An old friend who was passing through Des Moines dropped by for a visit. This was about seven years ago. I was living at the time in a Fifties-era ranch house near the Firestone plant and I-80, in a dense residential area where nevertheless a mountain lion was killed a few years later within blocks of my children’s school.

On this particular afternoon my wife was out looking at paint or carpet samples—we’d just bought the house and were still in the process of renovating—and had left me in charge of our one year old. I picked him up when he cried, set him down when he cried harder, warmed a bottle, changed a diaper, made sure the safety gates were in place. From the look on my friend’s face, I could tell he was nervous around the child and casting about for an excuse to leave. We were discussing books, and he asked what my favorite short story was. I answered without thinking that it was Raymond Carver’s “Cathedral.”

My friend and I had met in grad school. We were actually more like acquaintances, sharing a few friends and seminar courses in common, crossing paths now and then, but early on we’d identified one another as readers. My friend, in fact, was sort of a pleasant-natured, unassuming polymath, dazzling in his range of references. Once I stopped by to find him sitting on the couch, the little wheeled table beside him cluttered with books borrowed from the university library. He had three or four open and appeared to be reading from them simultaneously, this while a film played on TV. A stack of video cases lay scattered on the carpet. His consumption of cultural artifacts—books, music, films—wasn’t systematic, it was ravenous.

So it made sense that my answer disappointed him. “Cathedral” was to many an anthology story, a learner’s story, a bike with training wheels.

“That story just seems a little…pat, don’t you think?”

“Well,” I said, articulate as always, “sure, I mean, um, I can see how you might, uh, draw that conclusion.” We talked a little while longer, though not much more was said about Carver.

Only one other memory from that afternoon remains, my friend’s offhand remark that I was “probably one of those people who gets up and writes for an hour every morning before work.” He had a quick, easy laugh, and even his serious comments were made with a half-smile that caused you to question his sincerity. And so he made the statement seem lighthearted, a joke, but every sentence that begins with you’re probably one of those people ends up denigrating you and the rest of those people.

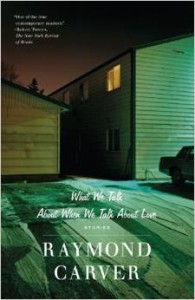

Needless to say, he’d inserted the IV and the self-doubt was flowing on a steady drip. Maybe “Cathedral” was a paint-by-numbers story. Recently I read an essay of John Updike’s in which he lumped Carver together as a practitioner of various “minimalisms” with Donald Barthelme, Angela Carter, and Kurt Vonnegut. In Updike’s view, “These writers wrote out of a certain late-twentieth-century mood of burn-out, of humorous anti-romanticism; how much “point” will be left when that mood has evaporated?” Carver was regularly labeled a minimalist, thanks to Gordon Lish’s cuts to his early stories—and here the word “cuts” perhaps understates the point. They were more like disembowelments. I think it’s safe to say, now that we’ve seen the stories as Carver intended them, that he wasn’t a minimalist, at least not in the manner of, say, Diane Williams or Lydia Davis.

Is minimalism even inherently a bad thing? Maybe only when you preface it with you’re probably one of those people. Carver seemed to bristle at the term, perhaps because he felt he’d been unfairly ghettoized, or perhaps it had something to do with his relationship with Lish—the embarrassment of allowing himself to be bullied.

The whole thing about Carver and minimalism and Lish has passed over into the realm of folklore. In the recently published MFA Vs. NYC, it seems that either Carver or Lish is mentioned in every essay, as though this entire generation of fiction writers has either worn Carver like an albatross around the neck or held him up as a patron saint. His effect on workshops and “MFA fiction” has been pervasive. The old tale about he and Cheever in Iowa City waiting one morning for the liquor store to open is repeated like gospel. In MFA Vs. NYC a former student of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop even describes the liquor store as though it were some kind of pilgrimage site.

Updike’s other charge—beyond Raymond Carver being one of those minimalists—is more damning. Carver (and Barthelme, Carter, and Vonnegut) evoke in their work a particular tone or mood specific to the late twentieth-century, and once this mood evaporates, the writing will survive, if at all, merely as an anachronism, a testament to a bygone period. Of course the same could be said of Main Street or The Great Gatsby. Literary documents capture the pulse of a particular period more effectively than land deeds or census records. They may not give us data, but they give us the modes of speech and the cut of the clothes. Carver gives us the dirty realism of the Seventies and early Eighties, just as Updike gave us his account of the late Sixties free love movement in Couples. (And readers of Couples might argue that it could’ve benefited from a bit more minimalism.)

“Cathedral” is Carver’s most anthologized story, the one most often taken to represent his full body of work. It’s oftentimes the reader’s first hit of Carver, the gateway drug. I wouldn’t use such a metaphor if pot-smoking didn’t figure so prevalently in the story. If you recall, the narrator of “Cathedral” rolls a couple postprandial joints after his wife has retired upstairs. At this point, he’s still ambivalent about his houseguest (“I didn’t want to be left alone with a blind man,” he says) but the marijuana represents a turning point. When the narrator places one of the joints in Robert’s fingers, it’s the first time the two touch, apart from shaking hands on their first introduction. There’s an interesting physicality to the exchange. Robert’s openness to trying the drug is also revelatory to the narrator, who is mired in closed-off resistance, with a job he hates and anxiety-laden dreams. The narrator never goes to sleep with his wife but instead stays up as late as possible, narcotizing himself.

The main problem we have these days with “Cathedral” is not necessarily the story but rather its familiarity to us as readers. “Cathedral” depends for its success on the surprising bond that forms in the end between the blind man and the narrator. In that regard, it’s a little like an O’Henry story. Once we’ve seen how the magic trick works, it’s not quite so magical anymore. So is it still possible to love “Cathedral” once we’ve learned how the assistant gets sawn in half?

II.

Back when we were in grad school, my classmate—the one I mentioned earlier—seemed shadowy and insubstantial; not aloof, exactly, just set apart from the tribe. Most of the students in the program were single. All of them stayed within a few miles of campus but my friend lived five hours away, commuting back and forth from Columbus, where his wife, whom none of us had met, was in med school. In her spare time, she did abstract paintings that were apparently highly salable. My classmate explained once how his wife designed the canvases while someone else did the actual painting. It was all a little confusing to me.

I tried not to make comparisons to my own wife, who grew up in the small town neighboring mine. Her father worked at the Firestone plant; my father painted ammonia tanks and stock-car frames for a living. My wife and I met at a gathering, which was a nice way of saying some kids got together one night to drink beer. She was in high school, cutting classes and occasionally shoplifting clothes from the mall. I was busy flunking out of my freshman year at Iowa. So maybe it’s apparent why Carver appealed to me in those days. Some readers approached his characters as though they were exotic zoo animals, but they never seemed all that unusual to me.

My friend’s writing was excellent. It had a polish and complexity to it that made ours appear rudimentary by contrast. Yet I started to get the impression he was just pulling the same worn manuscript from his drawer each semester and dusting it off for workshop. It was the same manuscript he’d submitted for entry to the program, the same novel fragment that won him a fellowship. For all his obvious and intimidating skill, he suffered from a disinclination to finish the thing and send it out. He would never be one of those writers who got up early to write for an hour before heading off to work. I suppose I may have been, but it didn’t much matter because I suffered from a different malady, flitting from project to project without ever finishing anything, the writer’s version of ADD.

I didn’t bother rereading “Cathedral” after my conversation with my classmate. I imagine he expected me to name something by Borges or Calvino, and in the years since his visit my tastes have taken a turn. I’ve come to regard certain realist fiction, like certain realist or photo-realist paintings, as an exercise in technique, lacking in imagination. Maybe this coincides with the birth of my kids and all the children’s books we’ve read together, where creativity is celebrated and the imagination provides a means of escape.

So when I recently reread “Cathedral,” I did so with a cringe, uncertain of what I might find. We paint these landmarks of our past with a rosy-hued nostalgia. How would I feel about Interview with the Vampire and The Stand if I returned to them today? How well a story ages says something about the story but also something about the reader. When I was nineteen, I hung out with a group of friends who’d grown increasingly preoccupied with getting fucked up. This was how I came to pass much of my freshman year—in a fog—which isn’t so unusual, particularly at a place like Iowa. My friends also happened to be readers, and when we weren’t drinking ourselves into stupors we were passing dog-eared books back and forth, heavily invested in the subgenre of literary debauchery. Most of the Beats fell into this category. Bukowski was revered, along with Jim Carroll, Denis Johnson, Hunter S. Thompson, Bret Easton Ellis. You can find these same names today on the shelves of nineteen year-olds looking for something shocking and subversive. I suppose Chuck Palahniuk would now be the ringleader of such a club. To the list I added Raymond Carver. I read his stories for the lurid details, never realizing they were meant as cautionary tales. The tragic characters struck me, perversely, as comical. At age nineteen I had never witnessed a marriage unraveling or a true alcoholic, as I later would, someone with a terrible disease who went into treatment and came out looking frazzled after shock therapy and Antabuse.

III.

The other day I listened to a New Yorker podcast of Thomas McGuane reading James Salter’s fantastic story “Last Night,” and McGuane commented that many of the best stories start with big risks. This, I think, is true of “Cathedral.” Rather than choosing the wife’s perspective or even Robert’s, Carver tells the story through the husband’s “eyes”—paradoxically, since the husband suffers from a kind of emotional or empathetic blindness. Either the wife or Robert would’ve been more sympathetic narrators, but then we would’ve lost all the husband’s interiority, for he rarely voices his fear and envy of the blind man other than to make a racist remark about Robert’s recently deceased wife.

There’s an ugliness to the husband’s account that Carver must’ve known might repel his readers, and it starts in the opening paragraph when he points out Robert’s disability, also noting that Robert is his wife’s friend, not his. But Carver doesn’t drive the point home until the final sentence of the opening paragraph: “A blind man in my house was not something I looked forward to.” Few lines carry as much weight as this one. With a few quick strokes Carver establishes the story’s point of view, conflict, and tone, one that might best be described as passive-aggressive. The narrator doesn’t say “I didn’t want the blind man in my house,” which would be far too straightforward for such a study in repression. The sentence implies he has already accepted the blind man’s arrival. The passive sentence construction mimics the narrator’s passive state.

Carver sets events in motion—the advent of the blind man’s arrival—and then starts building the tension a line at a time, the way the cathedral on TV is constructed and later re-envisioned on paper. Carver’s sentences are short, declarative, reminiscent of Hemingway, who also seemed to specialize in narrative compression and repression. In his essay “Fires,” Carver acknowledges that his writing has been compared to Hemingway’s, though he doesn’t go so far as to say that Hemingway was a guiding influence. The distinction in “Cathedral” is that these are the first-person thoughts of a narrator who has difficulty expressing himself. The sentence structure mirrors his ennui. He’s tired of hearing about the blind man, how Robert ran his fingers over the wife’s face on their final day working together. Of course this is envy in disguise, which comes through again when the narrator describes the cassette tapes mailed back and forth between the wife and Robert, the intimacy of the conversations. The narrator is at turns bored, jealous, affronted, and judgmental, and his preconceptions about Robert threaten to spoil their first encounter.

Reading that opening section of “Cathedral” is like driving past a car wreck. We don’t want to see it and we can’t turn away. But the story is different than some of Carver’s earlier work, where the characters seem beyond saving, casualties of circumstances or their own bad choices. “Cathedral” could’ve followed its initial arc, the antipathy growing worse when the narrator met Robert until finally becoming unsustainable, presumably ending in the narrator’s failure to move beyond his own jealousy and preconceptions. Instead, ice starts to melt. The tension deflates, and what we end up with is a story of forged connections. The building of the cathedral signifies the narrator’s link with another human being.

Once you start looking at “Cathedral,” you see how unorthodox it really is. First, there’s that issue of tension. Freytag tells us we need to draw the conflict out as long as possible, but in Carver’s story it starts dissolving midway through. And there’s also all the exposition—Robert’s backstory and the circumstances leading him to the narrator’s house—frontloaded into “Cathedral.” Hemingway wouldn’t have done that. He would’ve viewed it as the portion of the iceberg meant to remain submerged. The exposition here could be seen as the narrator’s preconceived notions of the blind man: a monochromatic view. An interesting exchange takes place in the story when the narrator’s wife asks Robert if he has a TV. Robert responds that he has two—a black and white set and a color model—but he always turns on the color TV. This coincides, not incidentally, with the way the narrator has begun to view Robert. His observations grow more vivid.

In his essay in MFA Vs. NYC, Fredric Jameson makes note of Carver’s “lower-middle class minimalism.” He appears to use the terms “minimalist” and “miniaturist” interchangeably, but it seems that minimalism—as proposed by Hemingway or Lish, anyway—is a method of purposeful exclusion, while miniaturism involves an intense focus on a tiny area. Jameson likens it to model trains, where no detail is left out, and claims the miniaturist is therefore also a maximalist. Faulkner and his postage stamp of native soil is the example used. It’s hard to trace Carver back to Faulkner, but you can see the miniaturist impulse at work in the latter half of “Cathedral,” the Technicolor section in which the narrator has a chance to observe the blind man in person. “Cathedral” is a longish story that takes place over the course of a single evening in a single setting. It’s amazing how kinetic the story is, considering its external events, which essentially are these: three people eat a huge meal and lounge around afterwards. One gets tired and goes to bed while the other two watch TV.

The narrator mentions the way Robert touches his suitcase, “taking his bearings,” and later makes special note of the blind man’s eating habits, the way his eyes look, how he lifts his beard and lets it fall. His observations of Robert humanize him, the irony of course being that the narrator, blind this whole time, finally starts to see clearly at the end when his eyes are squeezed shut. In “Fires,” Carver describes his minimalism as being incidental, the byproduct of a poor memory for details.

IV.

My neighborhood was full of mature sycamore and locust trees, leaves swirling around untended yards. There were a lot of chained-up dogs, for sale or foreclosure signs, Harleys parked in front of tiny houses. We moved in at the height of the real estate bubble when prices were monumentally overinflated. Like every other new homebuyer, we fully expected to sell the house quickly and use the profits to upgrade before our kids reached school age. Then the bubble burst and we got mired in the La Brea of an underwater mortgage. We tried multiple realtors. We looked into rental schemes. We considered private schools (too expensive). We tried open enrolling and were turned down by our district due to our “socioeconomic status,” a euphemistic way of saying we were white and made too much money. The suggestion of our income would’ve been laughable if it weren’t so frustrating, because the truth was that between our mortgage and student loans, our car payments and credit cards and bills, we were pretty well broke.

We sent our kids to the local elementary in what felt like an awful surrender. We were heartsick with failure. Our school district was the worst in the city, possibly the worst in the state. There were bright spots—wonderful, dedicated, passionate teachers—but there were also a pronounced lack of resources and a large number of students for whom English was a second language. We showed up for our first orientation to find the doors locked. It was a janitor who finally notified us the orientation had been cancelled due to construction work at the school. The parents stood on the hot sidewalk outside, holding bags full of pencils and Kleenex and glue sticks. My wife started crying.

But you keep going, you keep trying, you make the best of things. Your house sits on the market. You drop the price. Then on a crisp fall morning, while you’re at work and your kids are in school, you find out a mountain lion has been roaming your neighborhood. The nearest mountains are twelve hours away. At this point the situation truly does become laughable. It would be disingenuous to call it a last straw because there have already been last straws. This is just another in a series of unlikely events you can’t quite comprehend. The cougar was spotted near the elementary, and the kids were brought in from recess. Deputies cornered the animal among some houses about a block and a half from yours. They shot and killed it, and the mountain lion was stuffed and placed on display in the DNR building at the state fairgrounds. People filed past with their corndogs and funnel cakes to take a look.

V.

I have three novels in various drafts, though I’d be lying to say any of them is anywhere near completion. Occasionally I’ll open one of the files and tinker for a week or so until the hopelessness of the effort becomes overwhelming. I blame this on my compulsion to hop from project to project, the same sickness that causes me to spend my time shopping for new books when there’s already a tottering stack on my nightstand. My suspicion is that I’ve always had this “illness” but that it long remained latent, buried like a cicada that emerges after seventeen years to make a lot of racket. My brother, as a teen and young adult, started collecting LPs, comic books, pulp paperbacks, baseball cards, even box top cereal prizes, and when I came of age I was similarly obsessive in the way I accumulated books, CDs, and movies. These items became an outward manifestation of my intellectual insecurities but also served for me—and for my brother, I think—as a protective boundary. For two people who grew up with few possessions, gathering stuff around us made us feel secure.

Whatever its root causes, my flightiness is what will likely make me, forevermore, a writer of poems and short stories. When I was nineteen, a freshman at Iowa, I was drawn to Raymond Carver and Denis Johnson because they wrote about the downtrodden and irremediably fucked-up (adjectives I gladly self-applied at the time). Both authors had haunted Iowa City; both wrote poems and short stories. Carver, in “Fires,” blames his own turn toward poetry and short stories on parenting, claiming he never had the sustained period of time necessary to work on anything longer.

I always had it in my mind that “Cathedral” was my favorite short story, but the truth is that after I worked my way through Carver’s fiction as a student, I never returned to it. This was because I came to sour on Carver the person, as separate from his work. I realize it’s unfair and judgmental of me to say that, but after reading “Fires” I can’t help it; I simply lost interest.

VI.

I didn’t have children of my own when I first read “Fires,” but I still recall my feeling of slack-jawed shock on that initial pass-through. This was an essay purporting to be about Carver’s influences but was truly just a diatribe about his kids, who had the audacity of desiring to be clothed and fed. At various points he calls this influence—his children—“oppressive and often malevolent,” “heavy,” and “baleful.” “Nothing […] could possibly be as important to me, could make as much difference,” Carver writes, “as the fact that I had two children. And that I would always have them and always find myself in this position of unrelieved responsibility and permanent distraction.” But he doesn’t end there: “I understood writers to be people who didn’t spend their Saturdays at the Laundromat and every waking hour subject to the needs and caprices of their children.”

In an incident central to “Fires,” Carver describes himself in a Laundromat in Iowa City, struggling to find a free dryer for his clothes. The episode is recalled with such specificity, with as much eye for detail as the latter half of “Cathedral,” that it belies the author’s earlier claim that he has a poor eye for details. You start to wonder if Carver merely has a selective memory. The clipped, closed-off, self-pitying voice in “Fires” comes to resemble the narrator’s voice in “Cathedral.”

The first time I read “Fires,” I imagined how I would feel if one of my parents had written it; I imagined the weight of responsibility I would feel for fucking up my father’s life, preventing him from doing what he loved most, keeping him from writing his novel (one of the criticisms most often leveled at Carver, which must have weighed on him during the writing of “Fires”). How might I feel about my childhood if my father said he would rather “take poison before [he’d] go through that time again”? I shook my head when I finished. What an asshole, I thought, dismissively.

After I had kids, my thoughts would return sometimes to “Fires.” The essay wasn’t quite so easy for me, as a father, to brush aside. Maybe Carver was simply expressing the sentiments of many writers who struggle to make time for their work. Maybe he was simply being more honest than the rest of us. Maybe I needed to come to terms with my own situation, because it was true in a sense that my kids were the reason I worked at a job I sometimes hated (we needed the health insurance). They were the reason I often wrote early in the morning or over my lunch hour: because evenings were reserved for laundry and picking up, helping with homework, dinner, and the bedtime routine. This was the real reason I’d become one of those writers, foraging for scraps of writing time. Yes, it frustrates me when I’m trying to write and my kids are running around the house screaming and fighting, shattering my concentration, interrupting me to ask for a snack or a new Ipod game.

But what Carver fails to acknowledge in “Fires” is that getting married and having kids are choices he made. He lets on as though he woke up one day in that Laundromat in Iowa City with this terrible obligation, as though it had been thrust on him. That, to me, is the ninety percent of the essay that remains underwater: the lack of personal agency. Carver got married early, he had kids early, and youth can be used to explain away some bad decisions, but they are decisions nevertheless. Kids can’t be blamed for being hungry or for wanting stuff. What kind of baggage is that to hang on your child? I don’t know the nature of Carver’s relationship with his kids, but I can’t imagine them being anything other than deeply hurt by his comments in “Fires.”

Carol Sklenicka, in her biography of Carver, briefly touches on the point. Carver’s son, Vance, as quoted by Sklenicka, tried to defend his father, claiming Carver “loved his family dearly,” but “when stress levels boiled over, he could despise us, find us burdensome.” Carver’s daughter, Chris, said that people she knew read the essay and formed unfair impressions of her. Carver wrote “Fires” when his children were twenty-three and twenty-four and no longer lived at home. Why was his resentment of them still so fresh in his mind at that point? Carver wrote the essay at Yaddo, where he had the solitude and uninterrupted time he needed to work on a novel; why was he squandering his time on a nonfiction screed about his children?

Why even bother writing an essay about influences when your sole point is to air some grievance about your kids? That seems a little too personal for an essay of this sort. While Carver does append a few comments about John Gardner and Gordon Lish, they seem cursory, tacked on, maybe even disingenuous given Carver’s sometimes fraught relationship with Lish. And if Carver was truly setting out to describe the factors that shaped his writing, why is alcohol never mentioned in “Fires”? In an essay on influences, there’s no reference to being under the influence. Drinking figured prominently in Carver’s life and is pervasive in his writing. How could it be more shameful to admit to an illness like alcoholism than to describe in print your dislike for your own children? Carver was a great writer, but still it takes a great deal of hubris to believe that the writing of stories, made-up tales, ink on paper, takes precedence over the children one has brought into the world.

My own two kids are young enough that I can still see them being formed. My inattention weighs as heavily on them as the moments I stop what I’m doing to play Barbies or Crazy Eights or backyard soccer with them. I’m not one who believes that everything happens for a reason. That’s just an easy way of shrugging off bad decisions. I believe in regret; I fear it. If it’s a choice between the moments I spend with my kids and the stories or poems I write, I choose my kids. No one will be hurt if I write fewer stories. My wife and a few others might even be spared the burden of reading them. But if I wake up to a quiet house after the kids have gone off to college, jobs, their own lives, and I have no good memories to fill the vacancy, that will be regret.