1. “Young Goodman Brown” by Nathaniel Hawthorne

A young man in colonial Salem, Massachusetts leaves his house, kisses goodbye his young wife, and heads into the dark and menacing woods to make a mysterious appointment. Along the way, he is briefly kept company by a conservative and neighborly man who, it turns out, is Satan.

The young man (Young Goodman Brown) protests that the meeting to which they’re both headed would be seen as an abomination by his father and grandfather; on the contrary: Satan informs Brown that he, the Prince of Darkness himself, “brought your father a pitch-pine knot, kindled at my own hearth, to set fire to an Indian village” and “helped your grandfather, the constable, when he lashed the Quaker woman so smartly through the streets of Salem[.]”

Disheartened, Brown falls away from the path, and while lingering in the woods, he observes a procession of Salem’s moral majority–the woman who taught him his catechism, the town minister, the deacon: all on their way to this same strange meeting, the one Brown dreaded, but felt he could not avoid.

He arrives at the meeting and is stunned to find his own sweet wife (Faith) there too. Everyone is there–the good and the bad of Salem:

“[H]e recognized a score of the church members of Salem village famous for their especial sanctity. Good old Deacon Gookin had arrived, and waited at the skirts of that venerable saint, his revered pastor. But, irreverently consorting with these grave, reputable, and pious people, these elders of the church, these chaste dames and dewy virgins, there were men of dissolute lives and women of spotted fame, wretches given over to all mean and filthy vice, and suspected even of horrid crimes.

Turns out that all of them, the high and the low, the prim and the skanky, have gathered here in the woods to celebrate the reception of new “converts” into the church of Satan. There’s an uncurtaining being committed here, a drawing aside of the drapes. The mystery into which young Goodman Brown and Faith his wife are being inducted is not the Christian one of faith and redemption through grace. Instead, Satan describes a communion of hypocrisy.

This night it shall be granted you to know their secret deeds: how hoary-bearded elders of the church have whispered wanton words to the young maids of their households; how many a woman, eager for widows’ weeds, has given her husband a drink at bedtime and let him sleep his last sleep in her bosom; how beardless youths have made haste to inherit their fathers’ wealth; and how fair damsels–blush not, sweet ones–have dug little graves in the garden, and bidden me, the sole guest to an infant’s funeral.

Satan describes a church organized not around virtue, but around sympathy and honesty. His new converts “shall exult to behold the whole earth one stain of guilt, one mighty blood spot.” He calls Brown and Faith forward–they’ve been married for three months, their matrimony ordained in the church of God, but now they stand in front of a different altar, and the homily is much altered. “Depending on one another’s hearts, ye had still hoped that virtue were not all a dream,” Satan says. “Now are ye undeceived. Evil is the nature of mankind. Evil must be your only happiness. Welcome again, my children, to the communion of your race.”

Brown and Faith move forward, toward a basin filled with–“water, reddened by the lurid light? or was it blood? or, perchance, a liquid flame?” And just before the Devil can complete this anointment, this counterbaptism, Brown looks at Faith, and Faith looks at him.

“Faith! Faith!” Brown cries. “Look up to heaven, and resist the wicked one!”

Brown never learns what happens next. He suddenly finds himself “amid calm light and solitude.” One might think he’s saved himself, and his soul, at the last possible minute. He walks out of the woods the next morning, and we’re allowed to believe that maybe the whole night was a dream. (But then what was he doing in the woods?)

The old minister is taking a walk before church and blesses young Goodman Brown. The deacon is praying through an open window. The woman who taught Brown his catechism is catechizing a little girl “who had brought her a pint of morning’s milk.”

He sees Faith. She is overjoyed at the sight of him, and skips down the street to plant a kiss on her husband, in sight of the whole town. “But Goodman Brown looked sternly and sadly into her face, and passed on without a greeting.”

Brown is never happy again after that night. He has looked upon the mysteries but refused to take the Devil’s offered comfort. He hears “an anthem of sin” inside each holy psalm. He imagines the roof caving in every time the minister preaches. He scowls and mutters whenever Faith and his children gather to pray.

After his death, “they carved no hopeful verse upon his tombstone, for his dying hour was gloom.”

2. No Way Out

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “Young Goodman Brown” had a strong effect on me when I read it my senior year of college. It was a study group assignment, and in the seminar afterward, I asked a troubled and sincere and probably kind of dumb question: “Is this story . . . immoral?”

What I meant was that I could find nothing firm inside the world of “Young Goodman Brown,” no conviction, no ground on which I could stand. Brown refuses the Devil’s offer, but still he dies unhappy. Why? Why? The story’s mood jibes with all the best intuitions of moral correctness: evil is characterized as evil, good as good. The hero, in his moment of crisis, makes the right decision. But his life forever afterward looks like a punishment. He is damned for resisting damnation. “Young Goodman Brown” is not like a Flannery O’Connor story, where one can always sense a future redemption rippling underneath the present venalities. If O’Connor had written “Young Goodman Brown,” then the finger of God would have reached out through that Black Mass in the woods and flicked the hero in the direction of grace.

There’s nothing like that at all here. The story might work as an indictment of Hawthorne’s culture, both on the charge of hypocrisy (those “hoary-bearded” churchmen and their maids) and also on the charge of political inhumanity (the genocide of the Indians, the intolerance of the Quakers). So maybe Hawthorne is trying to show a continuum of immorality between what is actually vicious but not publicly acknowledged as such (like the inhumanities of Puritan Massachusetts) and those secret, smaller, but recognized and officially approbated vices, of lechery, murderous greed, and post-term abortion?

Maybe. But isn’t there something righteous in the Devil’s argument that everyone should just be open and transparent about all this? Still, then, bizarrely, the Devil and his congregants are only willing to be honest about this fact in secret. But then it’s a secret they all share? Who are they hiding it from? Reading between the lines, it looks like the difference is age and marital status: Brown and Faith are only called as converts once they’re old enough to wed. I guess this is a secret that must be kept from children and the young? Why? Why preserve innocence only to corrupt it?

If the Devil is right, then maybe Brown’s gloomy death is the result of his own failure to “grow up,” to accept the hideous compromise between virtue and vice that allows Puritanism and colonialism to flourish. But if the Devil is wrong–which, I mean, you’d kind of assume would have to be the case? He is the Devil–then where is Brown’s salvation? Why is everybody back in Salem happy but him?

There’s an irony here that’s too subtle for me, at least, to understand. It reminds me of Huck Finn’s “All right, then, I’ll go to hell” or Tim O’Brien’s “I was a coward. I went to the war.” But I can only half-grasp that connection. I’m not able to see the paradox that gives the irony its sense.

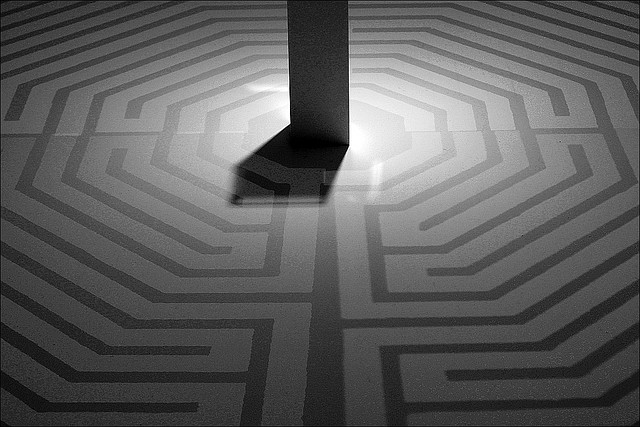

“Young Goodman Brown” is a labyrinth, but I can’t trap the monster, and I can’t save the princess, and I can’t find the way out.

3. True Detective and Serial

2014 began with one pop-culture freakout, and it’s ending with another: in the early months, we were all obsessed with True Detective; now, we’re all obsessed with Serial. It seems important to ask why this might be.

There are plenty of obvious differences between the two programs. One was a prestige drama on “paid” cable, the other is a free nonfiction podcast put out by public radio. The two could not be more different in tone: True Detective was grim and gothic, while Serial possesses a lightness of touch, almost a cheerfulness, in spite of its dark material.

Perhaps the most strikingly oppositional difference lies in the way these two stories address the question of personality. At the heart of True Detective lay an argument against the very concept of human identity. In his monologues, Rust Cohle cross-examined the belief that a person is anything but a self-deluded puppet–that is, a puppet who is deluded to think itself a self, coherent and free-willed, rather than simply so much horny gristle, a marionette carved out of water and blood and skin, with strings made of neurochemicals and old Chuck Darwin working the paddle.

On the other hand there’s Serial, which has this animating theory personified by Sarah Koenig’s earnest-to-the-point-of-pollyanaish faith in the idea that personalities matter–that a person’s behavior, their manners and forms of address, the way they carry themselves, the impressions other people take of them, the jibs they cut–that these are not appearances merely, but rather tokens of the true being beneath. The plot of Serial is driven by a binary set of mutually exclusive possibilities: Is Adnan telling the truth about his innocence, or is Jay telling the truth about Adnan’s guilt? The problem Koenig and her listeners keep bumping into is that both these guys seem like good, normal, non-psychopathic, non-pathologically-lying human beings. Koenig uses the word “nice” to describe Adnan, “sweet” to describe Jay–fully knowing that one of these guys might be a murderer, while the other is an admitted murder-accomplice. Whereas True Detective argued that a pre-human, amoral darkness resides inside everyone, Serial trusts that a semblance of love and decency and fellow-feeling isn’t merely a mask–it’s a clue.

That’s a little of what separates True Detective and Serial, but let’s look at what they have in common. There’s the young dead woman; the separation in time between the pivotal events and the present-day investigation–and then there’s something else, something that’s harder to articulate. It’s the way each of these shows contains an assortment of stray facts or images, seemingly disconnected from the main thread, but thrumming with moody significance. I’m thinking of the Neighbor Boy in Serial, and the gang-rape tableau of Barbie figures in True Detective. Each of these programs is a mystery, but mystery is more than a question without an answer. It’s a mood.

Then, underneath these shared characteristics, there’s something more essential to each program, something that I think accounts for their success, and it’s the labyrinthine nature of these stories.

4. The Dancing Floor

The labyrinth is a touchstone of human culture, both historically and developmentally. One finds labyrinths all over literature and history going back to the Greek myths; and before a child starts reading, her brain finds exercise by working a penciltip through a maze.

The writer nearest to us in time who best understood the importance of the labyrinth to human art was the late Guy Davenport. Here he is, in an essay on James Joyce called “Ariadne’s Dancing Floor” (you’ll find it in Every Force Evolves A Form):

The archaic Greek mind ascribed all things cunningly wrought, whether a belt with a busy design, the rigging of a ship, or an extensive palace, to the art of the craftsman Daedalus, whose name first appears in the Iliad. Homer, describing the shield Hephaistos makes for Akhilleus, says that the dancing floor depicted on it was as elaborate as that which Daedalus designed for Ariadne in Crete. This dancing floor is perhaps what Homer understood the Labyrinth to be. Joyce did, for the ground on which he places all his figures is clearly meant to be a labyrinth. Such floors, usually in mosaic, persist through history, spread by Graeco-Roman culture, and can be found in cathedrals (Bayeux and Chartres, for example), villas, city plans, squares, and formal gardens. They all display an interlacing of lines in a pattern that doubles back on itself in a “commodus vicus of recirculation” as a cicerone’s voice says in the opening paragraph of Finnegans Wake, which is a small model of a labyrinth containing other Joycean images of the kind of mazes he will elaborate on (and has elaborated on in all his previous books): rivers, time as shaped by history and myth, and choice environs (a word that derives from the Latin for the twistings and turnings of streets in a city). (my emphases).

There’s a tiny history of the world contained in those lines; I could stare at them and stare at them and never quite exhaust all their meaning. But one thing I’ve learned, from reading Davenport’s essays (the ones in EFEAF, and in the larger collection, The Geography of the Imagination), is that the labyrinth is both a puzzle and a solution to puzzles. Look up, at Davenport’s definition of the labyrinth, as “an interlacing of lines in a pattern that doubles back on itself[.]”

Find the labyrinth–find the materials that make up the lines, find the pattern, find the point where that pattern doubles back–and you’ll have gone a long way toward understanding what you’re looking at. Here’s are three cases in point:

5. Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining: Time as Shaped by History and Myth

A literal labyrinth would be really boring as an actual plot: following some guy past high walls, down dead-ends, into the center and out. No one wants that.

Yet literal labyrinths appear all the time in works of narrative art, and can usually be taken as a clue that a subtler labyrinth is at work somewhere.

Take Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, where a literal labyrinth stands right outside the Overlook’s front door–the hedge maze. Remember that moment, where Wendy and Danny are playing in it, while Jack is procrastinating from his play? Jack comes across a model of that hedge maze, and there’s this disorienting moment, where we think we’re still inside Jack’s POV, but actually, we’re looking down from a God’s-eye-view on Wendy and Danny. We see them moving around in the maze, like insects.

Let’s wonder about that, though. Maybe we’re not meant to move entirely away from Jack’s perspective. If Jack sees his wife and son as figures inside the maze, what does that mean to Jack, as a man, and with a man’s consciousness (shaped, like everyone’s consciousness, by history and myth)? What would Jack see if he saw his wife and his son inside that maze? What would that mean to him, since the mythological meaning of the labyrinth is a place where monsters must be faced, and killed?

One of the more terrifying symptoms of alcoholism is the way it can take people whom the addict would otherwise love and transform them, in the sight of the addict, into villains. Maybe that’s what’s happening when Jack looks down at the maze. In Jack, the Overlook has found a man whose craving for alcohol is a weapon that can be turned on the people he loves. Because here’s a man who would, on some basement level, willingly surrender to any theory that re-configured his family as the bad guys in his life. He quit drinking for them. But if they’re the villains, why does he need to stay away from the bottle? That’s the pattern of Jack’s alcoholism: seeing the bottle, not as a murderer, but as a savior; and seeing one’s family, not as loved ones trying to help you, but as monsters trying to take away the one thing that makes you happy.

If seeing Wendy and Jack as monsters in the maze is a literal rendition of the labyrinth, then the figurative walls down which Jack passes, the dead-ends in which he gets stuck, take their shape from the patterns of alcoholic rage, fused with and emboldened by the entitlements of patriarchal authority. Jack berates Wendy for not getting it–not getting that he’s signed a contract. He abuses her for distracting him from his “work.” His guilt over Danny’s broken arm–first repressed, then sublimated–is excused by the harm Danny innocently dealt to Jack’s play. Jack is drawn into the labyrinth by these arguments, these justifications for his own growing monstrosity. He joins the side of the real monsters, the ghosts inhabiting the Overlook, by re-casting his wife and little boy as the true bad guys of the play. He becomes trapped in a maze of aggression, self-pity, and hopelessness. He drank because of his own pain; he quit drinking because of the pain he caused Danny; quitting caused the pain of recovery–and then, when Danny gets hurt in Room 237 and Wendy accuses him of causing their son’s injuries, the pattern doubles back on itself, and Jack goes straight for the bottle, forgetting (on purpose) that the bottle is exactly where all of this started.

Almost immediately, this personal, psychological labyrinth fuses with the greater, supernatural labyrinth inhabiting the hotel. This supernatural labyrinth is built out of a strange combination of memory loss, ghosts, and time travel. Jack meets a waiter who’s supposed to be dead and doesn’t remember that he killed his family–but Jack does. Jack (who’s also supposed to be dead, or at least very old, considering the movie’s final image) doesn’t remember that he’s “always been the caretaker”–but the waiter does. Each man remembers the other, forgetting himself.

And here the pattern of time as shaped by history and myth doubles back. The needs of Jack’s alcoholism, and his own sense of male entitlement, fuse with the pattern of the Hotel’s hauntedness. Jack doesn’t see the Hotel as a murderous force, but as a thing to be saved (like his own craving for a drink); and Jack doesn’t see the Hotel as a threat to his family, he sees his family as a threat to the Hotel. His contract gives him a mandate to eliminate these threats, and so he re-configures his wife and son’s good intentions into a labyrinth in which he must avoid becoming trapped (he doesn’t avoid this, at first; he gets dead-ended in the freezer). Meanwhile, the labyrinth he’s trying to escape is the one where his family isn’t murdered, where the history of the Hotel (Ullman’s chopped up wife and girls) isn’t re-created. By seeking escape from this labyrinth, he draws his family inside the other one. Delusionally, he perceives himself as Theseus, his family as the Minotaur, and the Hotel as an Ariadne to be saved.

Return to that moment of disorientation, where we think, for an instant, that we’re inside Jack’s head, but really we’re looking down on Wendy and Danny in the maze–but really, we are, in fact, inside Jack’s head.

6. Christopher Nolan’s Inception: Choice Environs

Mazes, maze-making, and the myth of the labyrinth are all over Inception (one of the characters is named Ariadne). But the function of the labyrinth deployed by the characters to pull off this heist is the same as the one deployed by Nolan, and it’s what every serious artist tries to offer the audience: catharsis. The manufactured cityscapes, landscapes, and interiors are used by Inception‘s characters to draw their mark into an emotional labyrinth, which takes its shape from the complexities of the bond he has with his father.

Notice here how something as mundanely, even generically fraught as a father-son relationship can look like a labyrinth. A father loves his son, a son loves his father. The son is infantilely uncomplicated and reaches for the father’s love. The father has been hardened by the strictures of masculinity and fails to requite this love, however much he might want to. This transforms the son into a man like his father and the first pattern of the labyrinth is complete: the simple, straight-line path of father-son love has been twisted around and disrupted by the interference of an outside code. Now the son is grown, he is hardened, and the father, weakening in middle age, or softening as approaching death triggers a reevaluation of priorities, reaches out for his son’s love. The son doesn’t give it. He can’t. The labyrinth has doubled back on itself.

I mean, this is like 98% of all father-son relationships, isn’t it? Some form of this drama seems to play out almost uniformly across the entire father-and-son portion of the human race. In this particular iteration I’ve given, the labyrinth is a metaphor for a certain kind of relationship, but it also illuminates the labyrinth’s broader strategy, in every iteration. The labyrinth takes what should otherwise be a simple transaction and confounds the human desires at the heart of it with an overlay of complexity, diverting what’s straighforward into twists and turns, dead-ends. Fathers and sons want to love each other; but masculinity confounds (and masculinity, as a code of manners, takes its content from the field of history and myth; so cf. The Shining).

The heist in Inception introduces another layer of complexity, by introducing the problem of capital wealth. Fischer, the mark, has a typically strained relationship with his father, but this is complicated even further by the insane amount of money at stake. And here, another interesting strategy of the labyrinth appears: only when people are trapped can they experience the release of escape. So the literal labyrinths into which the inceptors draw Fischer mirror the figurative labyrinths in which he’s lived all his life. The dreams reenforce his own anxieties and fears, they throw into relief the emotional pain he feels toward his father–all so he can be fooled into achieving a resolution.

The labyrinth doubles back on itself, but here, the labyrinth, in the hands of the inceptors, has pulled off a trick I can only describe as keyser-sozean: Fischer is trapped forever precisely because he is convinced he has escaped.

7. David Fincher’s Zodiac: Rivers

My dayjob is criminal defense, and one thing it shares with my work as a freelance nonfiction writer is this: you have to make do with the facts as they are.

It’s the same way with police work, and that’s why the particular species of labyrinth at work in Zodiac is like a river. A river twists and turns and winds around and runs on and on, but the pattern is readymade, prefabricated, prehuman. It’s a given.

The first pattern of Zodiac came to life long before the movie starts, and it’s the pattern of the murders themselves. Serial murder, unlike most murders, doesn’t begin with emotion–serial murders aren’t “crimes of passion”. Of course, not being a serial killer, and not being able to see inside the heads of serial killer, I could be wrong about this, but serial murder seems to begin with imagination. There’s an overlap between serial killing and art, which is both perverse, and perhaps also helps account for why serial killers make such fascinating subjects.

But already we’re running into problems, because of the ingenious way Zodiac is constructed. Zodiac plays like it’s beginning with the first murder, because after the killing, the newspapers and police departments receive the letters with the ciphers. But in fact, as we find out later, Zodiac has already killed. We also think this first killing we see, like most serial killings, is somewhat impersonal. In a non-serial murder, the motive is usually inherent to the victim: those killings are what we would call “personal”; but the motives of a serial killer aren’t personal, they’re artistic, proceeding from a superstructure of the killer’s own interests and desires and fascinations. The approach to catching a serial killer, then, is something like the approach to understanding a work of art. The cop becomes a critic of the killer.

Accordingly, the investigation prompted by this first killing involves a search for patterns: why does Zodiac kill near water? Why does he kill on lovers’ lanes? Why does he attack couples, kill the woman, but leave the man alive? But then right away, Zodiac breaks the pattern. He kills a random cab driver. And then, farther on in the movie, almost near the end, we learn that the first killing we saw (actually Zodiac’s second killing) wasn’t entirely impersonal. Zodiac knew the female victim.

With this kind of labyrinth, you’re never at the beginning. You’re always farther downstream. And the pattern which began in the killer’s head is expressed only imperfectly through the medium of his murders. This resembles artistic failure, of course, but the practical effect on the investigation is an inability to see how the facts make any sense. Things don’t fit together. And so you get two patterns–the idea behind the killings, contained in the killer’s mind, and the theory for what that idea might be, pieced together by the cops from the facts left in the wake of the killer’s actions.

The place where these patterns merge and form a labyrinth, and the point where the labyrinth doubles back on itself, is one and the same: human error. Human error prevents the killer from perfectly expressing the image in his head–which is lucky for him, because the more clearly he expresses that image, the easier it becomes for the cops to catch him, to “get inside his head” and crack his pattern and trace that pattern back to its source.

Human error compounds the problem, on the cops’ side. Information isn’t shared, leads aren’t followed up on. A false report that the cabdriver was killed by a black man causes two beat cops to completely ignore a large white guy lumbering away from the crime scene. Facts that we think have been fully established are overturned: at a crucial moment, the police handwriting expert excludes the cops’ best suspect; then later, that expert’s judgment is called into question. Everyone is simply carried along–the killer by his deadly impulses, the cops by their hobbled facts–like bodies caught up in a current.

Epilogue. 9/11 Was An Inside Job Pulled Off by the Wizard of Oz

Someone on the Internet–I wish I could remember who, so I could cite them–gave an interesting argument for why people are drawn to conspiracy theories, about the Illuminati, or the “false flag” operation that brought down the twin towers, or the LBJ-led cabal of Russians and gangsters and mafiosi and Cubans and Cuban refugees and spies and John Birchers who assassinated John Kennedy. Perhaps the reason people cling to these theories, the argument goes, is because they’re afraid that life really is as randomly chaotically terrifying as it seems. But if there’s a man behind the curtain, putting on the show, isn’t that easier on the psyche? If modern life is a labyrinth, doesn’t that mean there has to be a way out?

Perhaps that’s the reason we go so pop-culture gaga over works of art like the ones I’ve discussed here. We crave a vision of the world as a puzzle to be solved.