Guest Posts

Posts written by people not currently on the SR staff.

“Do Robots Make Good Poets?” Let’s Discuss.

They cannot evoke a poet’s self, but they can sometimes come up with useful lines.

Like many writers and teachers, I feel the gathering threat of machine-written literature. In the old days of computers, there used to be a saying, “Garbage in, garbage out.” Today, into the maw of large language models, some garbage no doubt goes. But these large language models are also fed, as I understand it, all the text that exists on the internet and that includes the great works of world literature (though maybe not very recent works). It is becoming more common to allow these models or chatbots to write essays, analyses, business plans, and the like. As a teacher of poetry writing, I wanted to see how these bots might operate in the creative-writing classroom. I wanted to find out if robots made good poets.

To attempt to answer this, I created an exercise for my Summer 2023 Drexel University poetry writing class to see how and how well ChatGPT generated poems. The exercise comprised several steps. Students first had to engineer a prompt that included a topic, a mood, and some key words. That took some thinking and attention to self. Next, students told their chatbots to produce a poem based on their engineered prompts. The bots produced the poems in fifteen seconds. Following this, students shared the bot poems out loud in class and posted them on our teaching platform (Blackboard), and we workshopped the robot poems. Finally, the students had to harvest from their robot poems any usable lines and make them part of their own follow-up poem. As a means of attribution, the students were required to underline the robot-written lines they added to their self-written follow-up poems. (It does feel weird to use the term self-written).

Occasionally the students found some strong and usable lines in the robot poems. More often than not, however, the students condemned the robot poems as soulless and rote imitations of verse. Not only were the students vehement and harsh critics of the robot poems, they were enthusiastic about each other’s real voices, praising each other’s follow-up poems for their sincerity and heart. I was very encouraged by the students’ overall negative attitude to the chatbot poems. As much as I hate to say this, I was a little less harsh than the students about some of the AI poems.

The students in this class were sophomores on up and came from a wide variety of majors. No one was required to participate in this exercise. Three students did opt out of the exercise: a philosophy major, a computer science major, and an English major.

Of course, the robots were good at spelling, mechanics, and standard English grammar. This was a benefit to all, especially the English language learners in the class. I appreciated the clean copy as I did not have to pinpoint glitches in proofreading. Almost always when the tool saw the term “poem” in the prompt, it generated a rhymed poem even when the student’s prompt specified an unrhymed poem. Once in a while, the bots committed the classic error of sacrificing meaning or correct usage in the service of rhyme. Sometimes I could detect the influence of English and American poets from the tradition in the AI poems even when the students did not request a poem “in the style of.”

I present here a selection of student-engineered prompts, the raw robot poems, students’ own poems connected with the exercise, workshop comments about the robot poems, and a few other observations. Finally, I include some of my students’ overall comments on the exercise and some of my own opinions about the future of AI-generated literature. All the students quoted and named here gave me permission to use their work and their names.

The precursor prompt

Before I began the more creative part of the exercise, I had all the participating students ask ChatGPT to write an unrhymed ten-line poem from a prompt I engineered. The bot was to write a poem about a man named Sam who encounters a wolf while hiking in the woods, incorporating the words “gray,” “the smell of green weeds,” “teeth,” “gun,” “afraid,” “run,” “yell,” “twilight,” “safe.” All the robot poems were different!

Samples from the multi-step exercise

English major Diamond Warney offered ChatGPT this prompt:

No rhyme scheme. Ominous and foreboding mood – “Something is coming. Use the verbs ‘devour,’ ‘drown,’ ‘mourn,’ ‘sleep’ and ‘drive.’ Use the adjectives ‘godly,’ ‘delicious,’ ‘heavenly,’ and ‘pungent.’ Use elements of different religions and faiths. Use the words ‘purple,’ ‘garlic,’ and ‘hospital.’ Use the phrase, ‘Richie, don’t be late for dinner.’” Diamond underlined the phrases in the raw ChatGPT poem that she included in her original poem, and she underlined those raw phrases (or their revisions) in her follow-up poem.

Here is the raw ChatGPT poem generated from Diamond’s prompt:

untitled In shadows cast by gods of old and new, An ominous veil, foreboding, weaves its view, As whispers 'cross diverse faiths, they fly, The harbinger of change, impending nigh. Devouring stars, a cosmic tempest looms, Religions' ancient scripts in heavenly tombs, They drown in sacred waters, souls in mourn, While deities in slumber, await their cosmic turn. From east to west, the chariots of fate do drive, A pungent scent of garlic, offerings alive, Yet Richie, don't be late for dinner, pray, For in this mystic hour, worlds may fall away. Purple shrouds the horizon, darkness to distill, A hospital for hope, a reckoning, and will.

Of this poem, Diamond remarked, “The first and last lines are interesting and could be reworked and added to a better work. I also like the line, ‘Richie, don’t be late for dinner, pray.’ I didn’t think about praying before meals when I wrote the prompts. I think ChatGPT could be used to connect ideas you had but didn’t realize were related. The bot didn’t pick up on tone and literally used the words in the poem, but there are some ominous images in here like the mass of purple on the horizon. The bot also connected some of the words that I used in the prompt, like garlic and pungent.”

A few observations from me as instructor:

My take here is that the AI knew many stock phrases about spirituality and the cosmos and churned them into a rhymed sonnet even though Diamond didn’t ask for a sonnet. The program mostly used Diamond’s key words in the order she listed them in her prompt. It did not use the word “godly,” but did use the word “god.”

Below is the follow-up poem Diamond created incorporating some AI-generated phrases. These are underlined.

Kitchen Sink By Diamond Warney Babies left behind by gods of yesterday and today at fire stations, on doorsteps, in pews reaching out plump hands trying to catch the stars. The only sign the gods were ever there. My mother left me in a gas station. I drank warm fuel from the pumps and got high on the smell of Black & Mild’s. In death, our atoms spread to become tiny pieces of everything. We are beautiful and cosmic. We are ourselves again. You said you knew I was trouble from the way I drive, with my head out the window devouring stars and flies. No one taught me to stay inside the lines So drown me in the sacred waters your mother bathed you in before you grew out of the kitchen sink. Maybe then, I’ll know how to be loved. Maybe then, I will be cleansed.

A few observations from me as instructor:

Diamond’s new poem cries out in sympathy for discarded and abandoned children whose only solace, sadly, comes from a mysterious connection to the universe. Then she shifts to a literary speaker who is an outsider, a foundling left at a gas station and who knows the world from gas station odors, such as the smell of tobacco and gasoline. The voice then speaks as an adult who still sees herself as an outsider evoked in part by the image of her dangerously driving with her head out of a car window.

Aliyadeth Griffiths, an English major, did a turn-about. First, she wrote her own poem on the theme of striving, critically assessing the self in the mirror, and incorporating the sentences, “Be more. Do more.”

Are You Satisfied Yet? By Aliyadeth Griffiths As I look at myself in the mirror, Reflections of all I could be watch me intently, Their eyes gazing with avid curiosity. They haunt the bathroom mirror, With a sinister smile plastered across their face. Like lurking shadows, they taunt me. “Be more. Do more.” They breathe against my neck. In return, I stare at my decaying appearance. My skin, fractured and pale, crumbling under my touch, The dark circles underneath my eyes rise as I try to smile, My hands trembling from fatigue. “Be more. Do more.” They whisper again, their cries louder this time, The voices of the expectations echoing on the reflection, Reminding me that I am meant to be nothing but perfection. The bones in my body creak loudly as I stand, Aching and frail, I stare at all the work that haunts me in my sleep. I can always do more. I can always be more. I can always work harder than I ever have before. The voices in the mirror seem pleased by my response, As I turn away from my reflection, My body collapsing on the floor.

Aliyadeth’s own poem speaks through graphic and even ghoulish imagery that invokes feelings of self-criticism and self-condemnation, and it includes a strong charge to try even harder to achieve better things. There emerges an interesting dialogue with the self in the mirror.

After composing her own poem, Aliyadeth provided this prompt to ChatGPT. “Write a horror 22-line poem about being a burnout high achiever, including the phrase, ‘Be more. Do more.'” She also asked the bot to create a title. Here is what the robot wrote.

Whispers of the Abyss: The Burnout's Lament In shadows cast by fractured dreams, I dwell, A burnout high achiever's cursed spell, Once driven by the whispers of success's lore, Now trapped within a labyrinth of endless chore. Be more. Do more. The mantra drilled in bone, A relentless pursuit, a heart turned stone, I climbed the pinnacles of acclaim and might, Only to find the abyss in that blinding light. Frenzied steps echoed, accolades in tow, Yet the void within grew with every glow, A phantom grin masked the wearied soul, As I danced on embers, an unholy toll. Be more. Do more. The voices never cease, A crescendo of torment, a maddening peace, Shadows stretch, merging with fractured mind, In this twisted symphony, where hopes unwind. Reflections leer, distorted and askew, A burnout's tale, a nightmare woven true, Haunted by echoes of an insatiable roar, Be more. Do more. Until you're no more.

Here are peer comments on Aliyadeth’s two poems.

From Maura Mealy, a psychology major:

As always, your work is stellar! As much as I hate to say, I enjoyed an aspect of the bot poem, the repetition in the “Be more. Do More.” The lines were surprising from ChatGPT, but it was part of your original prompt! Your actual poem blew the AI out of the water. The actual narrative and story felt realistic and relatable. The repetition in this felt much more natural and flowed better in the poem, and it was just, in general, more of an enjoyable read. The AI gets bogged down in trying to use fanciful words while you actually utilize descriptors to move the poem along. Great job, as always!!

From Zakee Aleem, a finance major:

The poem drafted by AI was surpringly good even tho still void of so much emotion or even a setting. I think it somehow works because the prompt lends itself to a cold poem void of love and affection. Your poem is much more emotional and I can really place myself in this poem much easier. Great work!

A few observations from me as instructor:

In the bot-generated version, I heard echoes of Byron, Shelley, and Poe. The AI poem had a drumming rhythm and remorseful tone that suited the subject and the injunction to “Be more. Do more.”

Every so often, the bot would come up with a very sophisticated line. Malachi Solomon, a general studies major, told the bot to write an unrhymed sad poem with these terms: “kick, punch, stupid, good, honest, helpful, caring, fragrant, bang, uncle.” Although the AI poem was filled with the stock observations and persistent rhyme, the robot did come up with one terrific example of anthimeria (use of one part of speech as if it were another): “A kick to the heart, a punch in the think.” “A punch in the think.” What a great phrase. It evokes a harsh and shocking assault to the mind. While Malachi did not decide to use that phrase in his follow-up poem, I have to give AI some props for generating it. Makes me wonder what was going on in the think of the program.

How beneficial is ChatGPT to you as a poet?

I posed this question to the class, and here are some of the students’ responses.

From Anna Bokarev, and English and writing major:

To me personally, I don’t think ChatGPT will be all that beneficial. In fact, I found it really difficult to workshop the poem that ChatGPT spit out for me. It didn’t really have a tone or voice, and workshopping that into the poem required me to tear it apart and delete most of it. I also wasn’t the biggest fan of the phrases it used. Some of them were pretty interesting, but they were all so surface level that I couldn’t really incorporate them into a narrative-styled poem. ChatGPT was doing a lot of telling but not a lot of showing.

I also just think reading the work and finding inspiration from real writers is a far better way to do it than consulting ChatGPT. There’s voice and passion in the work of human writers, which I believe is what ultimately inspires a writer. For now, I’d rather avoid the tool at all costs. It seemed to make my writing process more difficult and dull.

From Grace Dhankhar, a computer science major. Grace was one of the students who opted out of the ChatGPT experiment:

Personally, I am very against the use of AI tools like ChatGPT, and I have very strong feelings about it, but I understand that people are going to use it regardless of my opinion of it. With that being said, if people are going to use it, I think that it would be a cool tool if someone wanted to find a new way to say something or a new phrase, since some of the phrases the AI came up with were sort of eloquent, but I would absolutely never rely on it to create anything actually creative. With all of the examples shown in class, the human poem or revision of the poem is so much better and less nonsensical since the AI couldn’t really put together coherent thoughts together.

From Aliyadeth Griffiths, English major:

For me, ChatGPT has always been more hindering than helpful, especially when it comes to the writing process. I find that reading the bot’s writing before coming up with my own often confuses me, because of its excessive eloquence, along with feeling as if I can’t use any idea the bot might’ve come up with because of the questionable ethics. I also don’t particularly enjoy using even one line from it, as I feel like I’m stealing from the authors the bot has been fed.

While I am not completely against ever using AI (I feel like there is no point in being so against it—this is the way technology moving forward, and there’s no point in trying to fight it; especially when it is being used so often, by so many people and organizations), but I don’t particularly enjoy it. It feels wrong, as we can’t make sure which of these authors would actually be okay with their work being used this way. While I do think it’s crazy how far technology has come (for better or for worse!), it feels wrong to use it, especially with the writers’ strike going on as writers are not being paid enough to make a living.

[Note: The Writers Guild of America strike, which began on May 2, 2023, was still going as of the writing of this post in late August 2023.]

From Maura Mealy, psychology major:

I think it’s essential to make the distinction that ChatGPT/AI models like it should be used as tools and not solutions. We talked in class about how these models are fed information and language from great literary sources, like Poe or Wordsworth or whomever, but anyone can feed data into these models. You can tell the AI 2+2=100 enough times, and it’ll believe it. When using it to generate ideas or references, it’s super critical to fact-check them, especially when using it in a creative sense. We saw some fascinating lines come out of the AI poems from the class exercise, some of which didn’t totally suck. While the chance the AI-generated those lines entirely on its own is high, I still feel the need to do a quick Google search to check if these “good lines” were plagiarized material/lines someone else had fed into the machine.

In the context of writing poetry, this is not a useless tool. It can come up with pretty words/fancy phrases if you are looking for some old-school inspiration. The narratives it generates are straightforward and basic, with surface-level meaning. I feel like most poets seek a deeper meaning behind the pretty imagery used, which the bot just couldn’t create.

From a majority of students in the class:

The class suggested that I try this exercise next year because they said that the bots will change and people’s perceptions about large language models and other forms of AI will also change.

Some perspectives on the future of writing and AI:

The students’ pushback against the robots and their observations on the dangers of AI gave me faith in the value of human sensitivity and creativity. But the exercise also made me fearful. ChatGPT did occasionally come up with good lines. The large language model was built on the DNA of the literary tradition, and thus was more learned that the students or me or anyone. It suffered no gaps in education or memory. True self-expression grows out of subjectivity and that oddness that puts the stamp of individuality on a writer’s voice. Can a machine ever duplicate that individuality, or if not duplicate it create a new individuality altogether?

I am concerned, as many others are, that facile AI creations might dominate the arts or “popular culture” (whatever that is). Will the bot scribes, in time, coax us into accepting their recombinations and mutations of preexisting literature, no matter how elegant and respectful of the human condition that preexisting literature is? Will AI-generated literature become so widespread that we accept its verbiage as literature? Or, more concerningly, might AI create new believable individualities that produce real poetry?

This is not the first time that human ingenuity has unleashed great powers for human benefit or harm. Consider the printing press, the radio, the telephone, the internet. Think of the atomic bomb, gain-of-function viruses, human-caused climate change. Then think of increased freedom of expression, nuclear nonproliferation treaties, laws (heeded or not) against chemical and biological warfare, medical progress, the fight against global warming. Reflect on how effective AI already is for speeding along propaganda and untruth. In the midst of doomsday threats, the prospect of AI-created poetry seems barely worth the worry. Depending on how seriously AI dominates, poets and writers can resort to samizdat. It would not be the first time writers had to do that.

You can read Lynn Levin’s poem, “Sam Shipper and the Rock: Fiction Writing 101” in Superstition Review‘s Issue 6. Additionally, her guest post, “Beloved, Open Your Door” can be read on our blog.

An Interview with E Townsend

This is the Perfect Song for a Forever 21 Store a Decade Ago

After “Men On The Moon,” Chelsea Cutler

We put men on the moon / But I still don’t know how to get to you

We lose each other in between curated bohemian, glitzy, casual rooms in Forever 21, and I know to find you far away from the plus-size section, where I currently am, comforted by the fact this is the first place in my life I can shop for clothes that fit and are kinda sorta actually cool. Lorde blares in the speakers It feels so scary getting old and I need to remember to look up this song later to share with you. I search like a serpent between racks, my attention shifting to hundreds of different clothing styles, trying hard to make a beeline to the dressing rooms. You laugh when you spot a pile of long-sleeve shirts in my arm.

“Knew it would take you a while to find me.”

I don’t know when I’m going to lose you for good.

And now all I can do / Is wait for you to come down

I am so sorry for all the times I scared you. Dropping suicidal threats before lunch in seventh grade, hiding in the science classroom to avoid you. All to get attention that I shouldn’t have fought for, everyone has a life and I need to be better at allowing breathing room. You’re very brave for putting up with this shit. We’re too young, we should be talking about boys, not my frequently imagined funeral.

Years later I do it again to someone else, I hurt them as hard as I hurt you, and I can only see your face in place of theirs, disapproving and reddened, oceans splitting into two. I am always above you when I should’ve been below.

Our friends don’t understand the delicacy of this buoyancy. How I bounce between girls to fill a savior-complex void, knowing I would go back to you, knowing they couldn’t save me well enough to feel like it is enough. Nothing is enough.

We built weapons of war / But I’m out of bullets to fire

It takes three years of college to move on, write a mean essay self-victimizing my depression and our friendship. It takes another three years to write a new essay and realize you were the victim from my suffocation. Bitterness burrows deep when I read that old piece—I was not fearless enough to allow you to read it; I blocked you from the publication link when I posted about it online. But I know you must’ve found it, one of our friends probably forwarded with concern, or you searched for my work, as I always hoped you would. Before we split, you supported my writing, regardless of how aggrieved it tended to be.

“Certainly you remember the guilt, the anger I instilled in our friendship, our stupid, wonderful friendship. I’m thankful for my life, but you carved a scar while trying to save me. You’ve ruined all future devotions to people, because I have to keep them at a distance to not get scorched again. Thanks a fucking lot. I will never feel happy in a new attachment because I have to keep my expectations wrangled in a cage, snarling to get out. Godamnnit. All I did during our broken time was hate you, miss you, forget about you, remember everything about you.”

And now I hate that I had to learn a lesson when I could’ve avoided it and have been a better person. You don’t deserve to live with my resentment. That chapter now feels like an epilogue and we’ve been shelved in a thrift store, left behind and discounted.

My temper is short / But I’m here, givin’ up my ground

I never give you a chance to breathe, and when we move out of town for college, I still won’t let up. Communication is so dramatic sometimes. I mail my side of a closure letter a month before moving to Nacogdoches for college. Before we ended I imagined us at the bottom of a sloped driveway, cinematically saying goodbye—we always knew we would move on, but not on these terms. It burned to not get the image after all. In the fall I receive yours, and there is so much relief. I look for your face everywhere still, despite knowing we’ve truly ended.

After a few months I had to train myself to stop looking at your social media, searching for clues that you were still thinking about me. Only once did I catch something—you sharpied my initials on your wrist for World Mental Health Day. That picture has since been deleted.

It’s only war if there’s a winner / It’s only hell if there’s a sinner

Christianity is something I can’t get with—but you are devoted. I go to church and endure sappy bullshit. You secretly want me to align with your faith but give up when it’s clear I can’t be saved. “If you just let Jesus in, you’d have a better life.” There is not enough energy in the world for me to fight back.

The summer between high school and college, you went on a mission trip to my home state. You posted the mailing address online and I could barely restrain from sending you letters, like the old days, to let you know I missed you and was happy to see you’re in my favorite place. But I knew you would put some religious spin back onto me, and I knew silence would be better than hearing your judgement.

And I’d do all the things we didn’t / ‘Cause I choose you / Yeah, I choose you

Imagine all the pictures we’d have today. The Starbucks selfies, the graduation snaps, the mini road trips, shrieking about first kisses and unrequited crushes, walking our dogs, crying when our dogs died.

I’m forgetting to notice the memories we’ve had and could’ve had in the corners of our haunts. When I land in Texas for the holidays I don’t expect you to show up at restaurants, though I did run into your mom once at Target—I couldn’t recall her name, but remembered all the afternoons she welcomed me over, shouted at us from downstairs for being too loud. As I order coffee I don’t think about your usual latte. You disappeared into the past collection of people whose faces are now strangers. If I heard your voice in the crowd, I would keep walking.

We put men on the moon / But I can’t figure out what is missing

As I make new friends in college, I fall further away. Instead of blaming you for friendship troubles, I force myself to take responsibility. Once I compared you to a friend who lived 800 miles away, and she called me out for being unfair. The manipulative poison hadn’t fully flooded out of my system, but I was trying. After that incident I finally found gratitude for those who could be around me, who remarkably enjoyed my presence.

And in every room / You’re right in front of me

At some point in my life I will burn your closure letter, but perhaps I’ll leave it to my afterlife to deal with. Only in September do I pull it out of a shoebox from the closet, buried beneath letters from other friends and personal documents, the things I can’t bear to misplace. Some years I forget to read it again. A great sign, I suppose, that time does heal.

We find pictures in stars / But they’re thousands of miles away

Our backs ached after we spent an hour sticking glow-in-the-dark stars on my ceiling, trying not to trip over each other on the twin-sized bed. None of it trailed into a cohesive constellation. You lied on the floor, stretched while I looked down at you. This is how we always sat.

Stargazer obsessed with pictures of bluebonnets in vintage film, some twin lost in the timeline, you used to connect your asterism with me. And once we started to feel miles away, when I started avoiding the lunch table to punish you, we’d grown so far apart we couldn’t see each other anymore. There was too much cosmic dust.

Sometimes I think we were a film that I made up in my mind.

And I’ll give you my all / But you take and you take and you take

This is when all my guilt swallows me whole, a sun pitcher plant opening to the sky, to release and return. I can’t imagine the pain I put you through, how triggered you were each time you crossed my laser beams of boundaries, how my suicidal texts abused your heart. And all I did was feel like I was giving, I was giving you a reason to live, to make me feel alive, when I only took so much, I took your life in a way, made you drop your friends, explain to your dad that I was bad again, no one but you could understand. I took so much from you.

I’m not the same as I was before / I’ll go through the walls and kick down doors

Now, after twelve years of getting over you, I imagine myself making an unnecessary counseling appointment in Texas, even though I am five states northwest. I know you’re a mental health counselor because of me. Or at least, partly. I’ve left too many scars as a guidebook for you to teach others how to heal.

I dream about your face when you read my name in your calendar. The surprise when I burst through the door, all silent and chaotic at once. How it must feel after a decade without hearing our cries beyond hauntings. In the dream I can’t get past the initial shock, I have no idea how we proceed from there. A cliffhanger with no ground to land on.

But I know I want to apologize a thousand suns for all the pain I put you through. I’m not a better person, but I’m better. The strings you cut from my palm haven’t been reattached to anyone else.

No, I’m not the same as I was before / And I wouldn’t hurt you anymore

When I got in my first relationship four years ago, you were not the first person I told like we’d always imagined—but I wished I did. I was so afraid to get in an argument and lose him like I lost you. I warned him, “If I ever become manipulative, let me know. I did that to someone and I can’t do that again.” Shame loves to feed on long-fermented fears.

We used to share a pint of ice cream on Friday nights, lied back on a parent’s driveway. The smell of neighboring sprinklers rusted our plastic spoons. At the time it all felt like a memory, and I was slowly falling out of sleep.

“You already know this, but you’ll be my maid of honor someday,” you said with half a bite of Neapolitan in your mouth. The chocolate side of the pint was carved in deeper.

“Of course.” I sat up and twisted to the left, scooping around the strawberries. “And if I ever find somebody, you’ll be the same.” My parents’ divorce spurned me from marriage and you saw the warpaths I had to wade through every day, being tossed into the middle all the time.

You got married five years later, and I don’t know who ended up being the maid of honor.

(I’m not the same as I was before; ooh) / It’s only war if there’s a winner

I’m engaged and I feel weird envisioning you in the audience. We promised to be at each other’s weddings and look where we’re at. But there are some parts of your life that followed mine.

You already love that I live in the Pacific Northwest, moved as soon as I graduated college; you visit Washington every year with your Texan husband—reason unknown, but it is suspiciously too coincidental when I’m the one who came from here and lamented daily how much I needed to be back permanently. Each time you post a photo album on Facebook I have to think you’re doing it for me, that you’re sharing what we could’ve done. That is awfully narcissistic and not. The more years that go by, the more removed I am from the pain. I can finally feel happy to share this place with you, even though we’re not together.

If you ever go to my hometown, I never know. I don’t think you want me to know that. But the smell of evergreens and Issaquah Creek, the fresh mulch teeming with wildflowers, the standoffish nature of strangers and drinking coffee in solitude, I hope you think about me. That despite all the ugliness I put you through, I still showed you something beautiful.

(I’ll go through the walls and kick down doors; ooh) / It’s only hell if there’s a sinner

The last time you acknowledged me was in 2017 about a grad school acceptance. We kept our intwining moments on Facebook to a minimum; I hid your name from the feed and blocked you on certain posts. I still wanted you to see and be proud of me. Taking a train through America, visiting my hometown in Washington to restore my sanity, publishing silly little essays and poems, finding that life did get better out of high school. Maturity, in some ways, that I wasn’t going to do the same horrible things to someone else.

I think I liked your wedding photos a year later, but nothing else past that. Our perpendicular lines extended too far to see the other line. I stopped dedicating songs to you, us, in such a naively platonic way. There has never been a chance to run into each other’s path. And if something major happens, we’ll keep looking the other way.

(No, I’m not the same as I was before; ooh) / And I’d do all the things we didn’t

Once, often, many, many, many times, I created scenarios in real life and you popped up perfectly to the script. On bad nights I imagined you driving three hours from Dallas to Nacogdoches, knocking on my dorm door and silently hugging me, the way you used to when we were kids, when I was terrified I wouldn’t still be alive in the morning. During holiday breaks I was antsy about serendipitously turning a corner past you in the mall, on my way into Forever 21, looking for a coat to swap with my friend. I heard this song and I thought, This would be an absolute bop ten years ago, and of fucking course it would play in a Forever 21. We are adults now and I can’t fit into a cheap factory’s version of plus-size clothing; I have to go to more size-inclusive stores like Old Navy (which isn’t any better environmentally, but engineeringly). I can barely remember you scoffing at a horrid floral top or rushing to avoid mean classmates in the party section. The mall was our safe spot, where we knew we could just be friends and my mental health wouldn’t be a third wheel. Something about being in a 1.5 million square foot space of options to change characters and clothes and sit in the silence of a movie theater and try to keep up with each other’s pace in the stores and arguing about remembering where we parked and laughing while swerving around traffic back home because we’re 16, we’re on the fringe of losing it, a story no one but us will tell.

I know now when I lost you, and it’s finally okay.

(And I wouldn’t hurt you anymore; ooh) ‘Cause I choose you / Yeah, I choose you / I do

Of all the people I can forget, at any point in my life, the wavy curls to after Sunday School hang outs, the long walks to the yogurt store that’s no longer there, I want to say I choose to forget you. Favorite color, ranting about your sister, playing video games in the dusky dark after a sleepover, thumb gently pressing A. You let me win at Mario Kart and tuck your blanket up. The dawning sky peeks through the shades, an orange glow sweeping our eyelids closed.

Our history is no longer ours, unequipped from fireworks that spring off when a memory arrives. Your name remains as a scar that won’t make me flinch.

E Townsend’s works have appeared in cream city review, Superstition Review, Prime Number Magazine, carte blanche, Orion, and others. Managing editor at Four Palaces Publishing, she’s also the managing nonfiction editor at Chaotic Merge Magazine and a reader for The Masters Review. A previous nominee for a Pushcart Prize, Best American Essays, and Best of the Net, she is currently tinkering with essays and poems in the Pacific Northwest.

Bryan Lurito: When reading your piece, “This is the Perfect Song for a Forever21 Store a Decade Ago,” what really drew me in was the exploration of teenage relationships and the transformation that comes with adulthood. What about this topic inspired you to recount and share your experiences?

E Townsend: I’ve written about teenage relationships a couple times and it’s a theme still strong in my life. The big sister essay of this was about my manipulation, using my mental health to control my best friend, just generally pathetic woe-is-me shit. I recently reread it and cringed. I didn’t realize how intense I was to her, and to anyone really, until I grew out of it. I didn’t intend to make this a redemption piece, but I needed some cathartic way to apologize to her, and to show myself that I have finally somewhat chilled out. The friendship ended well over ten years ago and her presence doesn’t weigh on me anymore. I’m so far removed from my teen years that it was like we never existed.

When the sister piece was workshopped years ago, some students made the comment that it’s rare to read about friendships that hurt worse than a romantic breakup. You never feel like you’ll get over it. But then you age, and you see where you went wrong, and the longing only feels like a dull ache. I had been trying to reconcile this for a while and finally had the vessel and emotional clarity to do so without making it a melodramatic diary entry.

BL: I found your sense of rhythm and voice to be particularly strong. How did you go about developing narrative flow when writing your piece?

ET: When writing I always need music, and it’s typically either the exact same song on repeat or the same playlist. The music then influences the narrative flow based on the pitches in the song, the tempo, the lyrical and vocal rhythm. And when I edit, it’s still based on the music that’s on. The song just feels like the perfect backtrack for broken teenage friendship, and I hope the reader will give it a listen while reading. Any song I write to/reference is meant to serve as an extra layer to the piece.

BL: I was particularly intrigued by your integration of a song into your piece. Was this song the inspiration for the piece, or something which built upon a pre-existing story idea? How did this affect your integration of the song into the narrative?

ET: I found the song through someone’s 15 second Instagram story, then listened to the whole thing on loop for three hours. I kept seeing a music video of our friendship, chasing each other through different sized clothing racks, and when it got to the really intense bridge, I imagined a heavy insane sequence of all our fights and pining and missing each other and it only makes sense to us but we’re no longer on the same wavelength so one of us could’ve wiped away the memories. It originally was going to be a love letter to Forever 21, exploring my other teen friendships while shopping in that store and mall, but the song took me elsewhere.

BL: I noticed you also have a history in poetry on top of nonfiction. How do you feel your experience in this second discipline has affected your voice as an essayist?

ET: My poetry professor often told me my poems were essayistic. When I started writing I wanted to be a dedicated poet, but then I discovered nonfiction and fell in love with telling the truth through that particular genre. It excites me to read a line with genuine surprise, a clever smirk at the writer for taking my breath away, so I try to do the same. I’m always looking at every sentence and thinking, if this was a standalone quote, how can I make it stand out? Poetry is full of quick quips and one-liners that transport you to another universe, so it’s fun to challenge myself to write as poetically as I can in a prose form.

BL: I enjoyed how you added several moments throughout your piece which are small on their own, but together aid in fleshing out the main ideas and narrative of the piece. How did you decide which moments to include within your piece, and what was the process of translating them to the page like? Was anything gained, changed, or lost in the process?

ET: When writing the glow in the dark stars scene, I didn’t mention that we also taped lyrics cut from magazine pages on the ceiling—Snow Patrol’s “Chasing Cars.” That was our song before we ended, focusing on the lines “If I lay here, would you lie with me and just forget the world.” The three lines before those, “I don’t know where / Confused about how as well / Just know that these things will never change for us at all,” kept us together for as long as we could believe in us. We had so many Friday nights lying on a driveway where everything that was going on with us disappeared. We had other things to talk about. I can’t really remember our friendship, which might seem sad, because at one point it was the only thing I would constantly think about. But we’ve grown up, moved on, and I don’t dedicate songs to her anymore (except this one).

BL: You have been published in quite a few magazines, and also serve as a nonfiction editor yourself. As someone who’s been on both sides of the process, what advice do you have for prospective authors looking to get their own works printed?

ET: Reading other people’s works has definitely influenced and inspired my own. I see the cleverness and the narrative mistakes, the one-liners that blow my mind and the sentences that need to be cut for concision. It has always been my dream to be an editor instead of a writer, but wearing both hats at once gives a really great perspective. Submit your work often, edit every single line, find friends willing to look at your pieces, and keep some sort of notebook (mine is the notes app on my phone) to store your ideas in. Your work will get published eventually—there is always a reader for every and any subject imagined.

An Interview with Lino Azevedo

Lino Azevedo was born to Portuguese immigrants near San Francisco. Like most small children, he enjoyed creating from the soul with simple tools like pencil and crayon. Being a painter herself, his mother saw the potential and let him try his hand with her oils and brushes. These formative years set him up for a life-long career in the arts. He currently is a Foundations Professor at Savannah College of Art and Design. Lino is an award-winning artist whose work has been exhibited internationally and published in multiple journals and magazines.

John John O’Connor: You mentioned that your parents are from Sāo Jorge then moved to Portugal, how big of an influence were they for you as an artist? Especially since your mother was an oil painter as you were growing up.

Lino Azevedo: My father was always doing something around the house and was very handy (and still is!) He even freelanced and built cabinets between jobs for a while. My brother and I would help him in the wood shop from time to time and he even built an attachment to the garage and a small bar-b-que house in the backyard. Besides carpentry, he knew the basics of laying down concrete and put in our entire driveway when we moved into the house that he still resides in. This “hands on” approach to learning really influenced me when I finally started to take drawing and painting seriously.

As a way to save money, but also as a creative outlet, my mother made her own clothes. She knew how to sew very well and had a room in the basement with an antique sewing machine. That is also the room that she would do her oil painting. My parents usually worked opposite shifts at their jobs when we were young. For a while, my Dad worked nights so my Mom would keep us busy after dinner by having us paint on cheap canvas boards. I remember being confused by how hard it was to control the medium but also intrigued by the creative possibilities.

Like many immigrants, both parents believed in hard work and making opportunities, not waiting for things to happen.

JO: You have received a bachelor’s degree from San Jose State University and a master’s degree from Winthrop University for art. Can you tell me how your studies progressed your development as an artist. Would you say university is a necessary step for an amateur artist?

LA: Ah, yes! The big question of whether artists should, or should not go to art school…

It really depends on the person. For me, the answer is “yes”. I enjoy the classroom setting and I learn better in that environment. I feel that the assignment deadlines and the friendly competition with classmates really helped with my development as a creative. As a matter of fact, I feel I’ve learned just as much, if not more, from classmates than the professor. In turn, I tell my own students that they are in the classroom to learn from each other as well as from me. My undergrad studies at SJSU really helped me acquire the technical skills I needed and then my graduate education at Winthrop was more about self-expression and experimentation.

JO: You have traveled all around – growing up in California, backpacking across Europe, moving to New York, Charlotte, etc. How much have your surroundings and the places you’ve lived influenced your art?

LA: The places I’ve been have very, very much effected my work.

Traveling through Europe really opened my eyes to the history of art. It’s one thing to see the work in an art history book, but a totally different experience to see Michaelangelo’s Sistine Chapel by looking up at it and realizing it was finished centuries before the United States was even a thing.

Of course, moving to NYC was a tradition for many creatives. Actually, it was more of a necessity. The city was really the art capital of the world for decades. It had the best galleries and museums in the world as well as all the major publishing companies. Another aspect of the city is how difficult it is just to survive there. You know what they say, “if you can make it in New York…”

I think that living for lengthy periods of time in both “blue states” and “red states” has really helped me acquire a more open minded perception of people’s views. Understanding is knowledge, and knowledge is power!

JO: A lot of your art involves pieces having to do with social commentary. As for your messages in these works, are they messages that you think about for a while as you build up an idea? Or are they something you see and feel a need to respond?

LA: I would say both.

I’m very affected psychologically by many of the injustices and atrocities going on in the world. Sitting down and sketching out ideas is almost automatic after reading about or viewing these stories on the news. These events definitely have an immediate impact on much of my work.

Often, however, there will be something that develops slowly and may take months to actually evolve into anything finished. As a matter of fact, it may even change meaning or have a very “vague” meaning. Often, the “feeling” of the image is more what I’m after than an obvious statement. This is my favorite way to start a conversation.

JO: One of the largest and most complete works you have done was your series on lobotomies. How did the idea for this come to fruition and what was the original message you were trying to send? Also what do you think the importance is of using unsettling imagery in art?

LA: In this case, lobotomy, or lobotomized, is about society either being manipulated by the certain entities or choosing to be ignorant of these possibilities.

Actually, the idea for the Lobotomy series was only a concept for one painting. I had an idea for a half dead old guy with a stitched up circle on his head from the removal of part of his brain. I loved how it started to come out while working on it and then sketched out other “foreheads”. Some of these symbols included known logos from big companies. I kept going with these different portraits, eventually creating a series.

Using “unsettling imagery” is sometimes necessary. Like the John Doe character from the Seven movie stated, “It’s not enough to just tap people on the shoulder anymore…you have to hit them over the head with a shovel.”

JO: You now teach art and work as a Foundations Professor at Savannah College of Art and Design in Savannah, Georgia. Can you tell me how being a teacher and working with students has changed your approach to art? Or if it has changed your style at all?

LA: Teaching Foundations classes, like the very first drawing classes that first year freshmen take, is something I take seriously. Many of the professors I had in college were taught by the Abstract Expressionists of the generation before. These professors lacked the skills or interest to teach the fundamentals of drawing, design, color theory, etc. I remember one guy would even sit in the corner and try to teach himself guitar while we worked on some unfocused assignment. Don’t get me wrong, self expression and “art for arts sake” is very important, but I want my students to be noticeably better at the basics of drawing when they leave my class versus when they started.

One of the best things about teaching a generation younger than me is the link to artists and styles that are currently in fashion instead of always going back to my old favorites. I feel like these students have opened doors for me and I have all these new toys to play with as far as influence and directions.

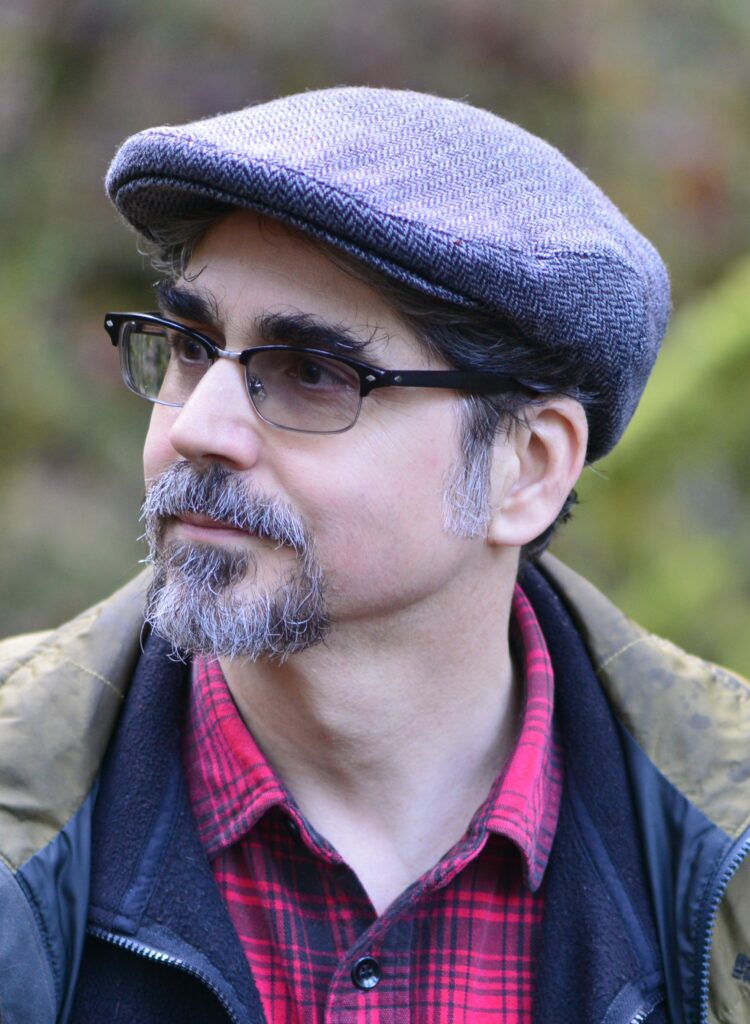

An Interview with Jeff Fearnside

Jeff Fearnside is the author of two full-length books and two chapbooks. His poems have appeared in numerous literary journals and anthologies, including The Paris Review, Los Angeles Review, Valparaiso Poetry Review, and Forest Under Story: Creative Inquiry in an Old-Growth Forest (University of Washington Press). Honors for his work include writing residencies at the Bernheim Arboretum and Research Forest and the H. J. Andrews Experimental Forest, the Peace Corps Writers Poetry Award, and an Oregon Arts Commission Individual Artist Fellowship. He has taught writing and literature in Kazakhstan and at various institutions in the U.S., currently Oregon State University. Read his most recent book.

Ashley Goodwin: What inspired you to write “The Way of the Seeded Earth?”

Jeff Fearnside: Oregon’s Coast Range mountains are just minutes from my home, and my wife and I have spent countless days exploring them. One of the beautiful and ubiquitous creatures living in this range is the salamander, in particular, the rough-skinned newt. I’ve had a chance to closely observe them on numerous occasions in all seasons, and the poem came out of those observations. Its title comes from the title of a book by Joseph Campbell, and while the poem isn’t directly related to that book in any way, the title suggests what I wanted to convey, what salamanders so strongly embody: This is how the world seeds itself. This is how life moves through life.

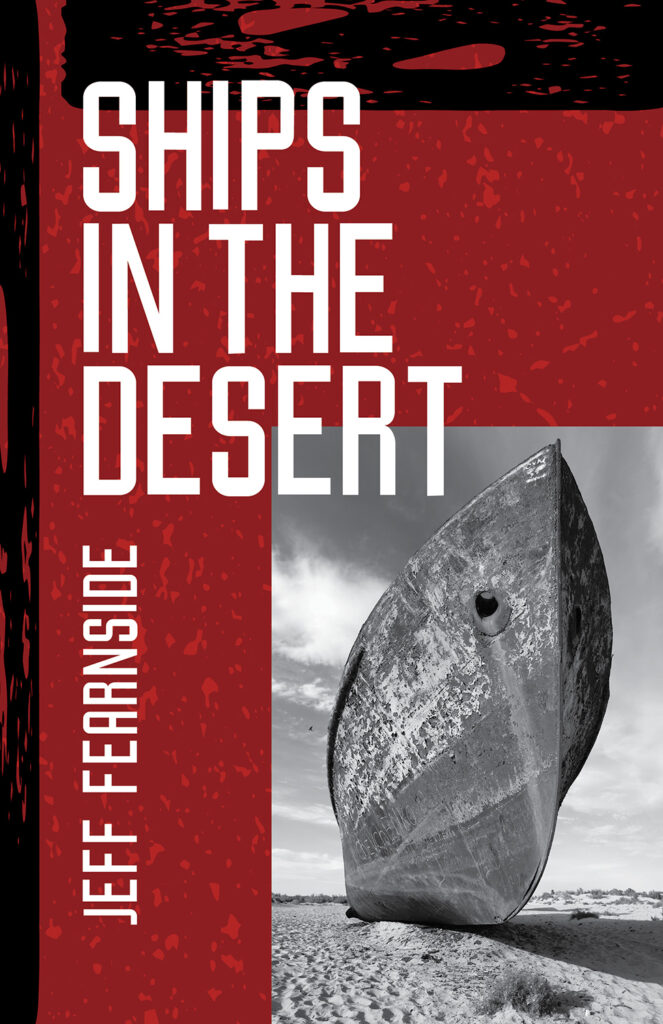

AG: Your most recent book, Ships in the Desert, recently won the Foreword Indies book of the year award and the Eric Hoffer Book Award. Could you describe the book for people who are just hearing about it?

JF: I’m happy to say it also just won an Independent Author Network Book of the Year Award! It’s a collection of linked essays about my four years of living in Kazakhstan, so it’s very much a personal story. It’s also about the environmental challenges we face today, particularly in regards to water, as explored through a trip to the dying Aral Sea in Central Asia. Finally, it’s about culture, the differences between East and West, and how we might better understand each other. So anyone with an interest in the environment or other parts of the world should find something of value in it. It was definitely a passion project for me.

AG: What is your process for composing?

JF: It depends entirely on the piece. I believe process is dictated by the particular qualities of each piece, and that my job as a writer is to discover what those particulars are. So writing for me is a process of exploration. Sometimes, right from the beginning, I’ll have a very clear idea of what the piece is or seems to be, while sometimes I’ll begin with nothing but a single phrase or idea in mind. It doesn’t matter. Once I start writing, I let the words lead me. I work very intuitively while drafting. I bring my knowledge of craft into the process during editing, though the goal is still the same: discover what the piece wants to be and help it become its best.

AG: What made you want to become a writer?

JF: Reading. I loved reading as a kid, and I wanted to do what the authors I loved were doing: to make the kind of magic I felt when I read their books. It really was that simple. Of course, I grew older, discovered all kinds of different writing from all over the world, critiqued it, came to understand the technical aspects of it. All of that was good. But I still feel my writing is best when I don’t overthink the technical aspects of it and simply approach my work with a child’s sense of wonder. That’s what as an adult keeps me writing.

AG: What advice would you give to young writers?

JF: Read, read, read, and write, write, write. Nurture your imagination. Find inspiration everywhere, not just in your favorite books but also in the ones you think you don’t like. Devour it all. And don’t forget to live. Allow yourself to fully feel your experiences, both positive and unpleasant, as well as everything in-between. Come to know yourself through your life and writing. Don’t be afraid to make mistakes. Be human.

AG: What are your favorite books to read?

JF: I love just about everything, from realism to magical realism, from the dead serious to the surrealist, the satirical, the humorous, even so-called genre writing like the mysteries and science fiction that first inspired me when I was a boy. I love fiction, poetry, nonfiction, drama. I’m one of those strange people who reads Shakespeare for pleasure! I’m an omnivorous bibliophile. A bibliovore. But like most people nowadays, I’m busy, and I’m a slow, careful reader—the more I like a book, the slower I read. So simply as a practical matter, I most often gravitate to story and poem collections, books I can savor in parts even if I don’t have a lot of time to read. I really don’t understand why short stories are supposedly such a hard sell. Given how crazy busy everyone is today, I would think that short stories would be more popular than ever! And what can one say about poetry? Good poetry is like water or blood. It’s necessary to life.

More info: http://www.jeff-fearnside.com/

Jebel Irhoud

This is where we came from.

This is where we lived,

in a Moroccan cave

315,000 years

before Morocco,

before language and time

as we know it.

We had come far already

from the east,

spreading across a continent

with stone tools,

curiosity and cunning.

The songs in those bones

still play in ours,

whistling through marrow.

The dances they danced

still coil in our muscles,

sprung free

whenever we move

from our centers.

Pick up a piece of flint.

Do you remember

the scraping of tendons,

the scuff of hide?

Something calls you

to test the keen edges,

turn the stone over and over

in your palm.

Build a wood fire.

Contemplate the stars.

Paint with your fingers,

pull weeds,

feel the rasp of grass seed

against flesh.

Seek shelter from a storm

in any natural place.

Turn your face upward,

lick the drops rolling

off your lips.

It’s the same water

of the first rains

and rivers and lakes.

That prick of blood

where you got snagged in the wood

tangs of the same salt

of the first oceans.

The Way of the Seeded Earth

We humans think we have it rough.

Try mating underwater

with two—or four or six—

would-be suitors cutting in

on your amplexus.

But for those

ultra-sticky nuptial pads,

you’d be pulled apart.

It can take hours. The mass

of bodies rolls and clutches

in a shallow pool, tails like

streamers or spiral arms

of galaxies in the cosmic amnion,

like a ball of baby snakes.

On land they move

separately, somnolently,

each step a lesson

in what it means to stake a claim

to one’s terrestrial heritage.

Yet two salamanders

left unharried in wedded embrace

swim, turn and dive to bottom

as a single body,

a single current

in all that surrounds them.

Speaking with the Dead

The dead don’t speak

only to the dead,

though they prefer it.

To walk in nature

is to initiate a séance.

Spirits knock on wood,

rattle vines,

raise the forest floor

and speak in whispers

along creekbeds

and in drainages

that channel warm drafts up

and cold drafts down.

The coldest lie stagnant

in hollows.

You will hear

most clearly there.

To speak with the dead,

go to the low places.

Let them approach

and then ask your questions.

Only know this: the answers

may come from anywhere.

Elk Hotel

We didn’t see them, but we knew they were

somewhere near, hiding from the day and us

in the darkest part of the woods. Their trails

run through this place: to shelter, to water.

Hoof prints lie stamped in mud, while black droppings

like breadcrumbs occasionally offer

paths our muskier selves long to follow.

We’ve seen them before, gathering to feed

at dusk at the edge of a nearby field

redolent with the succulent flowers

they savor while bathing in the dying

light, the cool air, the comfort of safety.

In our refuge from coronavirus

we often come here to walk out all that

we do not wish to talk or think about.

We’ve forgotten what it means to be free.

Each time, we’re amazed that the woods doesn’t

have to wear a mask, that the sky can breathe

so heavily upon us without guilt.

We know the herd has visited because

just behind the thick hedge of blackberries

in the lowest point of the depression

stands the grand Elk Hotel. The matted grass

details reservations for two dozen.

It’s all about location—privacy

assured, amenities accessible

within the stretch of a sinewed foreleg.

I can imagine them in swimming trunks,

lolling at the edge of the slough, talking

of the news of the day, shaking their large

antlered heads while sipping wild blackberry

cocktails and wondering just what is so

especial about those animals with

their shrill protestations and smoking guns.

Belonging

On a log in the creek

a hollowed-out knot

where a limb once reached

to the sky. In the knot

pebbles, pale and smooth,

like a clutch of hummingbird eggs

on a bed of creek sand.

Tiny sprouts of green

grow between the pebbles.

Cottonwood seeds like down feathers

rest comfortably, protected

in the log-walled hollow,

the entire space the size

of a large chicken’s egg,

or the polished jade oval

we saw in the gem shop

while searching for garden rocks.

Your hand was a gemstone

or an egg

in my hand

even after all these years.

An Interview with Donna Vorreyer

Donna Vorreyer is the author of three full-length poetry collections: To Everything There Is (2020), Every Love Story is an Apocalypse Story (2016) and A House of Many Windows (2013), all from Sundress Publications. Recent work has appeared or is forthcoming in Ploughshares, Colorado Review, Harpur Palate, Baltimore Review, and Booth. Her visual art has been featured in North American Review, Waxwing, About Place, Pithead Chapel, and other journals. Donna currently lives and creates in the western suburbs of Chicago and runs the monthly online reading series A Hundred Pitchers of Honey.

Charlise Bar-Shai: What made you want to become a visual artist?

Donna Vorreyer: I have always loved to view visual art, and I was lucky enough to grow up with the Art Institute of Chicago just a short el ride away. I also used to love making visual art when I was young, and even won keys in some Scholastic Art competitions in junior high. But I moved away from it as I grew more interested in writing, and since I had limited time for creative pursuits as a full-time middle school teacher, the writing took precedence. I retired during the pandemic lockdown, and having so much time at home allowed me to start tinkering with some attempts at visual art: small daily sketches of things I had around me at home, some black and white grid portraits based on old photographs, some collage work with found material. The joy I got from that sort of creative work was less stressful and different from writing. I decided to take a class with poet Ciona Rouse and her sister, artist Lanecia Rouse Tinsley, and their encouragement to use what I knew from the writing process to explore the visual set me on a path to start creating more visual art. Over the past three years, I have used their encouragement (as well as online videos and tutorials) to try to grow as a visual artist, focusing mostly on abstract work. I do it mostly for the enjoyment of it, to see what I can learn, how I can grow, what themes emerge as I learn to experiment with shape, color, and texture.

CB: Have your written works inspired your visual pieces? Is there an overlap in your creative process?

DV: That’s an interesting question and the answer is no, not really. So far, it has been helpful for me to keep those two processes separate. I have been writing my whole life, and I have had some “success” as a writer, in terms of publication, so I feel a certain type of pressure when I’m writing, a pressure to make it “good,” to live up to what I’ve done in the past. I have no such ego about art. I can more easily mess up and laugh about it than I can with the written word. In that respect, making visual art is less stressful for me than writing, and I’d like to keep it that way.

Working on a poem has a completely different feel than working on a painting, but what writing and painting have in common is that they both start messy – just getting things down, not necessarily focused and certainly not precise. It is in the next steps that they diverge. When I write, I love to revise, to focus on the diction, the sound, the line breaks and form, sometimes over months, before deciding that a poem is done. Each of these moves is deliberate as I make my way toward a final piece that is doing what I want it to do. In making visual art, I have a tendency to experiment more, to add and remove elements until I have a pleasing arrangement, sometimes completely foregoing an original plan or idea to follow something that emerges in the making.

CB: Did your time as an educator influence your artistic process? Did your students inspire you?

DV: My students always inspired me when I was teaching, not only with their own talents but with their joy and openness to the world, their ability to take risks and try things that were new to them. In that way, I think that they have influenced my process in the sense that I have had to follow my own advice. I used to tell my students that no one could ever ask them for any more than their best, and that doing your best is what matters, even if it doesn’t have the result you want or expect. When I make a piece of visual art, I keep that mantra in my head, as things often don’t turn out how I want or expect them to, but I’ve found a way to embrace that and move forward from those “failures” and see what I can learn from the experience.

CB: Have you arranged a solo exhibition for your work? Do you have a plan for one?

DV: I still have a hard time calling myself an artist, and I also have absolutely no knowledge of navigating the world of art in that way. (I have noticed that it is very expensive to enter shows, etc., which makes me nervous.) But my local library will be exhibiting a collection of my work in the new year, and that is exciting to me. So far, I have stayed within the world of literary journals, which is familiar, in terms of sending my art into the world to see what others may enjoy. Who knows what the future might hold?

CB: What has been the biggest challenge you’ve faced as an artist so far?

DV: The biggest challenge has been to let go of my inner critic. My good friend, writer and artist Kristin LaTour, has been so helpful to me in that respect—if it’s no good, it’s just paper. Throw it away. If it’s on canvas, paint over it. Just have fun. And I’ve also created a group of writer friends who also make visual art —we live all over the country, so we share in a group online where we are sending work, what we are making, how we are feeling about it. It’s helped me keep moving forward, to view myself as an artist, and to recognize that I don’t have to be a good representational illustrator to create something beautiful.

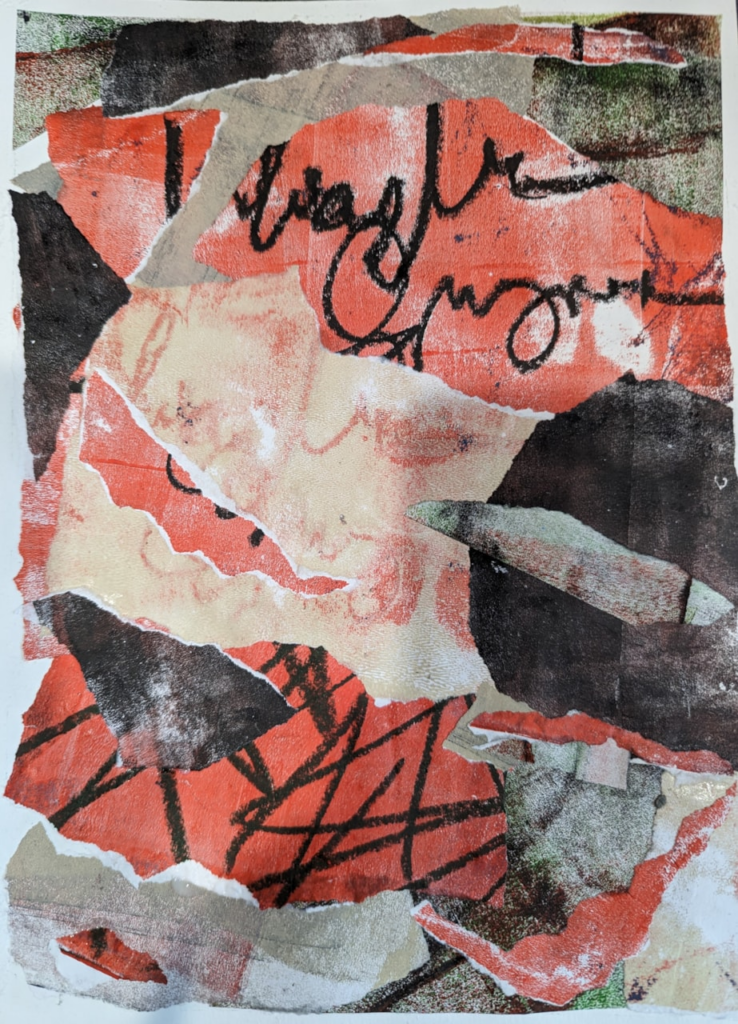

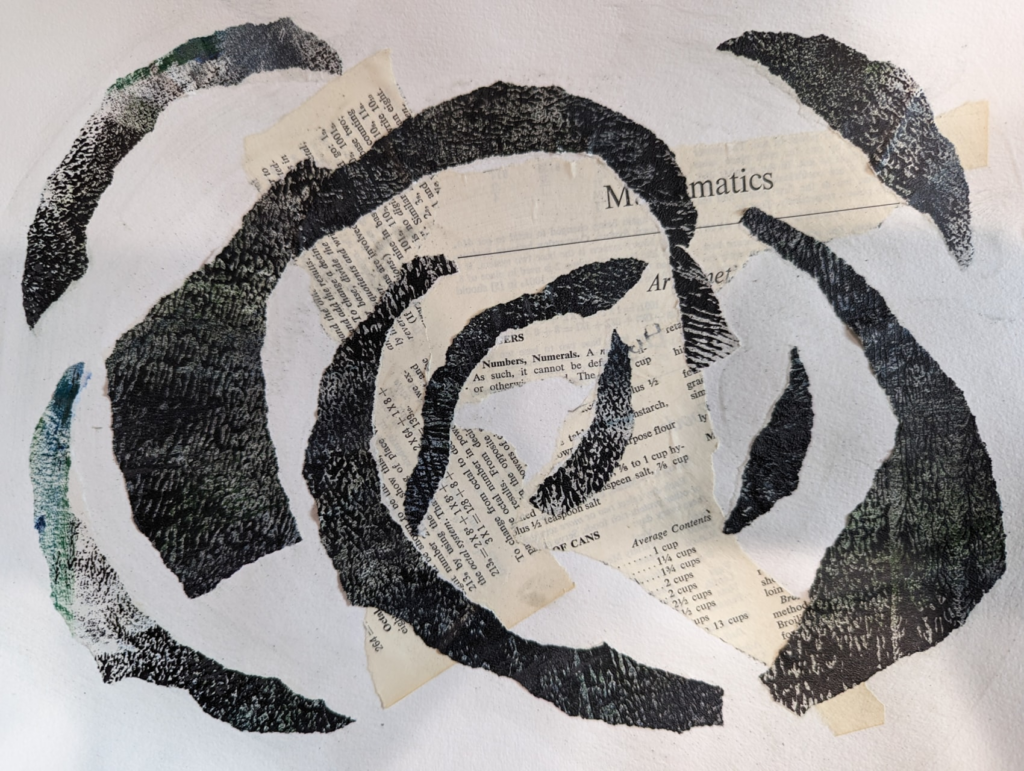

CB: I want to discuss your piece “Order and Chaos.” I love the way you seamlessly blended painting and collage. Can you describe your process when creating it?

DV: “Order and Chaos” began with collaging pieces of an old dictionary page regarding Mathematics. I placed them haphazardly onto the paper, almost in defiance of the rules and order that Math requires.

The other layer began with creating painted papers in dark shades (mostly black) with hints of greens and blues. Once the papers were painted, using a brayer to leave the grainy texture, I ripped them into curved shapes before placing them in a cyclical pattern that was more orderly than the text pieces. I like that the piece can work in multiple directions and places the text almost in the “eye” of the circles.

I often paint and rip papers to give the appearance of brush strokes in collage rather than using clean edges. I find it pleasing and more organic. I’m particularly pleased that this piece now has the perfect home with a dear friend who was a Mathematics teacher for years.

An Interview with Meg Tuite

It’s Never Lonely in a Unitard

Jules spent adolescence entering garments with flexible flourish. Leotard the III tightened the skin of his royal last name. Rooms stepped around him, encompassed his acrobatic torso. If ever a toe haltered the stiletto point, it was his. His performances scattered worldwide, lisped from pursed lips to the downward flare of nostrils from one landowner to the next. He yearned for these collusions with applause. It was enough swell of ego to gust the wind through his unrepentant bowels to last him a lifetime of meteor-showered luminosity of relief.

When the Spring of Jule’s youth undid him, something outside the margins of reality strangely knotted itself into frenzied updrafts when he colluded with Miss Happ–an operatic soprano from Dodge City, Kansas: the windiest city in the US. She diffused air circulation into microbursts of high and low pressurized notes and somehow solidified sound into weather.

Frictional force flanked Miss Happ’s vibrato into a paroxysm of whitecaps and clouds. A chronic surf from the sky regurgitated rain and hail through Miss Happ’s polyphonic chords and Jule’s ‘double cabriole derriere’. Not even the circus traveling ahead of them with Siamese twins from Yakamo, and a 90-year-old looking infant could capture a quarter of the fanaticism of crowds who gathered for Jules and Miss Happ. Somehow through the margins of their 20 flat, skeletal cranio-facial muscles, within and without, the duo manipulated resonances of vocal tracts and leapt through thick, stilted air to arouse downpours to disgrace droughts, when landowners spent most summers weeping over parched crops.

When Jules and Miss Happ parted ways, he took root with climate and radiance. Town after city after town drowned their desire in his exquisite array of unitards. His rainbow-hued onesies diffused the torment of tangled couples unsettled by sexless agitation, over-cleansed cottages, and reassessed orientation. The audiences spun in circles. They rallied their particular gods. They whooped with Jules.

Every town dealt its own bleating fear, and through the flow of water found ecstasy.

And somehow, the wreckage of a swollen river bared itself and raged through every lack.

Meg Tuite’s latest collection is Three By Tuite. She is author of six story collections and five chapbooks. She won the Twin Antlers Poetry award for her poetry collection, Bare Bulbs Swinging and is included in Best of Small Press 2021 and Wigleaf’s Top 50 stories for 2022, 2023. She teaches writing retreats and online classes hosted by Bending Genres. She is also the fiction editor of Bending Genres and associate editor at Narrative Magazine. http://megtuite.com

An Interview with Lauren Tess

The Machine

Past Lucky Diamond, Montana Lil’s, casinos

roofed in Lincoln Log green. Past Lithia

Ford and Montana Motor Mall, cars shining

back the blue sky knife-edged white.

Past Albertson’s and Ace, I turn off at last:

The Bitterroot—I say it as if I can claim it—seems

to languish as it rests at ebb, biding time. I mine

rocks like gold from the only uniced spot, the eaten

away bank. My toddler throws them in the river,

shallows it. More:

I claw all I can from amid pine roots.

Shamelessly, to please her, feed her needs

and have her touch the earth I take it, eat away.

What’s that if it’s not what water does, unblamed?

Our going-to takes away.

Our staying takes it too:

Ice clutches bed rocks all its rest then with this

brutal blue takes off with them, drops them

downstream when it reevolves to water.

On the road home we stop for bowls. Disposables

pass through my hands to a large black receptacle.

Does everything return to earth? To us? I do not

like the food but eat it anyway because she does.

I’d raze a forest, dam a watershed. I’d cut out the heart

of the country and give it to her. Full now, I drive on.

Back past the dealerships with their lots of cars

just like ours, glinting like pebbles in the sun.

Past the casinos, warm and dim and carpeted,

little wombs where you drop a coin in the machine

and hope somewhere down the road it gives it back.

Lauren Tess’s poetry appears in or is forthcoming from a number of journals including Poetry Northwest, Nimrod, Salamander, Meridian, and Cimarron Review. She received a 2023 Academy of American Poets College Prize as an MFA candidate at the University of Montana, and a 2021 Open Mouth Poetry Residency in Fayetteville, Arkansas. Lauren currently lives with her family in Missoula.

Ashley Goodwin: I’d like to talk about your poem “The Machine.” I was moved by the bond between a mother and her child. Could you describe how you came to write this poem?

Lauren Tess: Thanks so much! It’s lovely to hear that you were moved by the relationship in “The Machine.” When I sat down to write, I wasn’t thinking about circularity, an idea I only came to as I was composing the last stanza. Some things on my mind at the time were the outing itself, which was essentially as it’s described in the poem, and some guilt at pulling rocks out from between the exposed roots of trees just barely clinging to the riverbank. I felt I was accelerating their demise.

To get to Maclay Flat Nature Trail on the Bitterroot River here in Missoula, where we go in this poem, we have to drive down Brooks Street, which is overrun with big-box stores and car dealerships. I’m always trying to love and find value in these eyesores, these artifacts of our greed. Then there’s a jarring contrast between this commercial corridor and where it leads: these trails at the base of the Bitterroot Range. I wanted to make a world in the poem where the two locales aren’t mutually exclusive, and one isn’t the doom of the other. I’m not sure I succeeded, but after the first draft, I saw that some of the stanzas began and ended with the same word, and thus, I discovered a cyclicality in the poem that I hope for in life.

I’m choosing to have the long view, that the desires that brought about Brooks Street are the same desires that can save the world. That the love I have for my daughter, even though it leads me in this poem to selfishly pollute, waste, and claw away at the riverbank, is at heart completely selfless and full of hope, and that we all have this selflessness and hope in us, and it can be found anywhere.

AG: What is your process for composing?

LT: When I sit down to write, I usually take time (lately, an hour or more) to quiet my brain and arrive at a kernel from which to begin a poem. The kernel is often a mundane moment or outing. Then I write, by hand, in an unlined notebook. The writing itself takes less time. After that, I type it up, adjusting line breaks where needed to what feels like the right line length. Sometimes during the transfer I will change a couple of words.

AG: On your website it shows you have two forthcoming poems called, “Turnout, Highway 200” and “Hoverfly.” What can you share about these?

LT: I like to think these both also touch on my effort to reconcile being an animal that has happened to evolve some different traits from other species, and also being beholden to the built world in almost all aspects of my daily life. “Hoverfly” is about taking a walk as I was preparing to move apartments and observing the insect lift off from a flowerhead. Also in there is Beryl Markham, the first person to fly solo and non-stop west across the Atlantic, and her gliding over the ocean toward Nova Scotia after her plane’s engine died, suspended in uncertainty. (She crash-landed and was okay.)

“Turnout, Highway 200” is about a few minutes spent with my partner and our daughter on one of those scenic pullouts here in Western Montana. We had meant to go for a proper hike in an archetypal wilderness, but this ended up being our outing. We were by the side of the two-lane highway, and on the other side of us was the Blackfoot River and huge mountain peaks. Since I always feel like an interloper, the in-between space of this turnout felt like home for me, for the few minutes we were there.

AG: What is the most important piece of advice you have received as a writer?

LT: That’s a tough question! Sometimes I feel like I can make anything into writing advice, for better or worse. My partner Brendan, who’s a writer, has often urged me not to revise too much, and this has been really useful advice. I know a lot of people find extensive revision to be an essential part of writing, but that’s not the case for me. Usually, I find it best for myself and my writing to abandon a poem that isn’t good rather than try to make it good. I write poetry because it’s fun and exciting and teaches me things about myself. In dedication to this fun, excitement, and discovery, I choose to write a new poem rather than try to revise a mediocre old one.

AG: What are your current poetic influences?

LT: Lately, I’ve been inspired by Donna Stonecipher and Ed Roberson. They have mastered certain things I’m working on in my writing. As I read their poems, the words travel along my tendons; I feel their writing in my muscles, and I become more dimensional and feel my physical being as part of the physical world, and this is a joy. In The Cosmopolitan, Stonecipher shifts scales and locations so deftly, and writes about cities as if they were intimacy deployed or deferred; in her poems, the built world is as tangibly organic as a heliotrope. And Roberson’s syntax is always like oxygen; I think maybe my breathing actually changes when I read it, as his writing makes me feel euphoric. His poem “Prairie with Road” from MPH is one of my favorites.

AG: What does your writing space look like?

LT: My writing space right now is a slightly uncomfortable armchair in one room of our apartment. We call the room the office. The chair is beside a window with a view into a maple tree’s canopy and our apartment parking lot. I do not like to write poems at a desk or table, and I need to have a view to outside. I always write during the day; I don’t think I’ve ever written a good poem at night.

An Interview with Sofia Wolfson

The Book of Numbers

Our heads bobbed up and down like buoys. I flailed my limbs how the swim instructor taught me, desperate to keep myself upright. I’d never swum in the ocean before, finding the texture and flow of the waves unmanageable. All I’d known was the stillness of the chlorine pool at the tennis club, where I’d spent long hours floating in the shallow end while the adults drank.

But this wasn’t Palm Springs. This was Sicily.

For the first time in my life, I was undergoing jet lag, never hungry at mealtimes. I slept in two-to-three-hour intervals on top of the covers, sweating out of every pore, the ceiling fan more decorative than functional. Aunts and uncles and grandparents and cousins had made the trip for my great aunt’s bat mitzvah. When she retired from the Red Cross in the 80s, she followed a lover to Sicily who soon abandoned her for someone younger. But it wasn’t in her character to return home defeated, so she stayed. After spending her adult life as a devout atheist, she claimed that God showed himself to her in the ocean one day, not unlike the parting of the sea. She reconnected with her Jewish identity, at first practicing privately. Once she could confidently sing the prayers in both Hebrew and Italian, she joined a local congregation, whose recent formation symbolized the end of Jewish persecution in the area. Soon, between Shabbat and holidays and volunteer projects, her whole schedule was defined by the temple. Her bat mitzvah would be the culmination of her new identity, a permanent marker of her faith. At 75, she was the oldest person in her community to undergo this tradition.

On our third day in Sicily, I felt a stinging underneath my belly button, then a warmth in my groin. I rushed to the café bathroom to find a splotch of maroon in my Gap underwear. I took about 20 squares of toilet paper and folded them into a sturdy rectangle. Thankfully, the pseudo-diaper couldn’t be detected under my flowy skirt, the silhouette hidden under layers of paisley cotton. It wasn’t until later that night when my mom spotted the blood in the trash can that she finally knew what had occurred and offered to teach me how to insert a tampon. I screamed as it went in and she hushed me, fearful we’d wake my grandparents in the next room, who we were sharing our suite with. She ran her fingers through my hair and assured me that I’d be alright, that she didn’t start using tampons until she was in high school. I wasn’t sure if she was telling the truth or just trying to get me to feel better. Pads were going to have to do for now, even in my bathing suit.

The trip was the most time I’d ever spent with my mom’s side of the family. Most of her relatives lived in Palm Springs, where she grew up. Up until then, we’d only seen them for brief visits around the holidays. After my mom graduated from UC Berkeley, where she met my dad, they settled in San Francisco, got married and had me. She was often called the black sheep of her family, an animator amongst lawyers and doctors. Our relatives never made an effort to understand her, which alienated us from them. The car rides to Palm Springs were often plagued with a sense of fear of what my uncle or grandma might say to antagonize us, although they always hid their insults behind the guise of play.