Brenna Fisher is an artist and early childhood educator interested in how artistic expression can be used to foster empathy, connection, and community. While teaching 3 and 4-year-olds in New York City, she collaborated to create a “compassionate curriculum” with the arts at its core such that students’ voices were heard and expressed through artistic expression. At Hunter College, her graduate research in Early Childhood Education delved into the ways drawing in particular could facilitate social justice work in early childhood settings. She is now continuing this research and her goal of supporting authentic and imaginative art practices by leading workshops with teachers in early childhood settings. Her introduction to teaching developed out of my experience as art director of Kingsley Pines Camp and then as a teaching artist at the Children’s Museum of the Arts in NYC.

Drawing and painting defined her time at the College of Wooster where she graduated with a B.A. in Studio Art and a minor in English. During this time Brenna’s artwork focused on the relationship between landscape and personal narrative. While at Wooster, she also participated in the New York Arts Program as an intern for Bruce Pearson, Nancy Bowen, and Daniel Zeller. Her experience with NYAP, and particularly with her mentor Emilie Clark, taught her how to sustain her art through any transition.

Superstition Review: How do you come up with ideas for your work?

Brenna Fisher: When I experience a strong feeling – either physical or mental – I need to draw or write in order to understand it, process it, and move through it. When I think about my mind and body I see it in colors, shapes, and lines. When you look at my art you are looking at me. Ideas for my art emerge while nursing my now five month old, during the deep breathing in a stretch, after a dream that lingers into the afternoon awake time, or during a conversation with a friend when I get the tingle of, “Oh, you feel that too.” One of the many mantras is Louise Bourgeois’ famous quote, “Art is a guarantee of sanity.” Another comes from Hannah Gadsby’s “Nanette,” “There is nothing stronger than a broken woman who has rebuilt herself.”

After college, I lost that artistic community, and during this time, journaling sustained my art practice as I learned how to create the structures I would need to nurture my art career. Once I found a fulfilling day job in teaching, my art started to grow in scale and concept. Working with young students re-engaged me and allowed me to let go enough to really flourish independently.

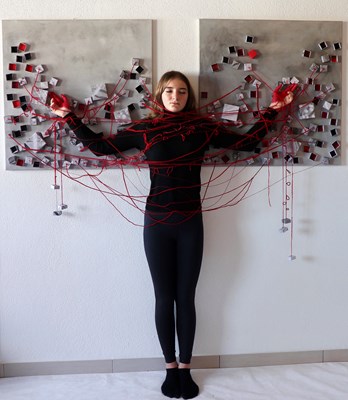

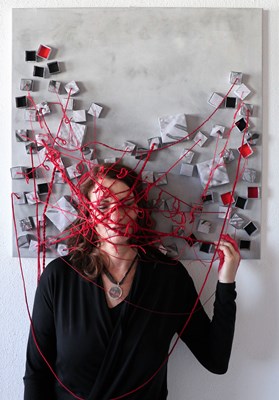

SR: In your most recent collection, “Sisterhood, Motherhood, “Krasnerhood” what was your process for creating each piece?

BF: Each piece in this ongoing collection is a window into a moment in my life that carried weight along my journey into motherhood. Right now, as the new mother to daughter born in the June of the pandemic, I am grappling with the way dichotic emotions can exist simultaneously: tension and release, love and grief, hope and fear, pain and joy. In each piece, these emotions battle each other for attention, find resolution, turn to mud, and marry each other as I visit my paintings during long evening or brief daytime sessions.

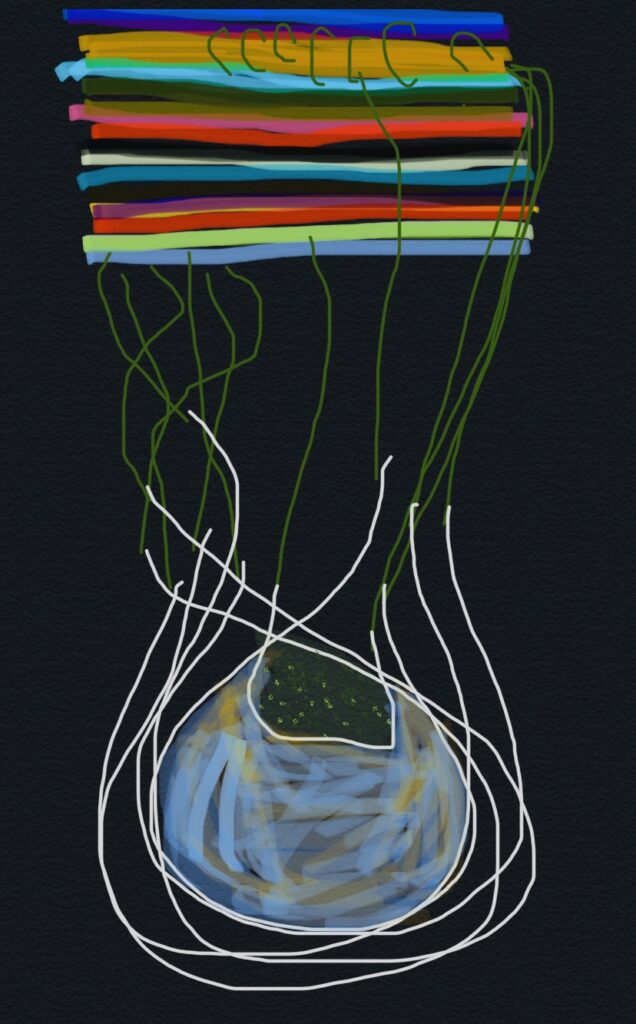

For a deeper look into my process I reflect on creating, “Sisterhood, Motherhood, Krasnernood,” the painting that this series is named for. I made this piece over the course of three months after my first pregnancy ended after 14 very hard weeks with the loss of a little girl. Shortly after this, my husband and I adopted a cat that we named Krasner after one of my favorite artists, Lee Krasner. That cat (whom the painting is partially named for) and this painting healed me. This painting, which is quite large, started on my desk, then moved to my wall, and then spent a long time on my floor where I worked on it while laying flat on the ground. As a result, Krasner the cat (at that time a kitten) ate portions of the paper, meandered through the green paint and dragged burnt sienna chalk pastel to places I might not have put it. She knew best however, as cats often do. While I painted I thought of the place where I put the rock I picked out for the girl I grew for 14 weeks and then grieved for (also depicted in “Where Jane’s Rock Lives”), I thought of the space in my body where another child might grow into, and I thought of all the women in my life – my sisterhood – who supported me and helped me feel strong and powerful even when I didn’t. This painting now lives with one of those women.

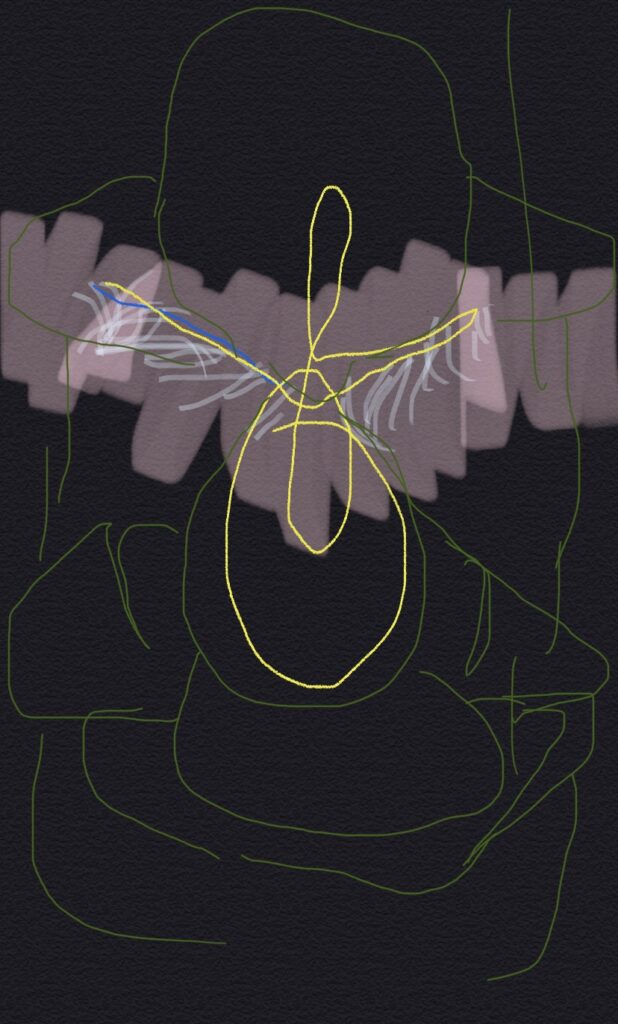

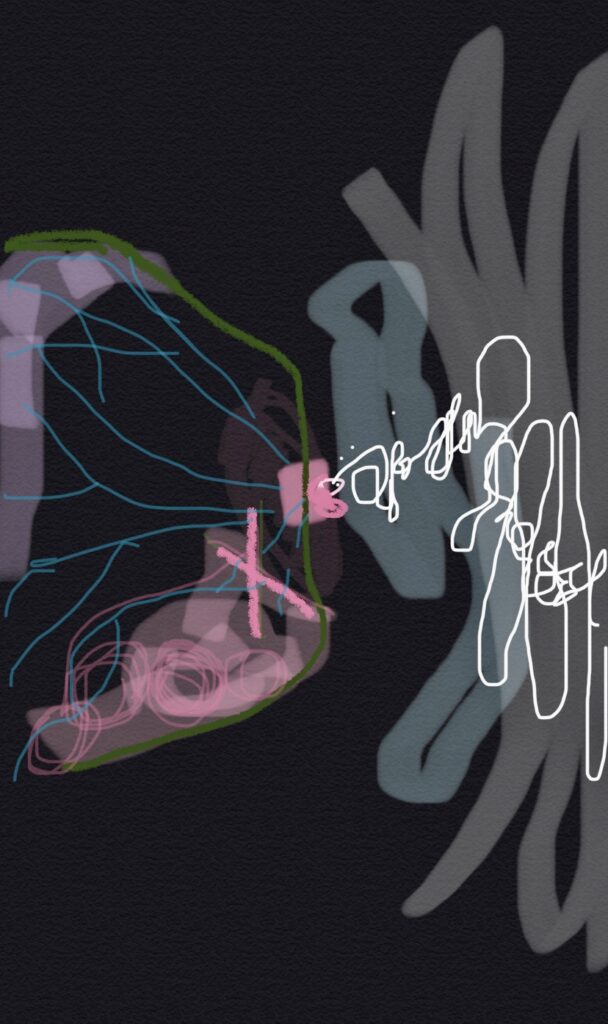

The more recent paintings in Sisterhood, Motherhood, Krasnerhood carry grief from that loss but also the fresh hope and fullness that comes from new motherhood. I made “You Smell Like Toasted Marshmallows,” while my daughter slept on my chest. This work feels like a triptych with the digital drawing, a poem, and a larger drawing currently in progress. I resisted the urge to use digital drawing for a long time because the choices available to me felt overwhelming. Now, after some experimentation I find it feels like a friendly blend of many of my favorite mediums including the between the urgency of drawing, the loss of control I find in watercolors, and the layering possibilities in oil paint.

SR: What does your physical workspace look like? What is one thing you have to have with you as you work?

BF: Ha! The top of my stoop in the sunlight, in my tub with my work taped to the shower wall, all over the dining room table, running the length of my bedroom….I make work when and where I can and as often as I can muster what I need to render myself in colors and lines. All of the digital drawings and writing I have made have been made in motion or with one hand wrapped around my child. But, then I also carve out time to return to these ideas and manifest them into larger works, which you can see in the digital drawing, “Tiny Seahorses” and its companion painting, “Tiny Seahorses that Live Inside my Left Breast.”

For a long time I had a studio in my home. Now, I carve out my workspace with the limitations of the pandemic, my husband working from home, and the enormity of space a baby takes up. I draw and write as much as I can and I have done everything I can to let go of any rules or definitive needs I had for making art. Virginia Woolf writes in A Room of One’s Own, “There is no gate, no lock, no bolt that you can set upon the freedom of my mind.” I had my own version of this when I was put in time out as a child: “You can’t put me in time out because I am having fun in my imagination.” It still feels true. When I sat with answering this question I pulled Virginia Woolf off the shelf and pieced through and felt tremendous solidarity with everyone in exactly my situation at home without a workspace right now but still resolutely making art because they know art matters deeply.

SR: How has the pandemic affected your art and process?

BF: During this time when my own sense of agency has shifted, I still feel whole and have the space I need to grapple and grow because I am determined to make and share my art. I am a more empathic and compassionate person because I am an artist. I feel empowered because I am an artist. Without art I know I would feel incredibly alone, afraid, and disconnected during this time.

When the pandemic hit, my career shifted. I am now at home full time making art and caring for my 5 month old daughter. Originally, my vision for this year looked very different. I had planned to continue teaching and to move into a new role as a studio teacher that would support the arts curriculum and work with individual students to use art as a problem solving tool. While it felt disappointing to let go of that position, one I had helped design myself and felt like a huge leap for my career, I have not let go of my art practice or my desire to connect with a broader community through art. Since the pandemic, I have opened myself up to others through social media and other digital platforms.

I am leaning into sharing the mucky, disgusting, or downright challenging parts of this experience and also hope to show how those parts exist in equal parts to the ecstatic moments, the wonder, and the bliss of a little face looking up at you. I have often described the process of making as a “thin space”; a space where the artist feels connected to herself and her world deeply.

SR: How is your work touched by social justice?

BF: I see myself as an artist-educator. I both seek to use art to understand myself as a form of auto-ethnographic research and also to make art more accessible to others.

Now, more than ever, art matters. The act of making and sharing art is an act of radical vulnerability and empathy. Through art, we can still see each other when half of our faces have to be covered in order to protect each other. There are a lot of causes and stories that matter, but the only one I can tell is my own.

I truly believe that art changes lives. I believe that art is the best form of self-reflection and self-discovery that we have available to us. But in the same way that authentic play is often missing more and more from early childhood classrooms, I’ve noticed how often children’s art looks the same when made in school. These experiences often drive people away from making something because we’re only taught to replicate an artist’s style rather than how to trust our vision, practice a skill in order to manifest what we imagine, process our feelings of discomfort inherent in creation, and finally to take the brave step to share our work, receive criticism, and return to ourselves again. I think everyone has a desire to create something that is truly unique to themselves and have that part of themselves be heard, but we either tell ourselves no one needs our story or that we aren’t talented enough to tell it ourselves. I’m eager to change the conversation around art from what something looks like towards why someone made it, how they made it, and most importantly to center it around their story. All I have is the story that belongs to me and a willingness to listen to the stories of others.

SR: Do you have any upcoming projects or work you would like to discuss?

BF: Over this year I am continuing to build this series and hope to show the work from this first year of motherhood either in person or digitally depending on the way the world manifests. I’m continuing to explore digital art making as a medium and playing with the relationship between my drawing, writing, and painting. I am compiling my writing and art into a show or installation that takes my process and invites others into it to share their stories. In this time when the scale of my work has shrunk, the aspirations for my work have grown and I am looking for opportunities to paint on a bigger scale, create sculpture, and invest time into the work of sharing and revisiting my work as it expands.