Then, I wanted to know what it was like to be nowhere. I had always lived somewhere before, rooted to cities by work, school, friends, family, and relationships. I wanted to be adrift.

I moved to Ohio to begin a doctoral program in English. I wanted to lose myself in the unfamiliar familiarity of books and find freedom in whatever that could mean. That fall in Ohio found me jumping through countless bureaucratic and administrative hoops, which would be a key component of my time there. I resisted and resented the impositions. My non-obedience opened up a class-shaped hole in my schedule; it was too late for me to fill it with another course. I resolved to cram it with books. On a whim, I began Book One of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s series, My Struggle, which had only recently been translated into English.

In the first pages of that first book, read during my first semester of study, young Karl, age eight, watches the news on TV. He watches a segment about a fishing boat that has sunk: I stare at the surface of the sea…and suddenly the outline of a face emerges. I don’t know how long it stays there…The moment the face disappears I get up to find someone I can tell. The boy seeks verification of his experience: proof, and the communion that’ll follow. His family refuses to satisfy his need; they don’t entertain his vision, which is akin to seeing a face in the clouds or the man on the moon.

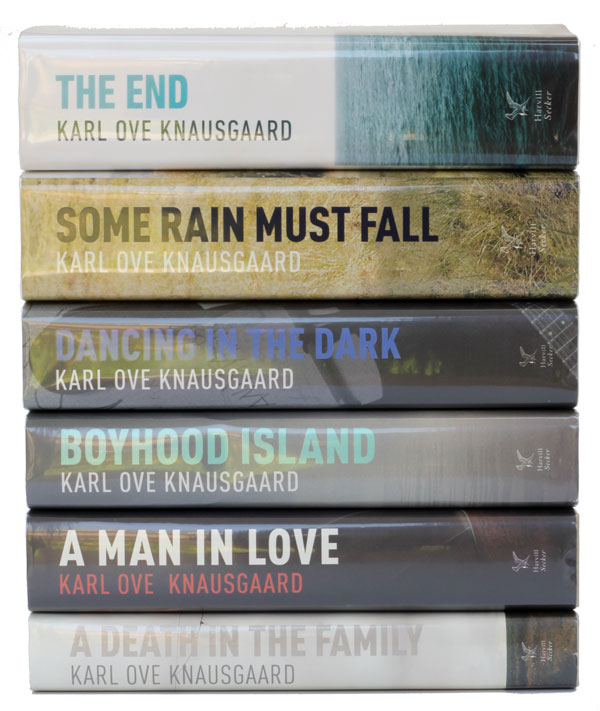

But of course the face existed. He saw it. I just wanted to find out if they could see what I had seen. To write is to confirm our sight, while forcing others to look to us—at us—even as we stay hidden beneath the water. As I sit at my desk writing, the waves swallow what once formed on the surface; the afterimage remains, along with the impression it made. Knausgaard wrote five more books to go along with the first. All of them are of a piece. They are, according to him, one novel. Following their publication, everyone looked at him, to him.

I moved to a rural university town in Ohio without ever seeing it. When I arrived, it certainly felt like nowhere, but I felt compelled, drawn to the place by that exact quality. Was it an act of faith, or the result of a lack for it? I didn’t need to tour rentals to figure out which to choose—I didn’t care about any of that. I didn’t need to see the place I would live. I wanted to not want anything. I didn’t succeed.

Almost four years have passed since then. I finished reading Book Six of My Struggle on the balcony of my apartment overseas, thousands of miles from where I began the first. It took me these years to read all 3,600 pages of the novel.

When I was sixteen, I thought life was without end, the number of people in it inexhaustible…The people who had been there then would become even more important, infinitely significant in as much as they had not only been shaping my perception of who I was, had not only been the people through which my own face emerged and became visible, but embodied the very understanding of how this particular life turned out the way it did.

This is from early in Book Six, in which the author tries to close the loop around the years of his life depicted in the pages of the novel. In the last book, he writes about the wild success of the first in the series. The response of readers, of the public, feeds into his writing.

Youth hides the lines that are manifest in the face, revealing the life that’s been lived: success, failure, and criticism are all parts of it. People intimately and vaguely involved in that life are part of it too. Perhaps the slow revelation of the face, its emergence, is more acute for the writer. I see what Knausgaard saw: the face and its lines. The other result is the novel, and words, which unlock time, heaving us outside it. That’s why we read, and why I write.

Abrade—yes. That’s the word. That’s what time does. We try to tie a bow and close the loop around time, our lives, but the text frays and unwinds it.

I recently began to experience tinnitus. For me, it’s a distant high-pitched ringing in my ears. For others, the sound is different, like a roar or drone. My experience is the literal effect of time; the aftermath of the life I’ve lived. I only notice it in the morning or evening, when it’s most quiet. I can hear it now, and I can pinpoint some of the concerts that damaged my hearing, all those years ago. The noise from then is still with me. No one else can hear it.

A note from SR: before you go, check out Derek’s contribution to Issue 22.