I was a senior in high school when the Notorious BIG died. Back then, during the height of the East Coast vs. West Coast Rivalry, hip-hop figures felt more like professional wrestlers than young men. They had “stage” names. They had entourages. They operated in a constant state of conflict. Their whole scene was so over the top, it ceased to be real for me. Now it’s 25 years later. I’m 42 years old. I teach English at an inner-city high school in Upstate New York. And I’m still trying to process Biggie’s violent death, to properly lament all that was lost on that tragic night in 1997.

A few days ago, I saw a Facebook post from a woman I grew up with. It read, “SiriusXM channel 105 is now Notorious BIG radio!!!” Without delay, I punched it up, and suddenly I was 17 again. It was Memorial Day Weekend, which meant everyone was at Lake George, a resort town sixty miles north of Albany, and “Mo Money, Mo Problems” blared from tricked-out cars and Jeeps with no doors that crawled down the crowded strip, Federal agents mad ‘cause I’m flagrant/tap my cell and the phone in the basement… Biggie had been dead just two months, and his posthumously-released double-album Life After Death ruled the radio waves. We had no idea who’d shot Biggie. But we understood it was revenge for Tupac Shakur’s slaying the previous November. And now that both kingpins were gone, America’s Rap War could end.

It might seem strange for a white boy from Upstate New York to feel any kind of connection with Biggie Smalls, whose birthplace of Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn is practically on another planet. But my life began much like his. I was born September 26th, 1979 at Albany Medical Center. My mother was just twenty years old when she had me. I never knew my real father. Me and mom started out with her parents in a part of North Albany that had once been dominated by an Irish-Catholic constituency. But, by the time I arrived, a racial shift was in full swing. I was the only white kid in my kindergarten class. Like Biggie, I suffered from strabismus, a medical condition in which the eyes don’t properly align. From this, I developed a crippling inferiority complex. I refused to have my picture taken. I wouldn’t make eye contact with people when they spoke to me, often giving the impression that I was hiding something, or lying about something. Then I heard Biggie say, Heartthrob–never/Black and ugly as ever, with all the confidence of a King. And that gave me confidence. That lyric became a mantra. It helped me stop hating myself. Instead of letting my unfortunate eye condition defeat me, I took steps to correct it.

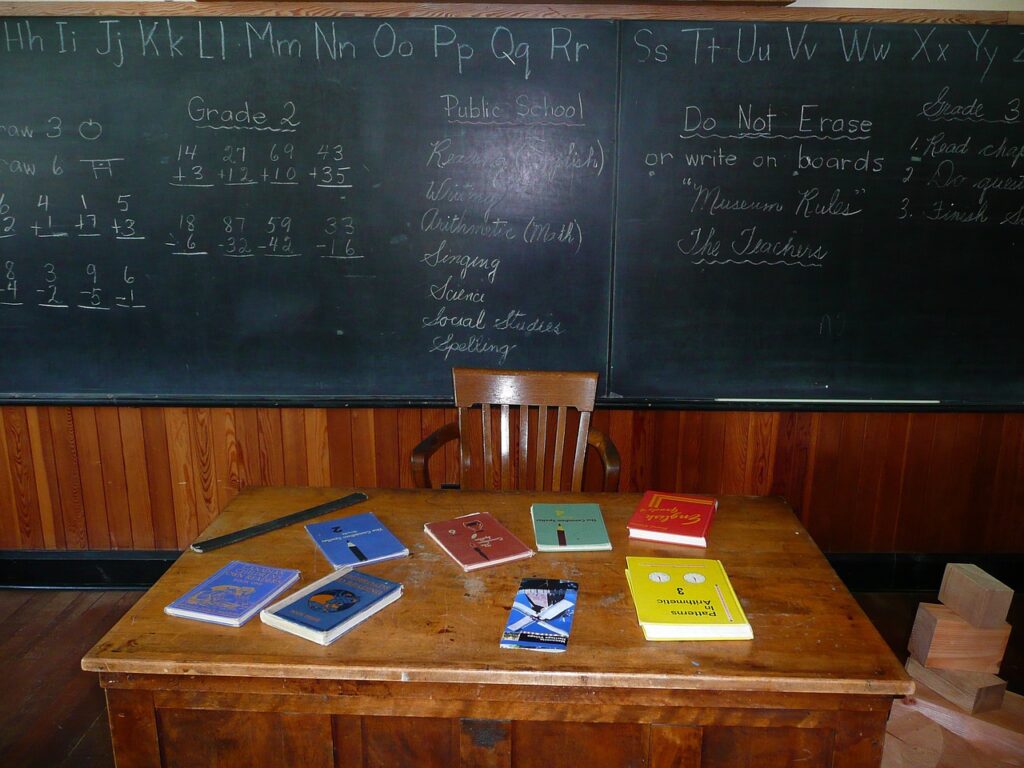

As a teacher, my first classroom was a converted storage area in the school’s basement level. The walls were paint-peeled and pockmarked. There was no window. No bookshelves. No books. I was assigned five sections of remedial English, the ones nobody else wanted to work with. My students were mostly black or Hispanic. They had discipline problems. They came from unthinkable living situations. The average literacy was at a second or third grade level. Before I could actually teach them anything English-related, I had to establish some sort of connection. I tried icebreaker games like “This or That” and “Desert Island.” Nothing worked. They saw me as just another white-guy teacher in their endless line of white-guy teachers. Then everything changed. One day, in early October, two boys at the back table began to loudly argue, and I wasn’t sure what I’d do if they got physical. At some point, one boy said to the other, “You want beef, bring it.” Without thinking, I began to rap, What’s Beef?/Beef is when you need two Gats to go to sleep/Beef is when your moms ain’t safe up in the streets…

“Yo, Huba, you know Big!?”

“Yeah, I know Big.”

I still work at that same school. My current classroom is on the top floor. Its windows overlook a courtyard that doubles as the Senior Lounge in warm weather. I’ve been here for sixteen years. In that time, I’ve taught all the most-recognizable writers, everyone from William Shakespeare to Stephen King, Maya Angelou to Ernest Hemingway, John Grisham to John Steinbeck, Harper Lee to JD Salinger. And I can tell you with total certainty that the Notorious BIG is a finer wordsmith than all of them. Don’t believe me? Google the lyrics to “Everyday Struggle,” then ask yourself: who can write this? Who can so masterfully manipulate the English language? I’ve poured over Biggie’s catalog for two decades and it still scrambles my brain. Every line, every lyric: stratospherically brilliant. As an educator, and a published writer, I wouldn’t have the first clue how to teach someone to do what Biggie could do. All before the age of 24! I can only come up with two conclusions. 1) He read everything under the sun, fully absorbed every word on every page, then instantly understood how to weaponize it. Or, 2) Biggie Smalls was a God.

Sometimes when I start class by saying, “Okay, guys, here’s today’s agenda–” I’ll silently sing to myself, …Got the suitcase up in the Sentra/Go to Room 112/Tell them Blanco sent ya…

The best hip-hop song of all time is Biggie’s aspirational anthem, “Juicy,” which begins with the line, Yeah, this album is dedicated to all the teachers that told me I’d never amount to nothin.’ This sentiment hits me hard. Presumably, if what Biggie says is true, there’s a teacher out there who once upon a time dismissed Christopher Wallace as a lost cause. I’ve made it my solemn vow to never be that teacher to any student. Public education isn’t a one-size-fits-all situation. Talent and potential come in countless forms, and it’s my job to detect it, then guide it, then help it grow. A teacher who couldn’t see that Christopher Wallace was the Notorious BIG…I cannot imagine a more-appalling indictment against our profession.

25 years later, and the murder of Biggie Smalls remains unsolved. Whoever fired that fatal bullet might still walk among us, knowing he got away with it. Biggie was just 24 when he passed. Today he’d be 50. In 2017, Biggie’s mother, Voletta Wallace, said, “He was so young, so talented, and his life was taken far too soon.”

While Tupac seemed to thrive on the idea of a bicoastal rap war, I truly believe Biggie didn’t want it. When Shakur died, Biggie’s estranged wife, Faith Evans, said, “I remember Big calling me and crying. I think it’s fair to say he was probably afraid, given everything that was going on at that time and all the hype that was put on this so-called beef that he didn’t really have in his heart against anyone. I’m sure for all he thought, he could be next.”

Don’t get me wrong: Biggie was a rough-and-tough guy. Biggie was a criminal. And he didn’t write Walt-Disney songs. Not even close. Yet, when I listened to his lyrics, I always sensed a soul-deep desire for the good life…back of the club/Sippin Moet is where you’ll find me…

When Biggie died, the usual slew of conspiracy theories made the rounds. It was staged. He’s still out there. Him and Tupac played us all. This sort of thinking was certainly helped along by the fact that the album released shortly after his passing was eerily-titled Life After Death (which followed the also-eerily-titled Ready to Die). The album’s cover showed Biggie in a long black coat leaning against a hearse. He wasn’t smiling. He wasn’t mad. It was what it was. But what sticks with me most about that album is a line in the song “Kick in the Door,” Your reign on top was short like leprechauns.

Looking back, such conspiracy theories were a way for us to cope. I recognize that now. The world’s greatest rapper was cut down in the prime of his life, and we lacked the sophistication to properly process all that was lost. But he was so much more than just a rapper. He was a son. A husband. A father. Or, as he would put it, My daughter use a potty so she’s older now/Educated street knowledge I’ma mold her now. Biggie didn’t deserve to die the way he did, when he did.

But maybe, just maybe, this tragic tale has a happy ending. Maybe our crazy conspiracies are actually true, or sort of true. Maybe Biggie Smalls is still out there living his best life after death. Maybe he’s lounging on a private beach in a parallel universe. Maybe that fatal bullet missed its mark on March 9th, 1997. Maybe there never was an East Coast vs West Coast Rap War. Maybe It was all a dream.

In one of my English classes, there’s a kid named Angel. He’s not a traditionally-good student. He frequently blows off assignments. He gets in trouble…a lot. But Angel has a dream. Angel wants to be a world-famous rapper, and he works nonstop at it. He’s always busy thumbing lines and lyrics into his iPhone. His “stage” name is “AngelFromNE.” He tells us to “Stream AngelFromNE on all platforms.” So, one day, I did just that. I streamed AngelFromNE, and listened to a few of his tracks. He’s very raw, but there’s potential there.

When I saw him again, I said, “Angel, you need to read everything you can get your hands on. All the great ones know words. They use words to tell their story. They find a way to make unrhyming words rhyme. You have to be able to manipulate the language.” Then I asked Angel, “You know about Biggie?”

“Not really,” he said. “Biggie’s before my time.”

“Okay,” I said. “There’s this song I think you should Google.”