When talking about The Agency Theater Collective it would be easy to rattle off a version of our company charter. In fact that’s not terribly dissimilar from what I nearly did when I sat down to write this—sorry, I’ll admit it, I can be a lazy writer sometimes. So I was sitting at my computer trying to figure out the best way to hide my laziness when an idea hit me: I could just tell you a story. Some creative nonfiction on how I came to be a part of the company instead of the (most likely) unreadable alternative.

Where to start, where to start…okay, I suppose that if I’m going to give you a full picture—a real sense of the whole—I need to start with when I was a young man living in London. It was spring, if I’m remembering correctly, and I had just turned eleven. My father and I were walking the cobblestone streets of Chelsea when a man ran my father down with his carriage. From that day forward I swore veng…Not buying it? Was it my inability to set it in the correct century? Right, I guess that I can be overly imaginative from time to time. I hope you’ll forgive me; it’s just that the real origin story, well, it doesn’t jump off the page like a murdered parental figure would have. But I guess I did say nonfiction so I guess that’s what I owe you. So here it is; here’s the real origin of my joining The Agency: it began in a meeting.

I warned you it wasn’t going to jump off the page, didn’t I?

T hat meeting really did change the trajectory of my life though and in such a dramatic way that I felt like giving it the sort of fanfare that it deserved (hence the ill-conceived story earlier). The meeting in question was between Superstition Review’s fiction editors, Mai-Quyen Nguyen and myself, and the magazine’s founding editor, Patricia Colleen Murphy. Without getting overly in-depth—trust me, it was tough (I had to erase a whole paragraph)—we talked about the fiction submissions and, ultimately, which we wanted to see part of the 11th issue of s[r]. I hate meetings as much as the next guy, but these didn’t feel like meetings, or work, at all and were often the highlight of the week. There’s seed number one.

hat meeting really did change the trajectory of my life though and in such a dramatic way that I felt like giving it the sort of fanfare that it deserved (hence the ill-conceived story earlier). The meeting in question was between Superstition Review’s fiction editors, Mai-Quyen Nguyen and myself, and the magazine’s founding editor, Patricia Colleen Murphy. Without getting overly in-depth—trust me, it was tough (I had to erase a whole paragraph)—we talked about the fiction submissions and, ultimately, which we wanted to see part of the 11th issue of s[r]. I hate meetings as much as the next guy, but these didn’t feel like meetings, or work, at all and were often the highlight of the week. There’s seed number one.

Not much further down the time stream my playwriting professor, Guillermo Reyes, asked for help on a play he was directing called American Victory. I volunteered to act as media technician and thus was planted seed number two. I stayed up until midnight trying to get my cues running smoothly alongside the actors, director, and stage management. All those artists working together on a single artistic vision until the wee hours of the morning? I was hooked. From that first early a.m. arrival home I knew that sort of collaboration and dedication needed to be a part of my future.

So the seeds planted by my professors and courses took root and grew. Three months after graduation everything I owned was packed into a wooden crate and on its way to Chicago.

Okay, so I’ve gotten you as far as Chicago and this is where it picks up, I promise. I moved to Chicago with absolutely zero prospects; only a desire to join the theatre community there. I spent my first serval weeks combing sites looking for a job in the theater arena and found a posting for the Chicago Fringe Festival. Fringe takes place over the course of two weeks each year and features hour long theatrical performances that are uncurated (applicants are selected lottery style). I could tell you that this means a wide range of shows spanning the gambit of performance from a rap musical (Lil’ Women) to a one man show about being black in America (Superman, Black Man, Me! A Stage Essay) to a live radio drama (Our Fair City). I could tell you that (and I did), but what the Fringe truly was, what the Fringe is, is a gathering of artists, volunteers, and patrons whose only goal was to create/witness this wide variety of (often) less than conventional theatre. It was also my first big step into the theatre community of Chicago.

Okay, so I’ve gotten you as far as Chicago and this is where it picks up, I promise. I moved to Chicago with absolutely zero prospects; only a desire to join the theatre community there. I spent my first serval weeks combing sites looking for a job in the theater arena and found a posting for the Chicago Fringe Festival. Fringe takes place over the course of two weeks each year and features hour long theatrical performances that are uncurated (applicants are selected lottery style). I could tell you that this means a wide range of shows spanning the gambit of performance from a rap musical (Lil’ Women) to a one man show about being black in America (Superman, Black Man, Me! A Stage Essay) to a live radio drama (Our Fair City). I could tell you that (and I did), but what the Fringe truly was, what the Fringe is, is a gathering of artists, volunteers, and patrons whose only goal was to create/witness this wide variety of (often) less than conventional theatre. It was also my first big step into the theatre community of Chicago.

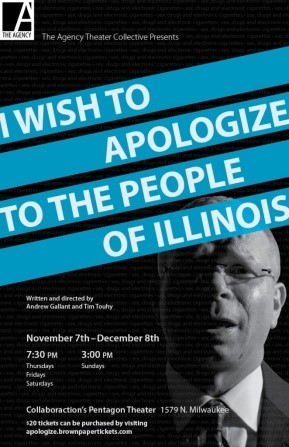

While working at Fringe I met Cecilia, a company member with The Agency, who offered me a position as assistant stage manager for the company’s upcoming play about political corruption in Chicago, I Wish to Apologize to the People of Illinois. I spent the next several months working in a field that I was fairly green to and trying to absorb as much as I could. It was also the slow season for my freelance work so I existed almost entirely off of giant bags of licorice brought in by the show’s stage manager. I was hungry, cold (the transition from the Southwest to the Great Lakes region is not the easiest), and worried that I wouldn’t be able to pull off my job successfully. I was also the happiest I had been in a long time.

While working at Fringe I met Cecilia, a company member with The Agency, who offered me a position as assistant stage manager for the company’s upcoming play about political corruption in Chicago, I Wish to Apologize to the People of Illinois. I spent the next several months working in a field that I was fairly green to and trying to absorb as much as I could. It was also the slow season for my freelance work so I existed almost entirely off of giant bags of licorice brought in by the show’s stage manager. I was hungry, cold (the transition from the Southwest to the Great Lakes region is not the easiest), and worried that I wouldn’t be able to pull off my job successfully. I was also the happiest I had been in a long time.

Luckily, I managed not to mess up too severely. You shouldn’t think that means I didn’t mess anything up—I could write a whole article on messing up in live theatre.

Wait, you know what, this is actually a great segue to talk about the fear of messing up and live theatre a little bit. See that? I called out my own segue (4th wall be damned). During those late nights of working on I Wish to Apologize I heard about this thing The Agency did called No Shame Theatre, a weekly theatrical open mic where the first 15 performers through the door get 5 minutes on stage. No Shame attracts writers, improvisers and sketch artists, fire eaters and magicians, standup comedians, musicians, and all manner of other performers.

The beautiful thing about No Shame is that it thrives in its brevity. What I mean is that each week is an entirely new show where each artist gets only a short window. You miss one week or step out of the room and you’ll never have the chance to see that content again. That brevity gives people the chance to try anything no matter the stage of development. In fact some of the best pieces I’ve seen were nothing more than a simple idea when the performers took to the stage. A short performance slot also means that whatever mistakes you make are short lived. In a way messing up or putting on a less-than-stellar performance is all part of the show. You learn, you grow, and you come back the next week with something new, something better.

The beautiful thing about No Shame is that it thrives in its brevity. What I mean is that each week is an entirely new show where each artist gets only a short window. You miss one week or step out of the room and you’ll never have the chance to see that content again. That brevity gives people the chance to try anything no matter the stage of development. In fact some of the best pieces I’ve seen were nothing more than a simple idea when the performers took to the stage. A short performance slot also means that whatever mistakes you make are short lived. In a way messing up or putting on a less-than-stellar performance is all part of the show. You learn, you grow, and you come back the next week with something new, something better.

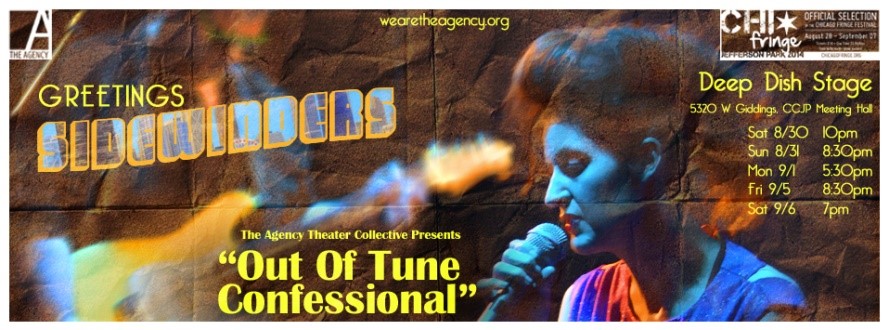

Another part of going to No Shame is getting to know its regulars, the diehard fans that come to and perform at nearly every show. One of these diehard performers, Ryan Brankin, is a composer/musician whose music struck a chord with The Agency. They approached Ryan about co-writing a show that would heavily feature his songs. Out of Tune Confessional was born. Part live concert, part drama, and part audience interaction Out of Tune made its way to the Chicago Fringe Festival as part of the 2014 line up—cue the opening number of the Disney movie about a lion prince who would be king.

Out of Tune also marked my second/third time (I also worked on At the Center this last Fall) working professionally with The Agency, this time as production manager. This granted me the ability to apply as a company member. I did so faster than I can count to ten and, not to brag, I can count to ten pretty quick. Luckily this was one Valentine that did not turn me down and I was voted into the company.

Out of Tune also marked my second/third time (I also worked on At the Center this last Fall) working professionally with The Agency, this time as production manager. This granted me the ability to apply as a company member. I did so faster than I can count to ten and, not to brag, I can count to ten pretty quick. Luckily this was one Valentine that did not turn me down and I was voted into the company.

Being part of a relatively new theatre company is exciting as I get to see its progression forward. Even in the short time I have been with The Agency our numbers have grown by around 25%. I know that sounds insidious (an agency with swelling numbers), but all joking aside it is extremely satisfying to see all these talented artists that we have worked with over this last season ask to join our company.

Another exciting prospect is getting to take a hand in the shaping of our company. This “past” winter (it is -3 as I write this, but surely it’s almost over…) I worked with several company members who helped me to implement a play reading series. Newly launched and titled the Chicago Reconnaissance Imperative the series will serve as a place to showcase and workshop upcoming Agency plays as well as give both established and new playwrights a place to hear their work read out loud by actors (an indispensable tool). I am currently helming this project as our company’s literary manager and I am looking forward to seeing where this and our other projects take our company in the future.

Another exciting prospect is getting to take a hand in the shaping of our company. This “past” winter (it is -3 as I write this, but surely it’s almost over…) I worked with several company members who helped me to implement a play reading series. Newly launched and titled the Chicago Reconnaissance Imperative the series will serve as a place to showcase and workshop upcoming Agency plays as well as give both established and new playwrights a place to hear their work read out loud by actors (an indispensable tool). I am currently helming this project as our company’s literary manager and I am looking forward to seeing where this and our other projects take our company in the future.

I know I took the long, meandering way of getting here, but (aside from that being my nature) I think that it gives a small glimpse into how theatre is made. How easily ideas, dedication, and people step from one project to the next and, in turn, how those artists and artistic endeavors grow.