Colomba Klenner is a Boston-based painter and illustrator, pursuing a Painting Bachelors of Fine Arts at Massachusetts College of Art and Design. She was born in Santiago, Chile but spent a large amount of time in Singapore before settling in Boston to pursue her career. Living in such contrasting places has allowed her art to be influenced by a variety of cultures and physical environments. Colomba’s art explores natural elements such as animals, plants, fungi and even microfauna. In October 2023, her first solo exhibition, “Microscopic” was exhibited at the Banana Gallery in Boston, Massachusetts.

Charlise Bar-Shai: What made you want to become an artist?

Colomba Klenner: It took me a long time to realize that being an artist was possible. I have been drawing, painting, and making my whole life. Yet being a professional artist seemed like a pipe dream. I instead chose the “less risky” path of becoming a makeup artist instead, while living in Singapore. I got certified as an MUA but my career was short-lived. I found MassArt in 2019 and visiting Boston was incredibly inspiring to me. There is art in every corner of this city and it showed me that a career in visual arts was absolutely possible and even encouraged.

CB: I saw on your website that you’ve lived in Chile, Singapore, and the United States. Your body of work is very diverse and shows that you have a lot of influences. How has living in each location shaped your art?

CK: I am very drawn to organic subjects. As such my biggest influences from all the countries I’ve lived in present themselves in plants, flowers and fruits. For example, Singapore has incredible fruits and flowers I had never seen or heard of before because I had never been in the tropics. Because of Singapore, I am fascinated by orchids. They now present themselves in my work either literally or within my color palettes and shapes. It’s like that for all the countries I’ve lived in. I keep pictures of things that inspire me in folders and there are a vast amount of pictures of the South of Chile, Singapore and the Acadia National Park in Maine. Whenever I need inspiration I look at these little mood boards I’ve created for myself and pick elements and colors that I can adapt into my own practice.

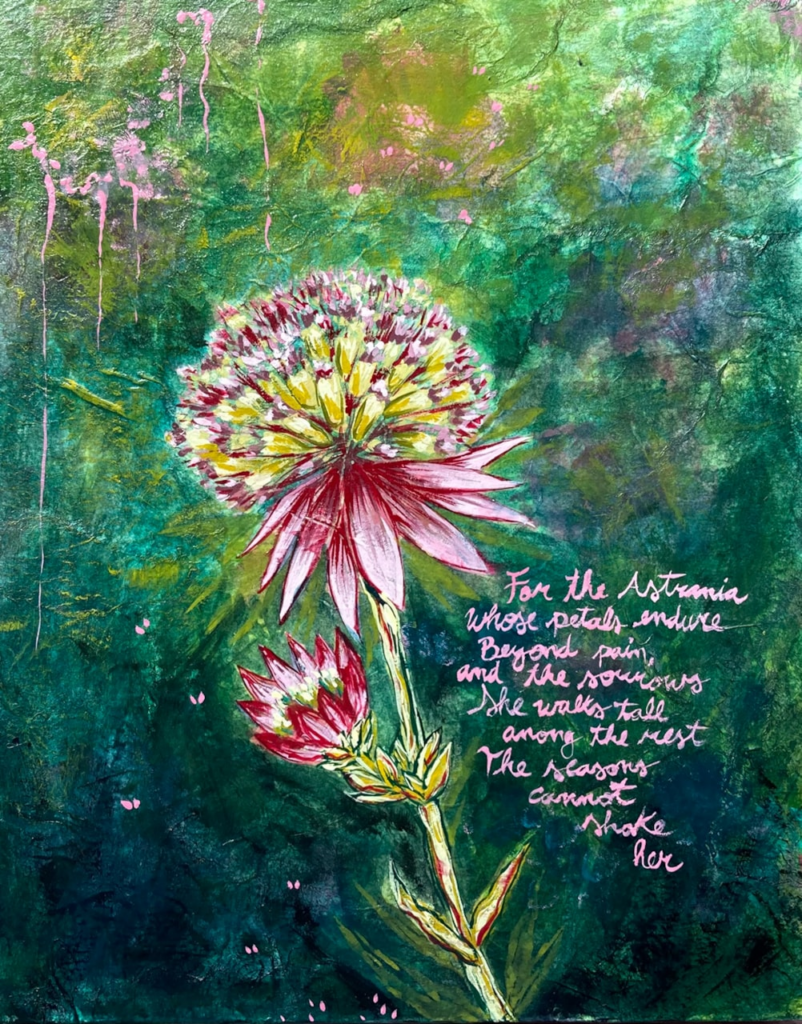

CB: I want to say that I love your usage of contrasting colors, like in your pieces “Pixie Cup” and “Astrana.” How do you decide what colors you want to select for your pieces? Do you have a particular mood or tone you like to use color to achieve?

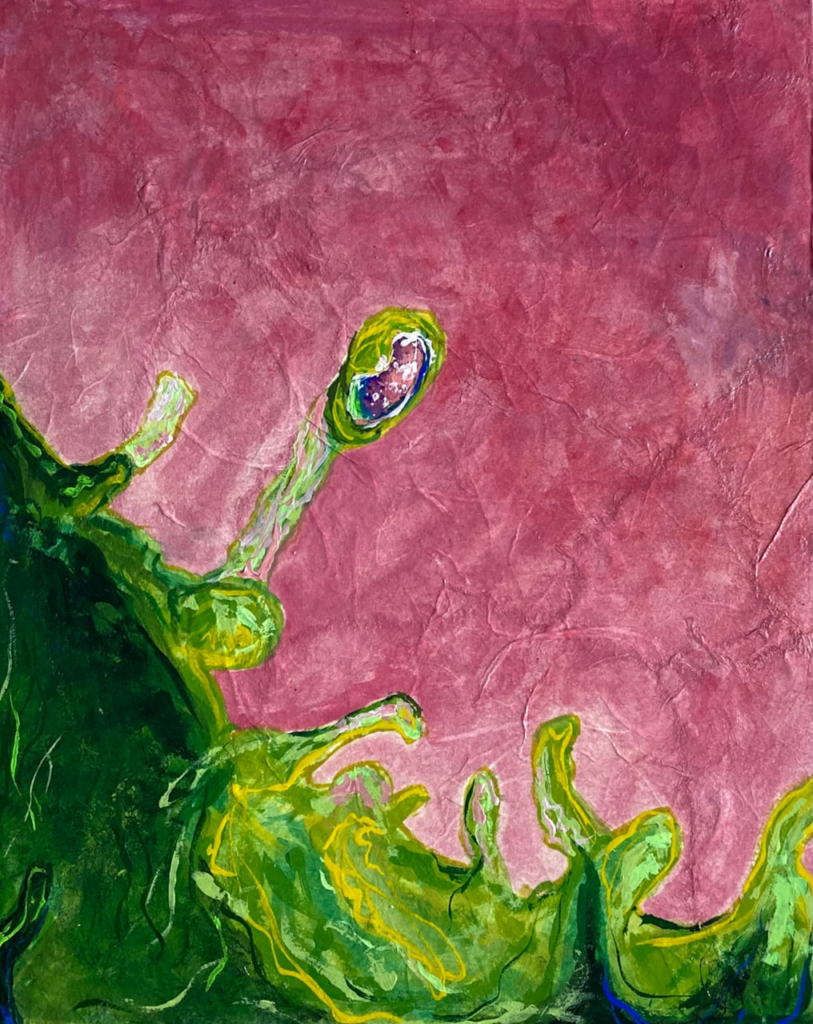

CK: Thank you, color theory is one of the most useful things I learned in art school. Most of the decisions that I make, including my color palettes, are carefully thought through. I do color studies for more complex pieces where I test out how using certain colors will impact the composition of my paintings. Mood is a big part of it too when I do color studies. Sometimes I may think “I want to make this in red, because it’s passionate” but it turns out when I do the color study it looks angry, so I know to change it to a pink. I think about what I want to covey and test it out. While all that is true and part of my process, there are certain color palettes I’m just naturally drawn to. I love green, as you can see in both “Pixie Cup” and “Astrana”, I love analogues cool color palettes (such as blue, purple, pink), and I love limited color palettes.

CB: I’d like to talk a bit about your “Microscopic” series. I’m really in love with your approach and how unique the subject matter is. Can you describe what your process was for creating these pieces?

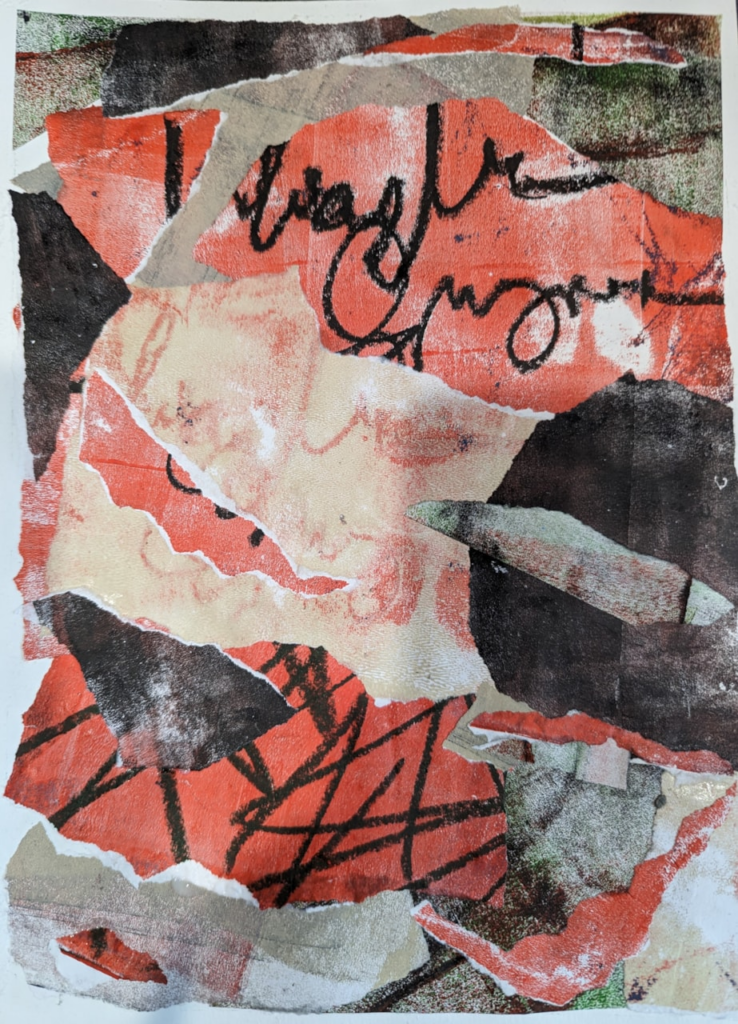

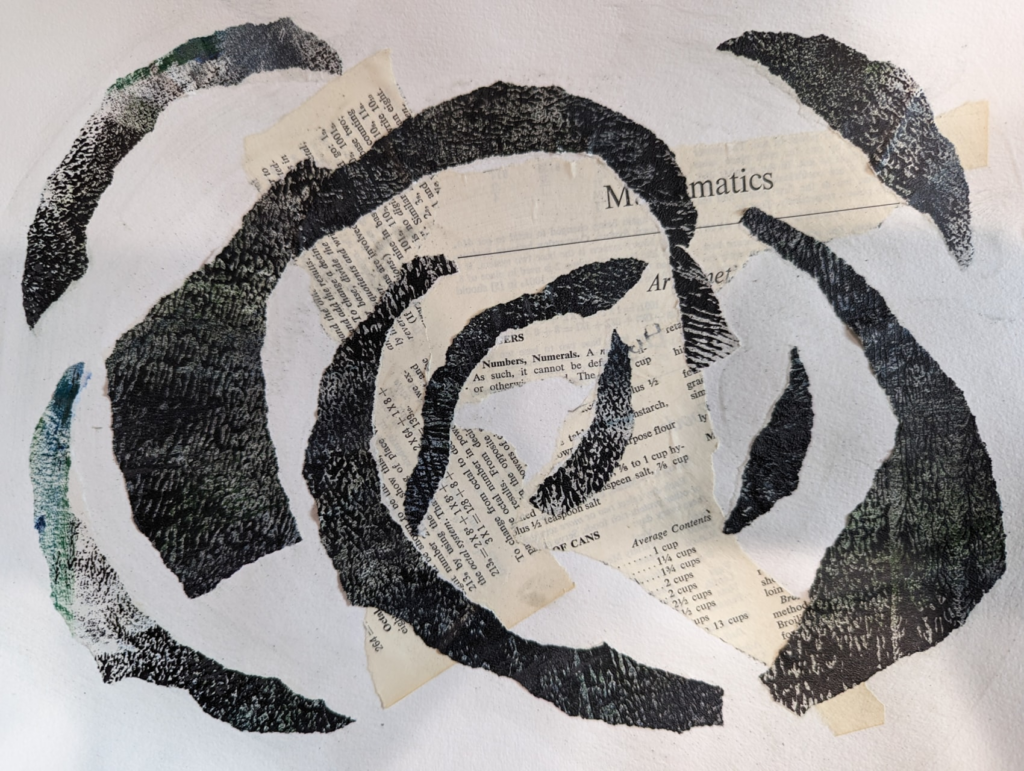

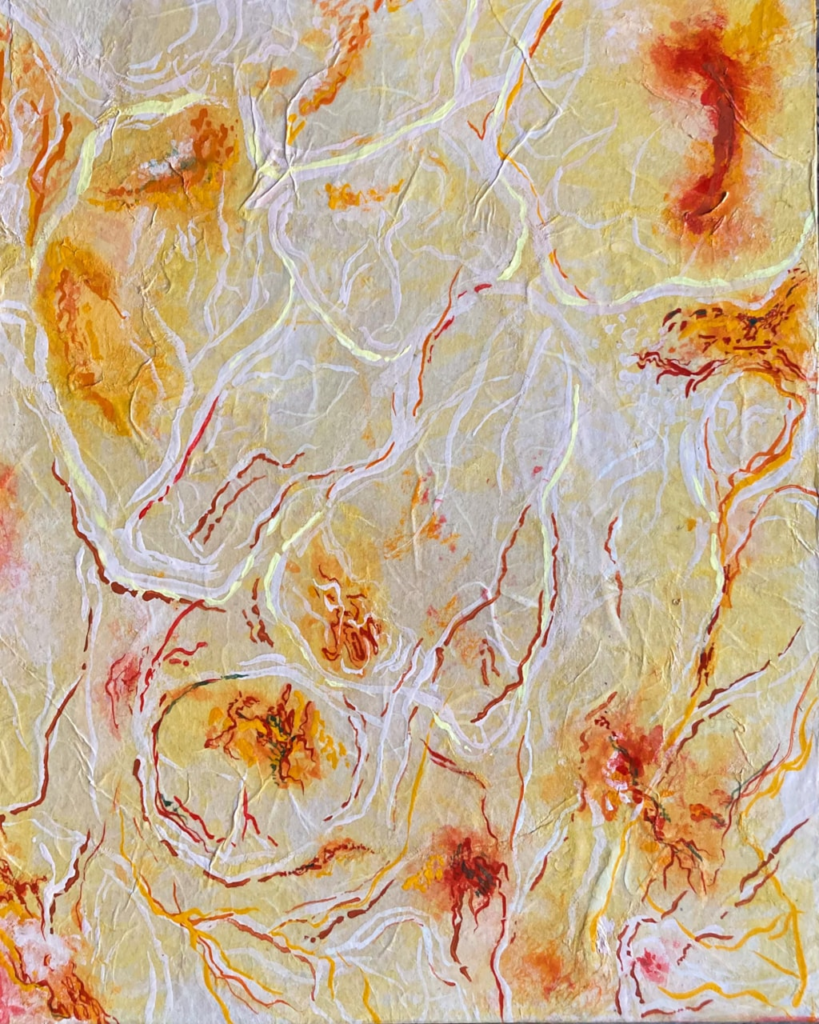

CK: I really appreciate that. I’ve been working on “Microscopic” for about a year. When I started this collection it was just me playing around because I had seen a kiwi under a microscope and thought it was fascinating. I had a strong desire to paint it and was very intrigued. I later got interest from someone who wanted to buy that first painting and that’s when I figured out that if I enjoy doing it and people are interested, these pieces could become a collection or a larger project. That’s when I went out and bought a microscope and the real fun started. My process for the pieces is as follows: I go out into the world and find something I love. A mushroom, a flower, anything that intrigues me. I take a thin sample of whatever material I found on a microscope slide and I examine it thoroughly under my microscope. I record that process and go back later to find references of interesting colors, compositions and textures. I then start preparing to paint. I get a wood panel and cover it with mulberry paper first, this is an important step to create texture and a more visually interesting painting. Finally, I’m ready to start the actual painting.

CB: Speaking of “Microscopic” series. I saw that was your first solo exhibition last month. First, I want to say congratulations. Secondly, what was it like having a solo exhibition for the first time? Was it scary? Exciting?

CK: Thank you so much! Having my first solo exhibition was so exciting! And also scary, and also a little difficult. I had been in group shows before but a solo show proved to be very different. First, I had to handle all the curating and reception details by myself. I created the poster for the show, made some flyers and put the word out myself. I’m confident in my work and created work that I can say I truly love and I am truly proud, but that’s why it was scary. What if no one came? What if people didn’t like it? Am I completely delusional? Ultimately it was a success and some pieces sold. I had a lot of fun listening to people tell me which were their favorites and why. I look forward to putting “Microscopic” with additional pieces in another gallery someday and to plan the exhibit for my (still unreleased) new body of work sometime next year.

CB: What has been the biggest challenge you’ve faced as an artist so far?

CK: My biggest challenge would probably be finding that balance between the financial aspects of being an artist with the creative process and creative vision. As someone doing this full-time now I have to worry about things like taxes and the business side of being a practicing artist which is often not taught. There is also the other side which is that you have to make a living and get your work out there, the creative vision might get compromised because it’s up to someone else if it gets shown. My first solo exhibition proposal was “Sea Life” and it focused on an environmental criticism of the fishing industry. That didn’t take off perhaps because it was too controversial. I’m sure I will find the right gallery to show that work in due time. In the meantime I had “Microscopic” which wasn’t trying to criticize or educate but rather show observations that I found fascinating and thought the public would too. It is something to think about when doing creative work.