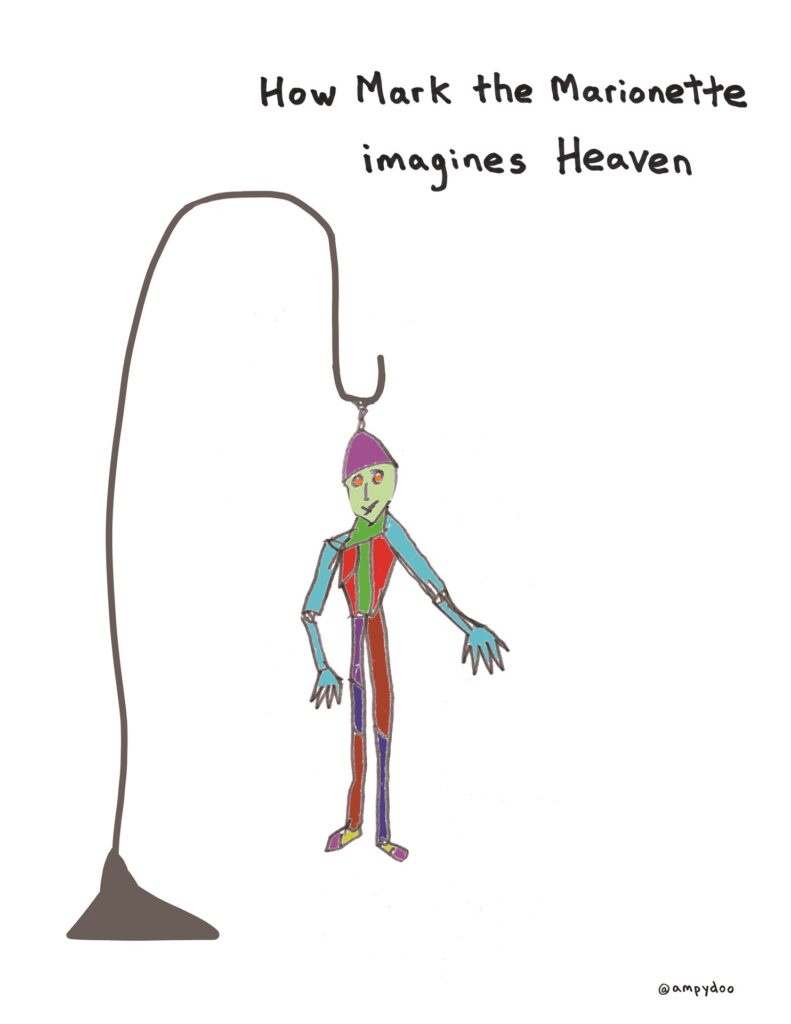

AA: No, it’s all good! A vast majority of them are humorous, with one-liners that accompany the images. But some do have a seemingly darker nature, I noticed. I couldn’t help but feel as if… The comic in particular, “How Mark the Marionette imagines Heaven”—it’s almost cynical, with the perspective, in my eyes, of the puppet being controlled. What are your intentions with these more cynical perspectives?

AMP: Well, if you let me share the screen, I’ll show Mark and talk to you about it. Can you make me co-host for a second? Know how to do that?

AA: I believe so. Did that work?

AMP: Yeah! I think that worked. Okay, so… You have Mark now?

AA: Yes.

AMP: Great! So, first of all… It’s just a really scary, shitty moment in history. And it’s pretty hard for me to simply make humorous work, despite my deep interest in comedy, and not think harder about the scariness. Not want some element of that… Or inevitably, just simply have some element of that out me. Sometimes I do think that kind of content outs the artist, rather than the artist names the content.

I had to wrestle a lot with this. It’s one of those things that, if I were 20 years old, I’d be up till four in the morning with the candle burning. And I’d be staring at it and saying, “What does this mean? How can I make jokes? People are really, really not happy. There’s a pandemic! What does this mean? What does this mean?” And one of the things I’ve come to understand is that there’s an honored tradition in literature, certainly, of the fool—as well as the court jester—and the way in which those people speak truth to sadness and truth to power. While being funny. And without full-on satirical novels—which I have written in the past—this form lets me speak truth to sadness, speak truth to power.

“Mark the Marionette…” So, he gets to hang there without any strings. That might be heavenly for a marionette; that’s possible. But also, he doesn’t get to walk around, and, in fact, being free of the strings, he still needs something to hold him up. So the ambiguity of that, which I think is in his physical gestures and also the fact that this is what he’s imagining to be Heaven… As in, he’s not imagining anything where… He can’t imagine walking around. He can imagine being without strings. So maybe it’s a failure of Mark the Marionette’s imagination. Maybe it’s a comment on that, in some ways. It’s also kind of just… creepy-sad for our Marky-Mark.

AA: Yeah, no, I like this because it’s not obvious, I guess. I really had to think about it, so… Which is interesting because it’s so—such a short line.

AMP: Yeah! It’s one sentence. It’s a very apparently simple drawing of a puppet, colors, hanging on a—I don’t know—a plant stand? I don’t even know what that is. But he’s hanging. And I’m glad that the simplicity of it is what’s drawing you in. Because that’s very much my goal.

AA: Yeah, it very much does. You think it’s supposed to be easy to come up with the idea.

AMP: I don’t really do easy. I love the notion that things look easy, and as a result you get sucked into them. And when you get into them, the ideas are hard. That tends to be my jam.

AA: It definitely reflects, so that’s good.

AMP: Good! Shall we stop sharing? We stop shared. We’re back.

AA: Oh yeah. I did have a follow-up question. So what are some broader issues that are most important to you—that you try to portray in your cartoons?

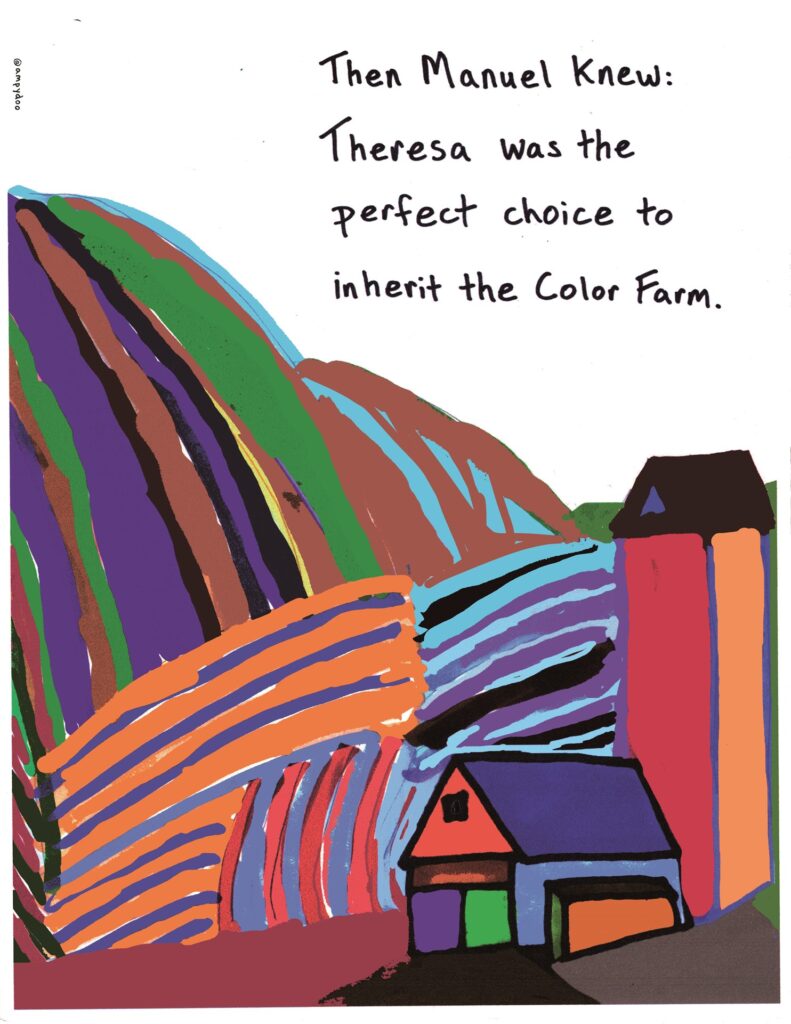

AMP: I’m very much interested in gender. I don’t handle body dysmorphia and gender, but I think a lot about gender. I’ve done some gender studies scholarship. I think a lot about misogyny and sexism. I’m playing hard with identity issues that I usually give to animals, or I give to humans looking at animals or animals looking at humans. Most of the political stuff that happens in my work happens between cross-species. Some of that has to do with my own feelings about appropriation and being a cishet white guy and not believing that I could represent experiences that are so distinct from my own that I’m bullshitting to try to make my neoliberal cause somehow.

But some of it, too, is that I just love funky animals. I’m turning funny, funky animals into… I’m not differentiating people or animals by physical signifiers. There aren’t white animals or Black animals or Latinx animals. It’s not George Orwell… But I really think that animals give me a good way into sociology and into social practice. And also into questions about how screwy people are. Which is probably my subject. I think it’s just, ultimately, just like, “People are screwy.” So my job is to show that.

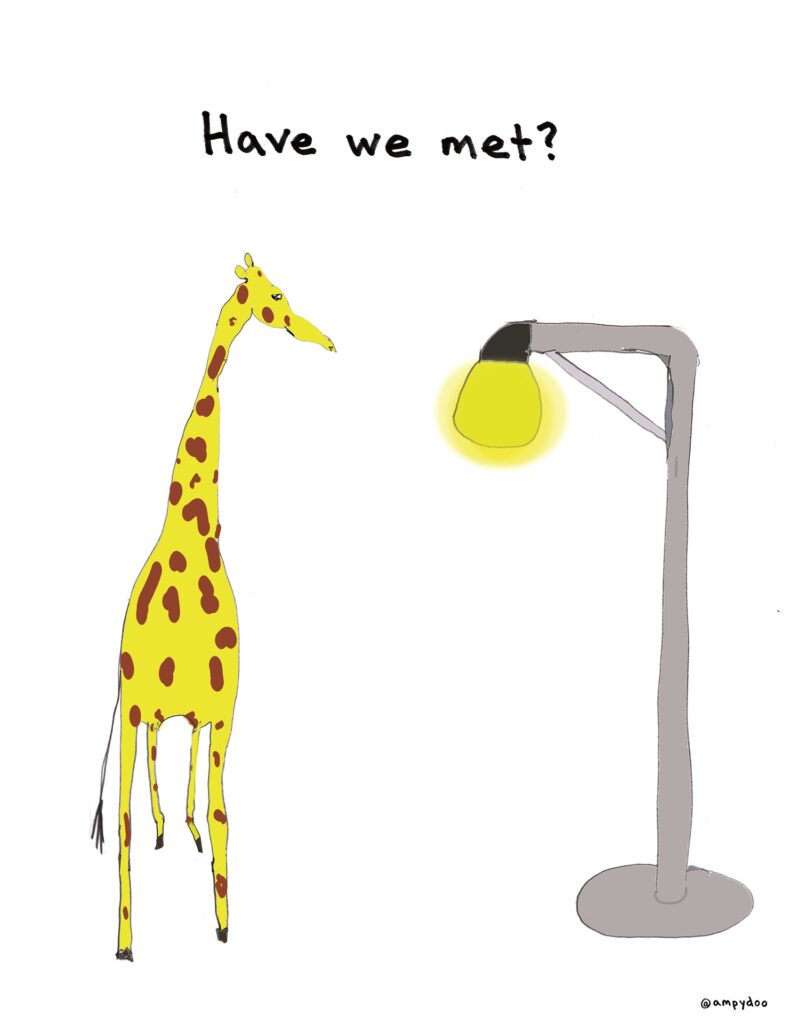

AA: Yeah. Well, that kind of did go into my next question. A lot of your drawings, the subjects are often animals. There’s one I noticed, “Have we met?” It’s the name of a cartoon picturing a giraffe face-to-face with a lamppost—with similar height and stature. And then, I guess, you did go into your inspiration for this anthropomorphism idea and theme. Yeah. Is there anything more you’d like to say about the animals interacting with human-made objects?

AMP: Yeah, so… Pretty clearly the giraffe, here, is looking kind of surprised, I think. I hope. By the “cousin” that the giraffe has just met. One of my goals in this is actually make you believe that the giraffe is asking the question when it could also be the lamppost asking the question. And that’s part of the wackiness, of my humor—is that I don’t want to say. It’s not, “Have we met?” said the giraffe to the lamppost—or vice versa. And the anthropomorphism lets me do that and lets me think hard about the physical world, that very often objects in my cartoons are sentient. There’s a kind of animism to them, if you want to think about them in religious terms, which is that they have souls. They have thoughts. And again it’s an excuse for me to talk about how screwy people are.

So I think that, for example, in this the affinity between them—which is clearly physical, the color rhyme that happens, the relationship between their bodies—is all there. And then maybe you go a little further and you say, “Wait a minute, what is the giraffe doing there? Why do we have this? What is this scenario, that gets a giraffe—not in a zoo or in its natural…” You know, and there’s sort of this creeping eco-thing that might be underneath there about animals and technology. Any number of things that I’m also not going to explain. Just let ’em be screwy. I love the absurd, just deeply… My students will tell you—so much so, that I am completely irritating.

AA: It’s another example of the simplicity being… I’m not sure the word, but, you know—you think it’s simple, and then you get confused it’s not as simple as it may seem.

AMP: Yeah. And then may you have a take. So do you think the giraffe is asking it? Do you think the lamp is asking it? Which one?

AA: Right.

AMP: No, I’m really asking you.

AA: I don’t know. When I first saw it, it’s very much, with the text being in the middle, with the two on both sides… It comes across like it could be either. So I agree. But it’s confusing.

AMP: Yeah, who’s saying it? And why? It’s often very much—that’s very much a response to my cartoons. People go, “Why?”

AA: Yeah. Going into the idea—as you said—of the absurd that you like to incorporate into your work… You have a section on your website called “Weirder Earth,” and it deals with ideas like that—that throw all logic out the window, dealing with the absurd. What is your creative process for generating your work in that area? Or just your more absurd ideas?

AMP: Well, I teach a class in experimental fiction writing. And one of the first times I taught the class, I tried to come up with a motto for the class. I just taught it this last semester, but the time before, the motto for that semester was, “Throw a pineapple at it.” Wait, you don’t know what to do? Throw a pineapple at it. My ambition for the weirder-er work is an ambition that persists, and I think, in fact, is getting even more central to the cartoons that I’ve been making. Which is… Go as weird as you can, Parker. Like, what are you doing? Trust it.

And trust the fact that no one really wants my autobiography. I’ve said this before, in other contexts. I go to work; I teach my class; I go to the grocery store (I love to cook, so I’ll buy fresh stuff); I’ll cook dinner; I’ll go home; I’ll read; I’ll watch a hockey game; I do my homework. I do it again. And what I trust is my imagination as a distinctive—as one of the most distinctive qualities that I own—that I have, my characteristic. That’s my bling. And weirder-er is even more so. So I’m trying to get weirder-er. I’m not actually naming it and saying, “Okay, these are weird. I admit it.” I’m actually trying to go beyond those and just trust it. And I think that the artist’s obligation—for me—it’s the inner freak. That’s who I want to be on my cartoons. I want to share the inner freak.

AA: I think it’s very much an exercise because of… Kids are also drawing in art—creative ideas and imagination. And as you grow up, you have a disconnect with it. It’s very interesting… It’s hard, but it definitely shines through in your work.

AMP: Cool! What kind of work do you do? You’re the Art Editor for this super-duper review.

AA: I have an art minor, so I do… I’m in a figure-drawing class right now. That’s really hard.

AMP: Yeah, I’m doing that, too! I’ve never done it in my life. I’ve done it now five or six times. Once a week. It’s hard!

AA: It’s so hard. I just always strayed away from drawing entire bodies because it’s scary. Because if you’re not good at it—if you don’t have practice with it, you’re not good at it. I was just used to drawing, you know, the face. That’s the easiest. Everybody draws that first. So definitely that’s an exercise in and of itself. I need to look at a person and understand, like, how to translate that into methods where you view it.

AMP: Yeah.

AA: It feels like a mental workout. But you can definitely see the results. As I keep working on it, yeah.

AMP: As I say, I’m getting better like this [pinches thumb and index finger together]. I don’t know if you feel that way. It’s like, “Look at that little square on the leg!” That’s like, I did something! And the rest of it sucks. It’s so hard. It’s really gratifying how hard it is, I find. In a weird, kind of perverse way for me. Because… I know how to type. I teach typing. Okay, writing. But I know how to fix—like, I can fix your cover letter. I can fix a poem, within limits. I’m not promising greatness, but I can fix problems. I can’t do that in figure drawing. I can’t fix drawing! It’s remarkably frustrating. And then I’m like, “That was totally fun!” And it’s a complete fail.

AA: Yeah. You can know that something’s wrong, but it’s hard to know why. Like I’ve been struggling with the proportion of legs, but I don’t know why they’re wrong. I just know that they look wrong. Those were all the questions I had for you! Thank you so much.