Brittney Corrigan is the author of the poetry collections Navigation, 40 Weeks, and most recently, Breaking, a chapbook responding to events in the news over the past several years. Daughters, a series of persona poems in the voices of daughters of various characters from folklore, mythology, and popular culture, is forthcoming from Airlie Press in September, 2021. Corrigan was raised in Colorado and has lived in Portland, Oregon for the past three decades, where she is an alumna and employee of Reed College. She is currently at work on her first short story collection and on a collection of poems about climate change and the Anthropocene age.

Brittney’s poem, “Whale Fall”, originally published in Thalia:

The ocean’s innumerable tiny mouths await the muffled impact like baby birds. Sediment clouds up at the deadened settling, and the flesh is set upon. How the weight of loss can be beautiful in its opening. Luminous worms undulate like party streamers as isopods and lobsters arrive to feast. This body holds an ecosystem unto itself: species found nowhere else but here, cleaved to the sunken remains. Sleeper sharks move in slow and gentle, ease the messy carcass to gleaming bones. And then, how the skeletal rafters of grief fuzz and bloom. How sometimes the coldest depths allow for such measured undoing. All the while hungry lives swarm and spread, come to stay. Limpets attach to the unhidden core. Sorrow in its abundance crushes, cycles, feeds. How the body rests, rich in what sustains.

Brittney’s poem, “Iteration”, originally published in Feral:

after the Aldabra rail One flightless bird evolves twice, before and after extinction. Collective bodies remember what it is to feel safe. You remember this, too. Before the world came lapping. A coral atoll—lagoon brimming with black-tipped sharks, no people—flourishes. Giant tortoises wander between turquoise worlds of sea and sky. The birds have no reason to fly away. A body with no enemies simplifies. There was a time when you didn’t need wings. Nothing is wasted. The birds push their long, ruddy necks through the coastal grass. Nothing chases them down. There was a time when you never looked behind you. The first time the ocean takes the island, every species on it goes extinct. A mass drowning. Thousands of years later, the water recedes. Fossils and sand surface; flora blooms. The bird’s white-throated cousins land on the shores. There was a time when your throat was open to the sky. The bird evolves again. Again relinquishes its wings. Again has no enemies. Again is a singular kind of being. You can do this, too. Sharks circle but can’t cross land. Bodies remold. Bodies wingless. Bones tell stories. Versions of stories. You recolonize your body. What it is to survive.

Brittney’s poem, “Rabbit, Rabbit, Rabbit”, originally published in The Wild Word:

The night a neighbor girl knocks on our door, baby rabbit in the bowl of her hands, I place it in a darkened box of straw, know it won’t make it to morning. My grandmother’s tradition for the first day of each month: stand at the edge of the bed upon waking, make a wish, yell Rabbit! Rabbit! Rabbit! and jump. Tiny rabbit body in my palm, soft and cold and still. Rabbit sitting on the moon, pestling herbs for the gods. A chant of white or grey rabbits to ward off smoke. The Black Rabbit of Inlé: his taking of this small life, his taking of my grandmother when I was still small. I must give this little un-rabbit back to the ground. Oh, to be so frightened that your heart cannot go on. But first, I must wake my young child. On this first of the month, I ease tangles separate through my hands. Sense something quivering just beneath what’s real as I leave the room. From down the hall, I hear the bedframe sigh. Little undone heart cupped in my hands. Little voice shouting a herd of rabbits onto the floorboards. I hop from foot to foot as they run past.

The following is an interview conducted on April 28, 2021, by Superstition Review‘s Poetry Editor, Carolina Quintero. It is in regards to Brittney’s works, writing process, and inspirations.

Carolina Quintero: Hello, Brittney! Thank you so much for agreeing to this interview with me. I really enjoyed reading your poetry. You have such a passion for animals and our environment and you put their importance into beautiful words. I also thought it was really striking and genius how you connect animal life to human life…Your writing frequently involves animals and the environment. What experiences or special interests have driven you to center your writing around this topic?

Brittney Corrigan: I’ve been drawn to animals and the natural world since I was a small child. I grew up in the gorgeous landscape of Colorado where my family spent a lot of time in the mountains and generally outdoors. And when I wasn’t playing outside or surrounded by a zoo’s worth of pets, I was watching episodes of Wild Kingdom. For years I wanted to become a marine biologist, drawn to the ocean and its creatures from my land-locked home. Though I’ve always felt connected with and protective of the environment, living in Oregon for the past three decades—with its wild coasts, wild animals, and wildfires—has strengthened that affinity and resolve. As the realities of climate change have made their way into my consciousness over the years—from my founding of an “environmental action club” in high school in the 1980s, to my love for the flora and fauna of the place where I live, to raising up my children in a world fraught with natural disasters and extinctions—I wanted to move toward action to preserve this planet and the life forms with which we share it, beginning with bringing awareness to these issues through my writing.

CQ: Your poems carry thorough knowledge about animals and ecosystems. What inspires you to learn about this?

BC: Voracious curiosity! I subscribe to countless email newsletters that showcase all things weird, wild, and wonderful (such as Atlas Obscura and National Geographic), and I love listening to podcasts of that ilk, as well (such as RadioLab and Ologies). I keep a running document of links to articles and oddities I find particularly fascinating that I come back to time and again to mine ideas for my work. In both my science-oriented poetry and my short fiction, the research is one of my favorite parts of the writing process. I love diving headlong into educating myself about a place or a species that I haven’t encountered before or that I just want to learn more about. In a high school English class, my teacher once presented me with a quote by Henry James: “Be one of the people on whom nothing is lost!” I carry that desire to notice, explore, and elucidate the world around me into my writing life.

CQ: What advocacy do you hope your poems will achieve? What audience do you hope your poems will reach?

BC: By bringing the plight of various ecosystems and species into my work, I hope to make what can seem like an overwhelming problem to tackle both particular and personal. I think if folks feel connected to the natural world and its creatures in specific, tangible ways, they will want to help and make change in small, meaningful ways. I hope that my poems reach folks of many interests, backgrounds, and generations and move them to learn more, and to do more, to combat climate change, extinction, and the effects of our current Anthropocene age.

CQ: What are your poetic influences as of late?

BC: My current favorite poets are Aimee Nezhukumatathil, Ada Limón, Ross Gay, Natalie Diaz, and Camille Dungy. I’m also enjoying reading essays on topics of extinction and the natural world by writers such as Michelle Nijhuis, Alison Hawthorne Deming, Elena Passarello, Linda Hogan, and Alexis Pauline Gumbs.

CQ: What advice would you give to young writers?

BC: I would say start with what you know and move outward toward your passions and ideas or topics you want to find out more about. First write for yourself, and then, when you are ready to share your writing with others, find your people. Seek out your fellow writers and readers with whom to share your work. Find a group of folks you trust and can share your roughest drafts with, and also find the mentors whose feedback will help your writing become stronger. And don’t be afraid to write outside of the boundaries you’ve been taught or the parameters you’ve been given. Break the rules and bust the genres open.

CQ: What are you currently working on in your writing?

BC: I recently completed a manuscript of poems about climate change, extinction, and the Anthropocene age. I’m now exploring those same topics in my first collection of short stories. As to poetry, I think science, ecology, and the natural world will always find their way into my work. I’m not sure exactly what’s next, but I’ve no doubt it will reveal itself to me, like bright animal eyes blinking out of the dark.

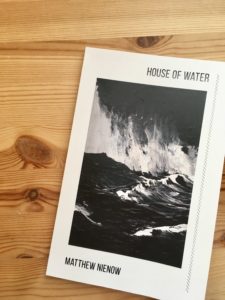

For the past few months I’ve been unmoored, I feel against everything. I think a lot of us do. During this time I’ve turned, as I always have in difficult times, to books. I’ve found myself drawn to two types of books, both of which seem relevant and necessary. The first kind are those that teach me to see through the eyes of others, show me the history of how we got here, give voice to the often unheard, teach me to resist, give me strength to fight back. The second type of book I’ve been drawn to are those which praise the physical world, look with wonder at the earth and its inhabitants, draw the eye to the light. The books of the first kind have been my maps and guides. The second kind of book has been an anchor for me. In these times of upheaval and uncertainty I am seeking things that ground me to the world, that re-invest me in this place. I want to hold something in my hands, to know that it is real, to remember I’m not against everything. The poems in Matthew Nienow’s

For the past few months I’ve been unmoored, I feel against everything. I think a lot of us do. During this time I’ve turned, as I always have in difficult times, to books. I’ve found myself drawn to two types of books, both of which seem relevant and necessary. The first kind are those that teach me to see through the eyes of others, show me the history of how we got here, give voice to the often unheard, teach me to resist, give me strength to fight back. The second type of book I’ve been drawn to are those which praise the physical world, look with wonder at the earth and its inhabitants, draw the eye to the light. The books of the first kind have been my maps and guides. The second kind of book has been an anchor for me. In these times of upheaval and uncertainty I am seeking things that ground me to the world, that re-invest me in this place. I want to hold something in my hands, to know that it is real, to remember I’m not against everything. The poems in Matthew Nienow’s