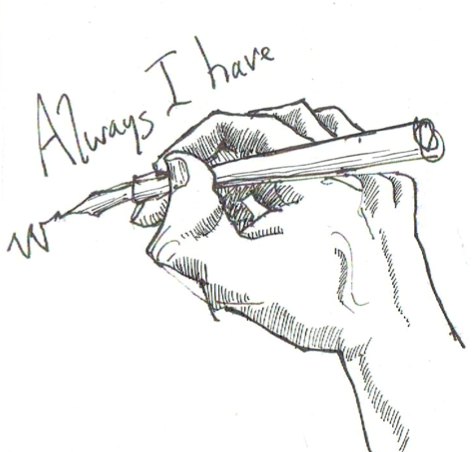

(Always I have w)anted to write, and always I have thought it would be natural to include images with text. As a child, in common with most kids, I was brought up on picture books, especially (being half-French) the adventures of Tintin and Astérix and the serial comics in their respective magazines. Children don’t have the bulkheads and prejudices of adults—instinctively they consider all avenues of expression to be equal and available to mingle: mud pies, finger-paints, drawings, words, rhyme, paper, leaves, glue, all borrow from each other and can be co-opted into the final whole. Adults making books for the juvenile readers’ market therefore put words and text together, and children happily go along with this syncretism, years after they know how to read, and no longer need a picture of a locomotive to learn the word for “train”.

(Always I have w)anted to write, and always I have thought it would be natural to include images with text. As a child, in common with most kids, I was brought up on picture books, especially (being half-French) the adventures of Tintin and Astérix and the serial comics in their respective magazines. Children don’t have the bulkheads and prejudices of adults—instinctively they consider all avenues of expression to be equal and available to mingle: mud pies, finger-paints, drawings, words, rhyme, paper, leaves, glue, all borrow from each other and can be co-opted into the final whole. Adults making books for the juvenile readers’ market therefore put words and text together, and children happily go along with this syncretism, years after they know how to read, and no longer need a picture of a locomotive to learn the word for “train”.

What’s surprising is not that I naturally read books with images as a boy, but that as an adult, and especially as the writer I became, I am still interested in reading novels with images, and in writing works of literary fiction or “creative non-fiction” that use images in interesting and useful ways.

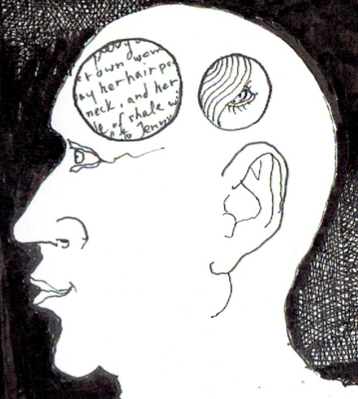

I will fine down the focus, since I’m not discussing graphic novels, which put as much narrative load on the images as they do on text; and while I have great respect for this genre, and enjoy Lloyd and Moore’s V for Vendetta, Enki Bilal’s work, and the collaborative mysteries of Léo Malet and Tardy, they are not what I do, they’re not what I’m interested in making. What I love, what I try to craft, are real, meaty novels (and non-fiction stories sometimes) that build complex worlds with words in the inimitable way that traditional novels do, co-opting a reader’s stored associations and memories, both conscious and non-, and employing them to build images in the mind: word-based images that, precisely because they do not provide specific illustration, draw on the symbols and pictures of the reader’s own life, and are therefore far more powerful and emotionally charged than any drawings an author could come up with.

This process must to some extent involve different areas of the brain from those which assimilate the fully formed images of others. What fascinates me, and perhaps this is a hangover from childhood, is the idea that words can and sometimes should include images to enhance the reading experience. (The argument is valid also for sounds, textures, smells and taste, though these are logistically harder to include in a book, so I won’t deal with them here.)

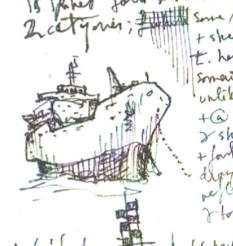

I’ve tried to insert images in a novel on several occasions, making elaborate pen-and-ink drawings of scenes, which ended up clashing with the narrative, either because they weren’t quite right for my idea of the character, or because they distracted from the thrust of text. The one novel where the process worked, sort of, was about a desperate magazine writer, and Conrad aficionado, who travels to south Asia to write an article about maritime piracy and, like Conrad’s Almayer or Lord Jim, becomes embroiled in and finally defeated by the world in which he at first found refuge. I used quick line drawings of ships and local watercraft I’d made while working on a similar article, and these seemed to mesh well with the story. Despite this small victory, South of Nowhere was never published. And most of the time my efforts at mixing text with images failed miserably.

I’ve tried to insert images in a novel on several occasions, making elaborate pen-and-ink drawings of scenes, which ended up clashing with the narrative, either because they weren’t quite right for my idea of the character, or because they distracted from the thrust of text. The one novel where the process worked, sort of, was about a desperate magazine writer, and Conrad aficionado, who travels to south Asia to write an article about maritime piracy and, like Conrad’s Almayer or Lord Jim, becomes embroiled in and finally defeated by the world in which he at first found refuge. I used quick line drawings of ships and local watercraft I’d made while working on a similar article, and these seemed to mesh well with the story. Despite this small victory, South of Nowhere was never published. And most of the time my efforts at mixing text with images failed miserably.

I turned to books I knew where images successfully enhanced the text, to understand where I might have gone wrong, and why that one unpublished novel seemed to work. I focused on six books—five novels and one slim volume which, to its credit, occupies an indefinable zone between poetry and non-fiction memoir. They were Time and Again by Jack Finney, The Collected Works of TS Spivet by Reif Larsen, Mickelsson’s Ghosts by John Gardner, City of Glass by Paul Auster, The Rings of Saturn by WG Sebald, and Bough Down by Karen Green.

Time and Again as its name implies is a time-travel novel, set in Manhattan, which includes actual photographs of period settings. The protagonist manages, by entering a stage-set full of artifacts from almost 100 years earlier, to go back to the 19th Century; he knows he has succeeded when he realizes the scene he saw of Central Park West (reproduced in the book) could not have included the perspective it did, had he not actually entered that era. The Rings of Saturn features an unnamed narrator walking around southeast England who, cued by features of the landscape, ruminates on time, death, the individual, and much else besides. (It is insulting and superficial to summarize a complex novel in this way, but if it inspires someone to check out Sebald, it’s worth doing.) The photographs—including images of a caged quail, a window with netting thrown over it, and bodies lined up under trees (at Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, apparently)—are blurry and vague and sadly, could be pictures of almost anywhere. In their bleakness and lack of sun, not to mention their dearth of specific referents, they reflect the narrator’s melancholia as he wanders among the relics of European history.

Paul Auster’s City of Glass is a metafictional detective novel, set in Manhattan, that includes a map and a sketch drawn by the protagonist which trace the movements of someone he is following; the illustrations reveal a message defined by those very movements.

The Collected Works of TS Spivet tells the story of a boy who skillfully sketches, diagrams and maps every detail of his life, from the flight of bats around his father’s ranch to his sister’s corn-shucking habits to the incidence of fast-food restaurants in Montana. Most of these charts and sketches are reproduced in the margins. Mickelsson’s Ghosts, John Gardner’s last novel, is the story of a college prof’s descent into madness, epiphany, or both, in rural Pennsylvania; scattered throughout are black-and-white photographs of windows and doorways, farm buildings in snow, offbeat compositions of ground cover.

Karen Green’s Bough Down consists of short, beautifully written, often dreamlike descriptions of the author’s state of mind following her husband’s suicide. The brief textual entries are accompanied by mixed-media images: washes of paint, pen-and-ink sketches, old postage stamps, scraps of typewritten text. The overall weft of found objects, of something cobbled together into balance, and of partial veiling (images and words are often blurred by pigment), meshes organically with the lost-and-found narrative that the reader traces through the book.

As I thought about these very different works, I realized they fell into two broad categories: mood, and clue. Time and Again and City of Glass both use images representing New York’s streets to help the reader understand a key development in the plot. The images in Mickelsson’s Ghosts, Bough Down and Rings of Saturn, on the other hand, have little or no evidentiary link to the story being told. The symbols etched upon the page are general, even abstract: windows, rain-washed blurry hills, vignettes of color and erasure, they could illustrate a completely different narrative. The images in Bough Down are particularly effective in conveying the longing for structure, and the structures of loss, implied in the collages and discernible words (“Why did you … the poor dogs. … Erase? OK.”)

TS Spivet falls between the two categories: some of the maps, diagrams and sketches provide evidence to help the reader accept the unlikely dénouement; at the same time, the skill, originality and obsession implied in his draughtmanship reflect a key component of the boy’s character.

Such categories are artificial; many novels with images, like Larsen’s, blur these distinctions, each in a unique way. But as guidelines for thought they must work well enough, for they allow me to understand that my earlier attempts at illustration failed because they were neither useful as clues, nor abstract enough to enhance mood without sabotaging the reader’s internal image-crafting process. Whereas South of Nowhere worked because the ships were almost abstractly rendered, freighters without crew or homeport, boats run by ghosts. Finally, the categories helped me avoid a mistake I was thinking of making, in a novel about a printmaker, by including examples of his art. I understand now I will have to restrict myself to vignettes: corners of an etching, or a sketch of his hand at work, similar to the one at the beginning of this post.