Although I repeatedly forget names and faces, I remember in crazed detail the interiors of houses I entered before losing my baby teeth. The slant of light, natural or artificial. The furniture. The furniture arrangements. Whether or not one couch cushion (more compressed than the others) showed evidence of a favored seat. Lamp globes and ashtrays, chipped or whole. Framed or unframed wall prints. Scatter rugs perfectly or imperfectly aligned with doorsills. Floorboard patinas. Even now, I’m a more reliable reporter of, say, the direction a chair faced in a room than the conversation that took place in and around that chair.

Although I repeatedly forget names and faces, I remember in crazed detail the interiors of houses I entered before losing my baby teeth. The slant of light, natural or artificial. The furniture. The furniture arrangements. Whether or not one couch cushion (more compressed than the others) showed evidence of a favored seat. Lamp globes and ashtrays, chipped or whole. Framed or unframed wall prints. Scatter rugs perfectly or imperfectly aligned with doorsills. Floorboard patinas. Even now, I’m a more reliable reporter of, say, the direction a chair faced in a room than the conversation that took place in and around that chair.

Given all that, I probably shouldn’t be surprised that what I remember most about my novels after they’re done are my characters’ homes or temporary lodgings—what’s in them as well as what’s not. Kitty Duncan’s breadcrumb-y bedroom in The Invented Life of Kitty Duncan, for instance. Thomas Senestre’s light-starved apartment in Senestre on Vacation, for another.

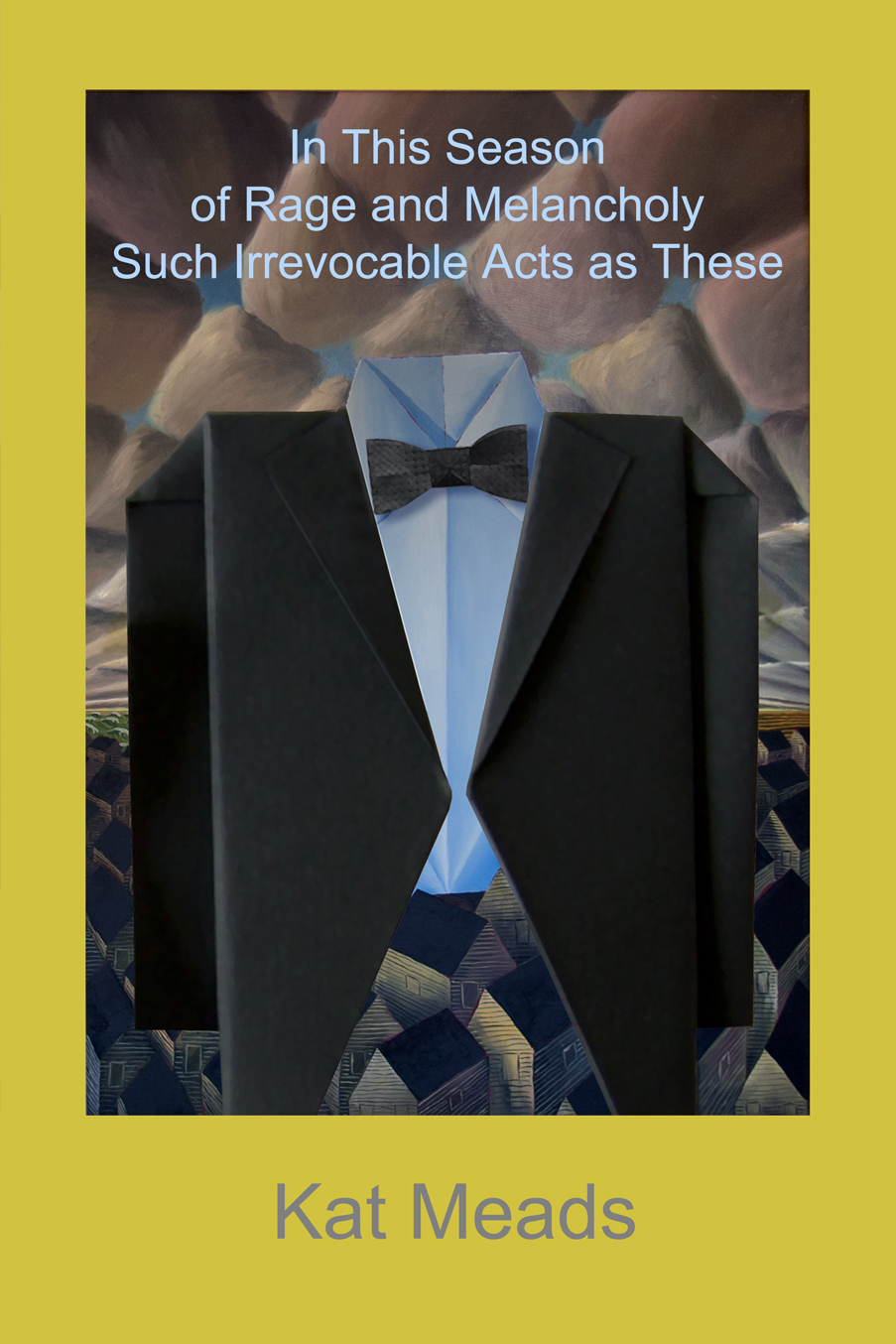

But there’s been a bit of an expansion in my “dwellings fixation” with regard to my most recent novel, In This Season of Rage and Melancholy Such Irrevocable Acts as These. This go-around I seem to have fixated on three:

1) The dilapidated “Cracker” house of Mickey Waterman’s childhood that he visits daily for incentive.

2) The Scaff farmhouse that George Scaff loves and his wife, Leeta, loathes.

3) The trailer in the middle of a cornfield that Beth Anderson initially associates with the joys of motherhood but that becomes, after her miscarriage, a reminder of failure and the setting for visits from an accusatory, tuxedo-wearing god.

In proofing the novel for publication, I returned to the manuscript some months after my last revision. Theoretically (at least), the break might have changed my perspective, diminished the importance of those two houses and house trailer. Didn’t happen. Instead those dwellings took on even more importance, so dominating the text they almost, almost assumed the status of characters.

Or so it seemed to me.

My interpretation only?

Would any other reader feel the same?

I do know that I was never unaware of those three residences and the interlock of their compass points during the writing. Even when Mickey and George and Leeta and Beth were physically elsewhere—playing softball in another county, drag racing, earning a living at their various job sites—the contents and spatial set-ups of their lairs felt omnipresent to me, narratively insistent. I also dreamed incessantly about those spaces—my nighttime working out, I suppose, of what should/shouldn’t happen in or around those homes to satisfy plot. The book is finished, out in the world, published in August by Oklahoma’s Mongrel Empire Press. And yet I still dream about Mickey’s “Cracker” house, the Scaff farmhouse and Beth’s cornfield trailer.

Will I always?

Very likely.