Jeff Fearnside is the author of two full-length books and two chapbooks. His poems have appeared in numerous literary journals and anthologies, including The Paris Review, Los Angeles Review, Valparaiso Poetry Review, and Forest Under Story: Creative Inquiry in an Old-Growth Forest (University of Washington Press). Honors for his work include writing residencies at the Bernheim Arboretum and Research Forest and the H. J. Andrews Experimental Forest, the Peace Corps Writers Poetry Award, and an Oregon Arts Commission Individual Artist Fellowship. He has taught writing and literature in Kazakhstan and at various institutions in the U.S., currently Oregon State University. Read his most recent book.

Ashley Goodwin: What inspired you to write “The Way of the Seeded Earth?”

Jeff Fearnside: Oregon’s Coast Range mountains are just minutes from my home, and my wife and I have spent countless days exploring them. One of the beautiful and ubiquitous creatures living in this range is the salamander, in particular, the rough-skinned newt. I’ve had a chance to closely observe them on numerous occasions in all seasons, and the poem came out of those observations. Its title comes from the title of a book by Joseph Campbell, and while the poem isn’t directly related to that book in any way, the title suggests what I wanted to convey, what salamanders so strongly embody: This is how the world seeds itself. This is how life moves through life.

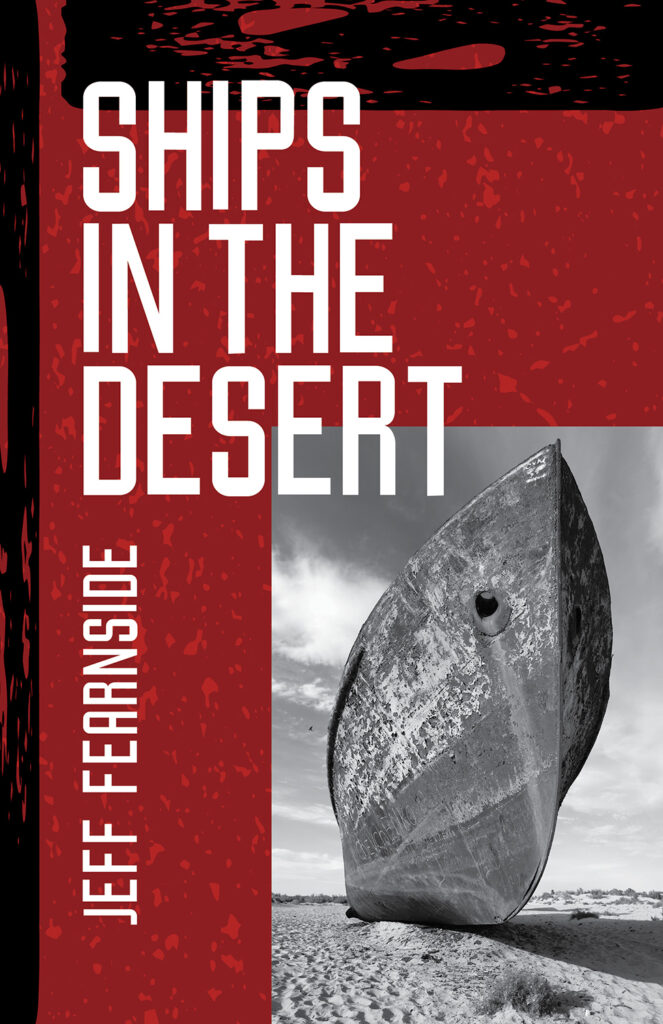

AG: Your most recent book, Ships in the Desert, recently won the Foreword Indies book of the year award and the Eric Hoffer Book Award. Could you describe the book for people who are just hearing about it?

JF: I’m happy to say it also just won an Independent Author Network Book of the Year Award! It’s a collection of linked essays about my four years of living in Kazakhstan, so it’s very much a personal story. It’s also about the environmental challenges we face today, particularly in regards to water, as explored through a trip to the dying Aral Sea in Central Asia. Finally, it’s about culture, the differences between East and West, and how we might better understand each other. So anyone with an interest in the environment or other parts of the world should find something of value in it. It was definitely a passion project for me.

AG: What is your process for composing?

JF: It depends entirely on the piece. I believe process is dictated by the particular qualities of each piece, and that my job as a writer is to discover what those particulars are. So writing for me is a process of exploration. Sometimes, right from the beginning, I’ll have a very clear idea of what the piece is or seems to be, while sometimes I’ll begin with nothing but a single phrase or idea in mind. It doesn’t matter. Once I start writing, I let the words lead me. I work very intuitively while drafting. I bring my knowledge of craft into the process during editing, though the goal is still the same: discover what the piece wants to be and help it become its best.

AG: What made you want to become a writer?

JF: Reading. I loved reading as a kid, and I wanted to do what the authors I loved were doing: to make the kind of magic I felt when I read their books. It really was that simple. Of course, I grew older, discovered all kinds of different writing from all over the world, critiqued it, came to understand the technical aspects of it. All of that was good. But I still feel my writing is best when I don’t overthink the technical aspects of it and simply approach my work with a child’s sense of wonder. That’s what as an adult keeps me writing.

AG: What advice would you give to young writers?

JF: Read, read, read, and write, write, write. Nurture your imagination. Find inspiration everywhere, not just in your favorite books but also in the ones you think you don’t like. Devour it all. And don’t forget to live. Allow yourself to fully feel your experiences, both positive and unpleasant, as well as everything in-between. Come to know yourself through your life and writing. Don’t be afraid to make mistakes. Be human.

AG: What are your favorite books to read?

JF: I love just about everything, from realism to magical realism, from the dead serious to the surrealist, the satirical, the humorous, even so-called genre writing like the mysteries and science fiction that first inspired me when I was a boy. I love fiction, poetry, nonfiction, drama. I’m one of those strange people who reads Shakespeare for pleasure! I’m an omnivorous bibliophile. A bibliovore. But like most people nowadays, I’m busy, and I’m a slow, careful reader—the more I like a book, the slower I read. So simply as a practical matter, I most often gravitate to story and poem collections, books I can savor in parts even if I don’t have a lot of time to read. I really don’t understand why short stories are supposedly such a hard sell. Given how crazy busy everyone is today, I would think that short stories would be more popular than ever! And what can one say about poetry? Good poetry is like water or blood. It’s necessary to life.

More info: http://www.jeff-fearnside.com/

Jebel Irhoud

This is where we came from.

This is where we lived,

in a Moroccan cave

315,000 years

before Morocco,

before language and time

as we know it.

We had come far already

from the east,

spreading across a continent

with stone tools,

curiosity and cunning.

The songs in those bones

still play in ours,

whistling through marrow.

The dances they danced

still coil in our muscles,

sprung free

whenever we move

from our centers.

Pick up a piece of flint.

Do you remember

the scraping of tendons,

the scuff of hide?

Something calls you

to test the keen edges,

turn the stone over and over

in your palm.

Build a wood fire.

Contemplate the stars.

Paint with your fingers,

pull weeds,

feel the rasp of grass seed

against flesh.

Seek shelter from a storm

in any natural place.

Turn your face upward,

lick the drops rolling

off your lips.

It’s the same water

of the first rains

and rivers and lakes.

That prick of blood

where you got snagged in the wood

tangs of the same salt

of the first oceans.

The Way of the Seeded Earth

We humans think we have it rough.

Try mating underwater

with two—or four or six—

would-be suitors cutting in

on your amplexus.

But for those

ultra-sticky nuptial pads,

you’d be pulled apart.

It can take hours. The mass

of bodies rolls and clutches

in a shallow pool, tails like

streamers or spiral arms

of galaxies in the cosmic amnion,

like a ball of baby snakes.

On land they move

separately, somnolently,

each step a lesson

in what it means to stake a claim

to one’s terrestrial heritage.

Yet two salamanders

left unharried in wedded embrace

swim, turn and dive to bottom

as a single body,

a single current

in all that surrounds them.

Speaking with the Dead

The dead don’t speak

only to the dead,

though they prefer it.

To walk in nature

is to initiate a séance.

Spirits knock on wood,

rattle vines,

raise the forest floor

and speak in whispers

along creekbeds

and in drainages

that channel warm drafts up

and cold drafts down.

The coldest lie stagnant

in hollows.

You will hear

most clearly there.

To speak with the dead,

go to the low places.

Let them approach

and then ask your questions.

Only know this: the answers

may come from anywhere.

Elk Hotel

We didn’t see them, but we knew they were

somewhere near, hiding from the day and us

in the darkest part of the woods. Their trails

run through this place: to shelter, to water.

Hoof prints lie stamped in mud, while black droppings

like breadcrumbs occasionally offer

paths our muskier selves long to follow.

We’ve seen them before, gathering to feed

at dusk at the edge of a nearby field

redolent with the succulent flowers

they savor while bathing in the dying

light, the cool air, the comfort of safety.

In our refuge from coronavirus

we often come here to walk out all that

we do not wish to talk or think about.

We’ve forgotten what it means to be free.

Each time, we’re amazed that the woods doesn’t

have to wear a mask, that the sky can breathe

so heavily upon us without guilt.

We know the herd has visited because

just behind the thick hedge of blackberries

in the lowest point of the depression

stands the grand Elk Hotel. The matted grass

details reservations for two dozen.

It’s all about location—privacy

assured, amenities accessible

within the stretch of a sinewed foreleg.

I can imagine them in swimming trunks,

lolling at the edge of the slough, talking

of the news of the day, shaking their large

antlered heads while sipping wild blackberry

cocktails and wondering just what is so

especial about those animals with

their shrill protestations and smoking guns.

Belonging

On a log in the creek

a hollowed-out knot

where a limb once reached

to the sky. In the knot

pebbles, pale and smooth,

like a clutch of hummingbird eggs

on a bed of creek sand.

Tiny sprouts of green

grow between the pebbles.

Cottonwood seeds like down feathers

rest comfortably, protected

in the log-walled hollow,

the entire space the size

of a large chicken’s egg,

or the polished jade oval

we saw in the gem shop

while searching for garden rocks.

Your hand was a gemstone

or an egg

in my hand

even after all these years.

- An Interview with Jeff Fearnside - January 10, 2024

- An Interview with Lauren Tess - November 22, 2023