Coyote Shook is a cartoonist living in Austin, Texas. Their work has appeared in or is forthcoming in a range of American and Canadian literary journals, including The Kenyon Review, Michigan Quarterly Review, Evergreen Review, SplitLip Magazine, Vox, The Puritan, Shenandoah, and The Northwest Review. They were the winner of the 2020 Jeanne Leiby Chapbook Contest with the Florida Review and have received multiple Best of the Net and Pushcart nominations. To learn more, visit their website.

We’re also very excited to share an interview that dives deeper into Coyote Shook’s art. This interview was conducted by our Art Editor, Addie Ascherl. Please note that the transcript has been edited for clarity.

Addie Ascherl: I’ll get started with the first question! On your website, the bio says that you use comics to examine intersections of critical disability studies and the environment. Can you discuss the most common ways these tend to overlap?

Coyote Shook: Yeah! Right now, I’m doing my dissertation on the history of whaling in the US, and I’m doing it as a graphic novel, but I’m looking at intersections between whaling and disability. For the first half of it, I’m looking at how these interactions with whales maim and dismember whalers and cause them to enter the status of disability.

And then the second half is really looking at where we are now with the environmental movement and also the disability liberation movement. And how both of these movements seemed to, in the 1970s, have gotten caught up in this Neo-liberal, individualistic model, where the emphasis isn’t on radical action or sweeping change. It tends to be more on an affective response to the environment being destroyed or an affective response to requests for disability justice—so where these movements kind of lost momentum in this period of time in the 1970s, where we have this potential for liberation. And then we go into the ’80s, where there’s more of a conservative backlash, and again you come out of out this system of, “You can protect the environment by watching a sad movie about whales.” There’s no real call to action attached, and just how that has become an anemic thing.

There’s other ways I think about that, too. One of my pieces I just got published was all about the archival research I was doing for a different project in Montana a few years ago—and being there during the hottest time of the year. And thinking about the impact climate change has when you’re disabled, and how climate change is disproportionately going to impact people who are disabled. So that’s a lot of where my mindset is around these two fields.

In terms of how comics fit into that—one, I think, as a disabled person, I’ve written a lot about comics as a useful research tool, to think of comics as research because it gives people the right to present things the way that they understand them or in the way they remember them and recreate their sort of reality. Or, if you want, it’s a totally plastic universe. So you can create your own image of the way that something happened or the way you remember something—or the way you might wish something had happened. I find that to be really useful and engaging.

And then, from a practical standpoint, I find that people are always more willing to read something if it’s in a graphic novel. Instead of spending four years working on a book that would sit on a shelf and that no one would read, I’m hopeful that I can turn this into something that’s useful and that people want to read and engage with. That’s a very long-winded answer for that, but yes. That’s kind of how those three fields show up in my work.

AA: Nice! That goes into my next question—which is, how do you represent these topics within your art? And you kind of talked about through the visual medium, and being able to adjust that to reflect your own experiences. But what is a piece of yours that speaks greatly about these issues that you stated?

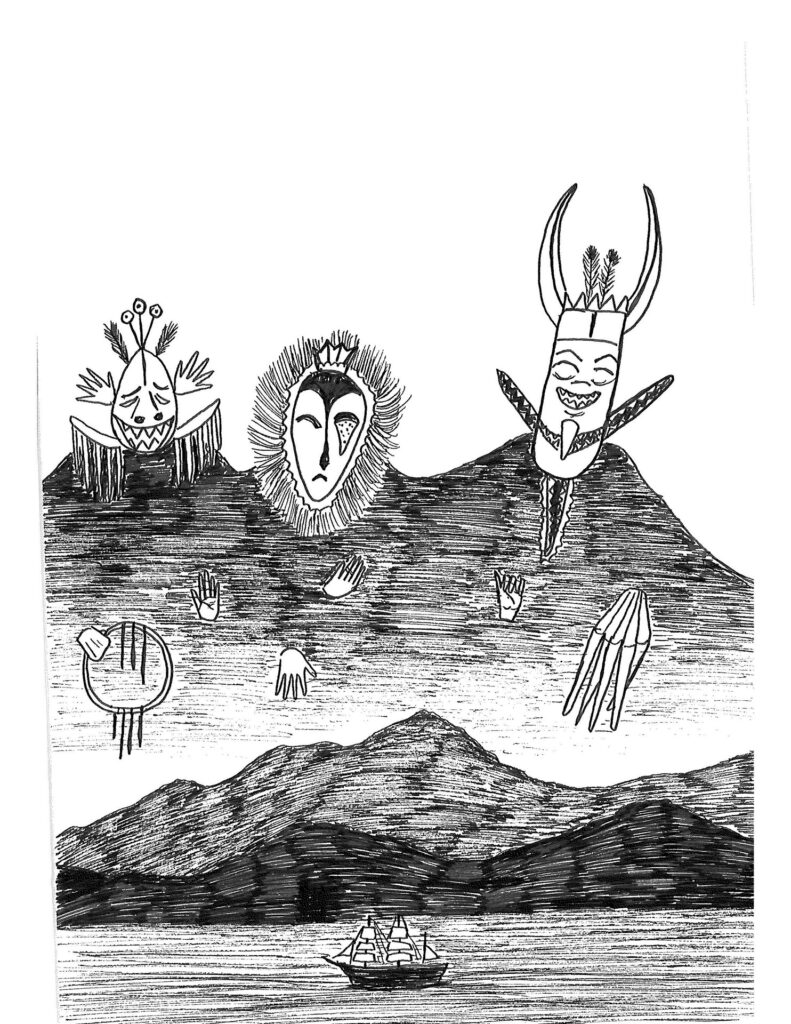

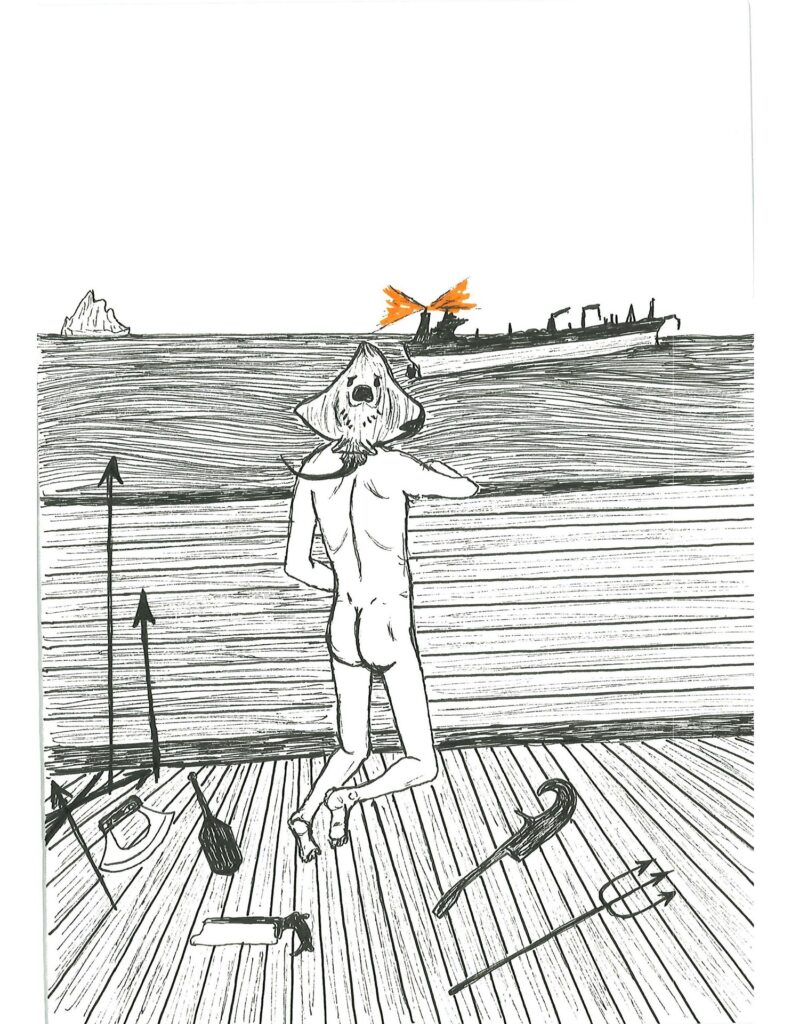

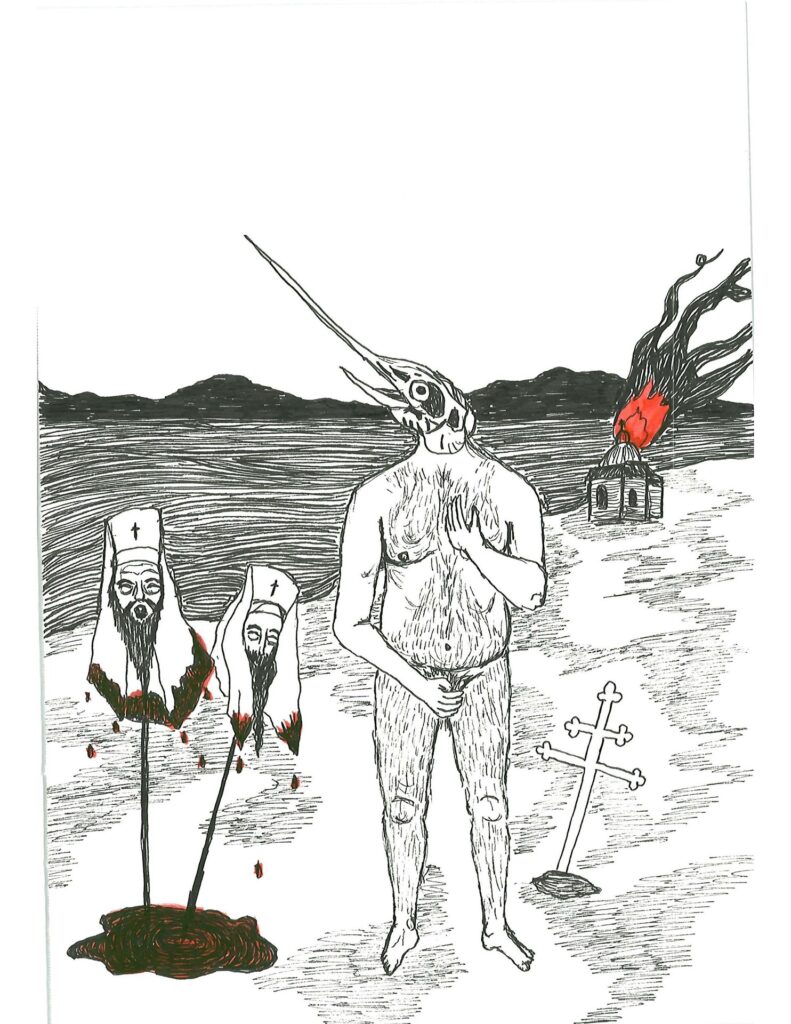

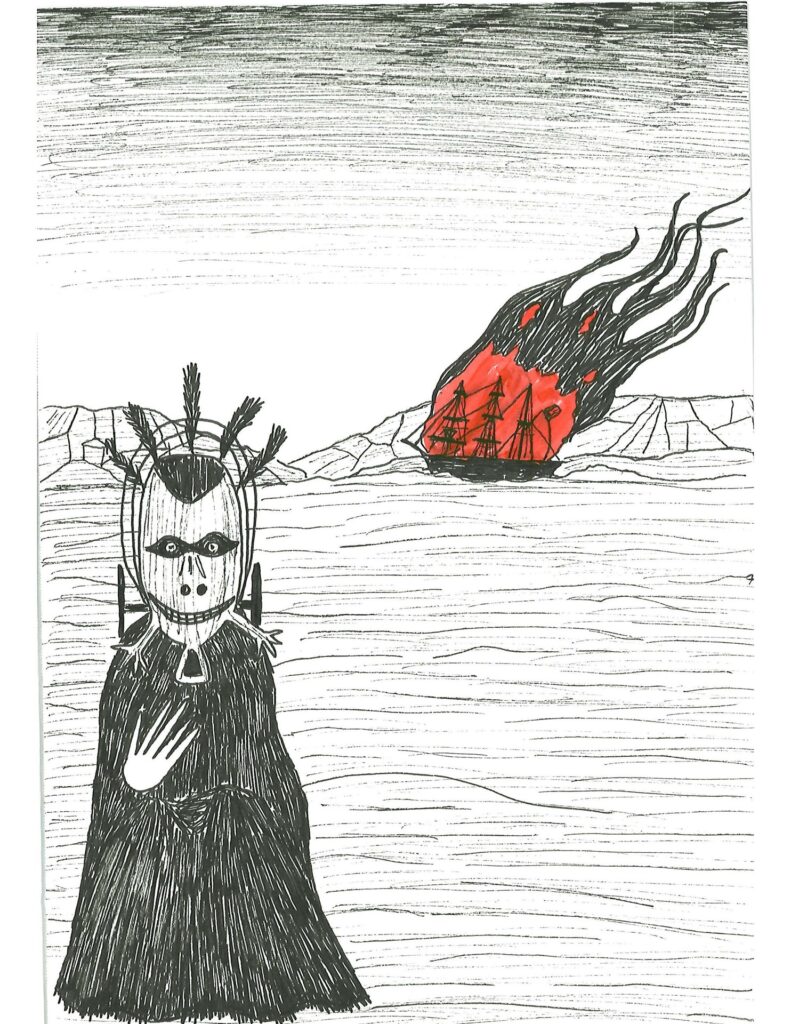

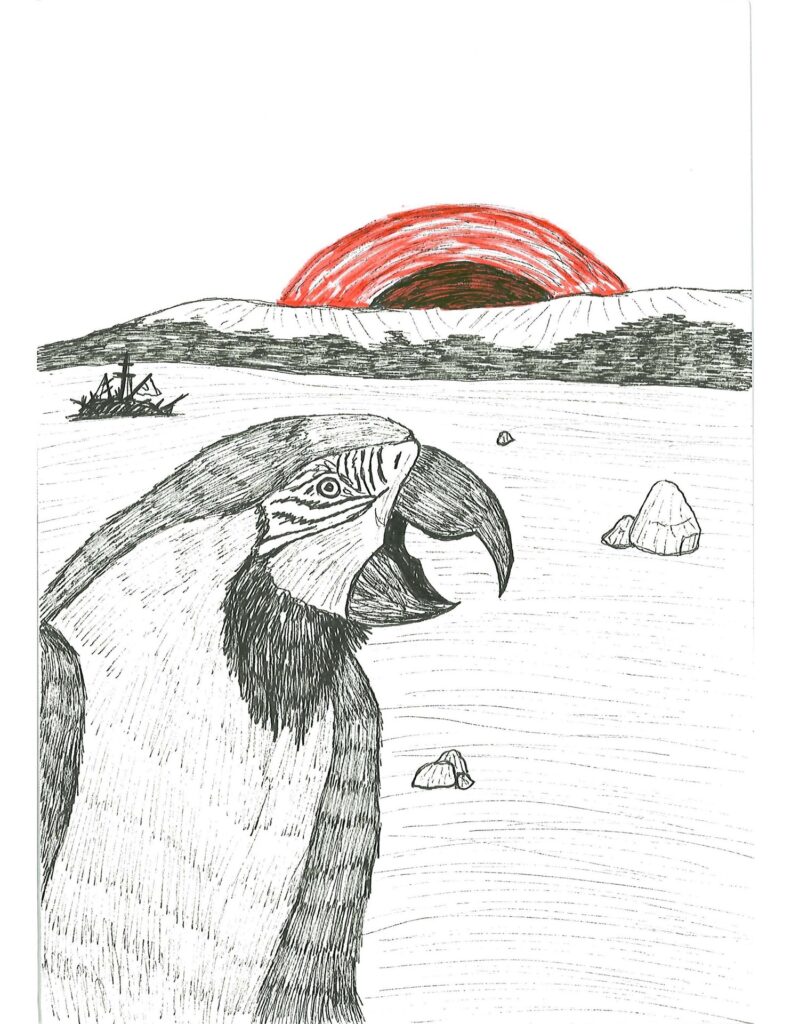

CS: I need to think about that. I would definitely say “Bitterroot,” the piece I just had with Kenyon Review. That sticks out in my mind. “The Young Harris Psalter,” which I did with SplitLip sticks out really heavily in my mind. “Tamar Mepe,” which was with Tampa Review, another one that I really felt combined these things. There’s ways in which I might not make something overtly about the environment, but there will be something in the background that points to it. One thing I really like to do when I’m talking about climate change or talking about comics, where the background is a virulent environment, is to add things being on fire. Really thinking about water. A lot of times I really like having human bodies with animal faces—creating these hybrid bodies, in the style of Donna Haraway or something like that.

I’m also, especially when it comes to disability, very big into leaning into a plastic universe and trying to create this magical realist state of mind, where these ideas, these categories of the body, are no longer relevant or germane. And so bodies can do all sorts of things that you would not think bodies could do in a regular environment. That’s also really important to me, to emphasize the plastic nature of comics as a field, and really trying to go out of my way to not draw very many things being totally realistic. Even in my work right now, I’m doing a lot of gothic magical realism to tell the story. There’s flying whales, and there’s a story about the founding of Nantucket Island. And there’s this whaler, and he’s at sea, and he gets swallowed by a whale. And inside there’s a mermaid and the Devil playing cards for his soul. So I’m able to bring in the Devil, randomly staying in the background for some of the pictures or a mermaid peeping up through the water. Things like that are really important to me.

I’m also very much interested in the grotesque and trying to make grotesque things beautiful and beautiful things grotesque. And shifting those ideas and those categories. And I think for me, as a disabled person, those are terms that I think we sit with a lot. And, especially considering the history of categorizations of disability in the US, there’s something that I really like to screw with and see how I can challenge them in my work. And maybe not in overt ways—maybe just in minor ways, like in winks to the audience. That’s also really important to me when it comes to my creative work.

AA: Mm-hmm. That’s also—what you were stating earlier, with fire in the background and stuff—definitely relates to something I noticed within your work. A lot of the pieces are black and white or muted tones, but when you do include color, it’s often reds and oranges—that kind of color scheme. So, what draws you to this theme? Is that more the climate change impact on the environment—with the fire?

CS: Yeah, I think that’s, in my most distilled form, yes. Because this one being “Oil and Ice,” is ultimately talking about climate change. So there is these weird things—there’s a scarlet macaw in Alaska. And it’s a tropical bird; it’s not supposed to be there. I do like using those reds and oranges to allude to fire. So overall in the graphic novel, the only three colors I use are red, orange, and blue. So there’s the blue when I’m doing the oceans, but then there’s red. Red has a lot of different meanings here—like, one, blood, but also it can be used for fire. I limit myself on my color palette a little bit, more so than I normally would.

When I first started with comics, I was not using color at all. I was very much trying to model myself after Edward Gorey style—strict black and white. But then I came across some Edward Gorey’s where he had used color, and I really liked them. So I guess I became a color minimalist, where when I do have a color I’m including, I do want it to be deliberate. For this dissertation, all in all, it’s mostly black and white, but on pages where there is color, those are the ones that get used.

AA: Okay, interesting! It seems very intentional and symbolic, so it definitely comes through with your pieces. Going off of what you were saying, what are some of your inspirations for your work—what are some general inspirations? What are you generally inspired by?

CS: In terms of artistic inspirations, Edward Gorey’s a big influence. Remedios Varo’s a big influence. Leonora Carrington. Carol Walker is doing really cool stuff. Manuel Lozano, María Izquierdo. I’ve been looking at Mexican surrealists for the past few years, and trying to get into the work that they’re doing. Artistically, I’m also drawing a lot right now from French New Wave films and thinking about images that come out of French New Wave. I kind of want my comics to have a jarring effect, with abrupt stops and odd camera angles and repeat camera angles that are meant to comment something. So those are artistic inspirations.

In terms of cartoonists, very much Lynda Barry, who was my mentor at Wisconsin. I really love her methods of telling stories and drawing stories. I go back to that a lot. Emil Ferris, who wrote My Favorite Thing is Monsters, another really big inspiration. Ebony Flowers, who did Hot Comb, I think she’s doing really great stuff. Isabel Greenberg, who did Encyclopedia of Early Earth. Those are again people I’m really inspired by when it comes to comics and comic storytelling.

In terms of life, what I draw a lot of inspiration from, I really am just kind of an art history nerd. I think that’s what excites me. Every time I go to a museum, I always come out with a beehive of the different things I want to draw. I’ve just been inspired by different styles I’ve seen or different color combinations that I’ve seen.

I’m still kind of riding a high; I went to the Boston Fine Arts Museum for the first time a couple weeks ago, and it’s still really resonating with me. When I was in Wyoming, I was near Grand Teton, and sometimes I would go and sit and draw while I was there. It was more that I liked being outside and the weather was pleasant; I’m not really a big “draw things from life” kind of person. But it can be really nice to find a cool place with a nice climate to just go outside and be present in nature and draw.

AA: Yeah, cool. I definitely find that, getting inspiration from other art—and museums and stuff. So on your website, it states that you received your MA in Gender Studies at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Could you discuss how these studies in that discipline present themselves in your work?

CS: That’s a great question! My first ever long-length graphic novel I did was actually my Master’s thesis at Madison, which was about disability and gender in the school house blizzard of 1888, which impacted these three teachers. So how categories of disability and gender were constructed in that disaster. I was able to turn that into a comic. So, again, I hold that in my core—that feminist lit comics are a feminist research method. A lot of feminist researchers bring that into the conversation—drawing an interview with somebody and showing them what they described to you. And then giving them editorial control to say, “No, it looked more like that” or “It looked more like that.” I think that’s all really important in terms of humanizing research and humanizing experiences that humans have that they’re trying to convey through research. So that’s always at the corner of my work, because that’s what I’m trying to do now, as a disabilities studies scholar, is really bring in that category of disability.

It’s also interesting because I have really had to, with this research, dig deeper into questions of masculinity and masculinity studies that I had maybe not paid as much attention to as I should have before. But that’s been really interesting. So today, for example, I was reading an article on masculinity in Jeffersonian democracy, and that’s having to show up in my work now. Because right now, when I’m talking about whale ships, there just weren’t as many women on board because typically women would have been viewed as bad luck or women wouldn’t be allowed for whatever reason. So that’s something I’m having to think about and sit with. That’s always in the background of my work.

And again, a lot of the things that I write about deal with researching feminist studies. Like the one “Bitterroot” comic that was just published is about how I was working as an education outreach coordinator for a project about Radcliffe Hall and Una Troubridge and just the frustration that came out of researching these deeply frustrating and problematic women who also were pioneers, in a way, and pioneers for queer rights in a way and having to sit with those nuances and how frustrating that can be.

I have a long-term goal—I’ve not started it yet—of doing a comic about Betty Friedan being trapped in this bardo where she has to watch early 2000’s reality TV shows that involve a man taking a wife from a pool of twelve applicants, and it all delves into nonsense and chaos. So topics like that are still really important to me and show up in my work a lot. I began a cartoonist by thinking of it as a feminist research method and a justice-based research method. It’s something that’s very important to my work and something that I still hold onto as I continue this process.

AA: That’s interesting. I’ve never really thought about it that way—the justice research method—because, like you said earlier, it can definitely being a representation of how somebody perceives their world. That’s a really cool way of viewing it. I have one last question. You kind of touched on this earlier, but many of your pieces have this central character that is often human-like and then has animal parts, like maybe an animal face. Could you comment on this theme and explain the intentions behind this?

CS: I don’t know—I like the magical realist element of it. I find it surreal and jarring and—I don’t want to say horror—but I’m kind of trying to lean into eco-horror a little bit. I think these unsettling images are important if you’re trying to tell a story that is deeply unsettling, but that I think a lot of people just regulate to a part of history. They think of whaling as being sad, but also what’s happening right now with climate change and the fact that we’re killing more whales than we did in the heyday of Yankee whaling, with ship collisions. People treat it with this aura of finality—that it’s not something to be distressed about.

Part of it is that I like disrupting the idea of the body being a single, static thing or trying to draw a person that looks like “an ideal person.” I do like this mix and match of human bodies and animal heads and things like that in order to—one, comment on how we think about bodies and what we think of as “correct” and “incorrect” bodies. Also, to look at these interactions between humans and animals—that we’re not always quite sure what to do with. These interactions between humans and whales were usually pretty violent, and it’s the same thing with humans and sharks. But that’s because humans are going into these animals’ habitats and trying to kill them, so of course they’re going to be violent. So if you don’t want to be crushed by a sperm whale, don’t go hunt sperm whales. If you don’t want to get bitten by a shark, don’t go into shark-infested waters to deliver a bomb, you know, like in WWII. It’s that kind of sight of these human-animal interactions that sometimes can end up being violent that I’m just really fixated on right now. I think that’s part of it.

I also like the idea of eco-horror being a genre in and of itself. These elements of horror existing visually in a place where slow violence is taking place against humans to get people thinking about that is really important to me and my work. And for a very long time, I’ve always been fascinated by the interactions between humans and animals. So I think that’s a very long-winded summary of where my mind is when I go in with this human-hybrid approach. Because I want it to be unsettling, and I want people to be disturbed by it. And I also want to include something in the background that people would find unsettling or disturbing. In one, a man’s face is a stingray, and behind him is an oil freighter. So thinking about what is really terrifying about this concept. That’s just a very long-winded overview of why I have that as a motif that occurs in a lot of my work.

AA: That just got me thinking actually about how a lot of people—or at least an issue with some people—is that humans will often have more empathy for animals that get hurt than other humans that get hurt. So that’s an interesting way of combining the two that I didn’t think of before this.

CS: I think one of the things… I’m hesitant when I talk about empathy because it’s a term I don’t know how valuable I find it is—in the sense of the idea of feeling something for someone is perceived of as being enough. But I’ve done a lot of research into why people get more sad when animals die than humans. One is that it’s got to be a weird deflection or self-delusion technique to help people emotionally distance themselves from that horror of human suffering.

And also, I think my work is drawing on the histories of colonization and that part of the animal compassion movement had its roots in colonization. Like, “We’re going to the Philippines to ban cock fighting because that’s such a horrible practice.” And these people mistreat whales, and we would never. And this whole gospel of kindness towards animals is kind of rooted in this idea of control and dominance that I find uncomfortable. And again, I’m vegetarian, and I’ve always really liked animals, and I also, until recently, hadn’t thought about the number of times I’ve heard people say that they’re always more sad in a movie when a horse dies than a human. And I’m like, “That is a very peculiar thing to say. You can be sad about both.” And there’s this personification of animals being totally innocent, and this personification of all humans as being innately evil… It’s very strange to watch War Horse, and you walk away feeling sad for the horse, you know? Like, you just watched sixteen-year-old German soldiers get shot for abandonment. It’s just a very… It’s not necessarily something I blame people for, but I do think it’s something that’s imbued in a lot of white dominant culture—that people have not fully reckoned with yet.

AA: Yeah, very true!