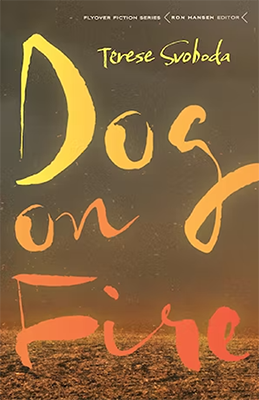

At turns hilariously absurd and gut-wrenchingly heartfelt, Terese Svoboda’s Dog on Fire, published by the University of Nebraska Press, defies genre. Svoboda juggles comedy, mystery, tragedy, horror—and masters them all. The book follows a recently-divorced woman grieving the mysterious and early death of her estranged brother. Her unusual circumstances lead her to move back to her small Midwestern home town, where everything and anything she does creates ripples of rumor. There, she confronts perilous Halloween parties, Jell-O inventions, guns, grave-diggers, and, of course, dogs on fire.

With rich prose more reminiscent of poetry, Svoboda’s characters burst from the page. One “harbors streaks of shyness the way bacon is streaked, between boldnesses,” while another drags “nothing out of this primordial water and [tries] to turn it inside out, into a something.” They’re as compelling and unforgettable as they are human.

At its heart, though, Dog on Fire is about two women struggling to find themselves—and overcome their mistrust of each other—when someone they love has died and their worlds seem to be falling apart.

Tense, poignant, urgent, and at times scathing, with Dog on Fire Svoboda has performed the astonishing dual feat of writing what could be called a contemporary Dust Bowl Gothic novel and creating a pitch-perfect work depicting the feelings of rage, grief, and isolation that come with losing a loved one. Without a doubt, Dog on Fire is Svoboda at her finest.

Rone Shavers, author of Silverfish

Terese Svoboda has written 20 books—including Cannibal, which won the Bobst Prize and the Great Lakes Colleges Association First Fiction Prize, and Tin God, which was a John Gardner Fiction book Award Finalist. She has won the Iowa Prize for poetry, an NEH grant for translation, the Graywolf Nonfiction Prize, a Jerome Foundation prize for video, the O. Henry award for the short story, and a Pushcart Prize for the essay. She is a three time winner of the New York Foundation for the Arts fellowship, and has been awarded Headlands, James Merrill, Hawthornden, Hermitage, Yaddo, McDowell, and Bellagio residencies. To learn more, visit her website.

Dog on Fire is a blisteringly perceptive novel about grief, secrets, and the intractability of love. The mysteries surrounding one man’s death, narrated alternately by his sister and his lover, yield no easy answers in this haunting and darkly witty reckoning.

Dawn Raffel, author of Boundless as the Sky

Dog on Fire will be released March, 2023, by the University of Nebraska Press. Pre-order it here.

We’re also very excited to share an interview that dives deeper into Terese Svoboda’s book. This interview was conducted via email by our Blog Editor, Brennie Shoup.

Brennie Shoup: In your novel, only one character—Aphra—is named. The rest are given titles or referred to by

their familial role. Could you discuss why you chose to do this?

Terese Svoboda: I like to think by not naming the characters, the reader identifies more quickly with them, has no Jane

or Edward that he despises that might stand in the way of relating to the character’s predicament. Besides, naming suggests a familiarity that isn’t there, especially at the beginning of a book. You’ve just been introduced and you’re plunged into a narrative-of-no-return? There’s resistance. Aphra is named so as not to confuse the two female voices but I could have done without hers too—my fifth book of fiction, Pirate Talk or Mermalade, uses only unnamed voices in the 18th century—but to police that is a lot of work, and too arch for Dog on Fire.

BS: What were your inspirations for this work? Do you have any other authors or creators you look to when you write?

TS: A dead brother was the main inspiration, and how his epilepsy and death affected the (much camouflaged but emotionally true-in-the-book) family. I’m originally (and still) a poet and that’s where most of my influences lie, where words and emotion drive the narrative as much as plot—with poetry’s emphasis on accuracy and conciseness thrown in. I’ve always loved Russell Edson’s surreal prose poems. In prose, I would’ve liked to have written Self-Portrait in Green by the French writer Marie Ndiaye.

BS: Many of the themes in this book revolve around family, gender, love, hate, and abuse. Could you talk about what drew you to these themes? Did you have a hard time interweaving these themes, or did they seem naturally drawn to each other when you wrote?

TS: The world of family, gender, love, hate, and abuse—that’s the stuff of most novels! And you really can’t have one without the other. But I never think about themes. That’s for you, the critic. The sentence is my guiding principle, and seldom do I imagine much beyond it. If a theme coalesces around a group of sentences, that’s great. Words pack so much connotation that it’s enough to get out a sentence, let alone a theme.

BS: In this novel, you don’t use quotation marks for dialogue. You also go between Aphra’s point of view and our main narrator’s point of view. How did you decide to write the book in this way?

TS: I never use quotations marks for dialogue in my fiction. I don’t like to clutter up the page with a lot of symbols—they’re like cymbals to me, clanging away to remind the reader, This is speech, when sometimes speech is half-imagined. A writer should be deft enough to manipulate the syntax to show who’s speaking.

Aphra’s point of view came late in the book’s revisions, in response to an excellent reader’s review. I’m hoping Aphra offers additional information and complexity to the plot, and another point of view makes the narrator’s perceptions more credible. I feared that a new reader might not be able to shake off pre-conceived notions about someone of a certain size without listening to her side of the story.

BS: Do you have any novels or other projects you’re working on?

TS: My eighth book of fiction, Roxy and Coco, about two harpies-turned-social-workers who now and then off abusive parents, will be published by West Virginia University Press next spring—and I’ve just won a prize (I’m not supposed to say which for another month!) for a collection of stories called The Long Swim that will also come out next spring. My second memoir, Hitler and My Mother-in-Law is, at the moment, longlisted for possible publication. When it rains, as in NZ, it pours. I am particularly grateful to university presses, especially the University of Nebraska Press that has published two of my novels and reprinted another two.

But stand back! My drawers are deep—I have two more collections and three more novels needing homes, and I’m very excited about a new novel manuscript I’m working on called Goose Girl.