If you studied poetry in high school, you may have not-so-fond memories of being asked to endlessly dissect Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken” or perhaps William Carlos Williams’s “The Red Wheelbarrow.” Maybe your teacher asked you to extract a poem’s rich symbolism, to explain its meaning, and maybe the consensus you came to was that all poems are really metaphors for Death or Love or Other Big Concepts. (I remember one particularly painful English class where someone drew a box around each stanza of Williams’s wheelbarrow poem and proclaimed that they were, in fact, shaped like wheelbarrows: symbolism of the highest order.)

Maybe, despite the occasionally asinine discussions, this sparked your enduring love for poetry. But did your English teacher ever talk about the importance of poetry? Did he or she ever stand there and reassure you that one day you’d be grateful you read Frost, the way your math teacher insisted that you’d one day thank her for teaching you algebra? It seems to me that the tendency to dismiss poetry as eccentric or irrelevant starts with the way we interact with it in school.

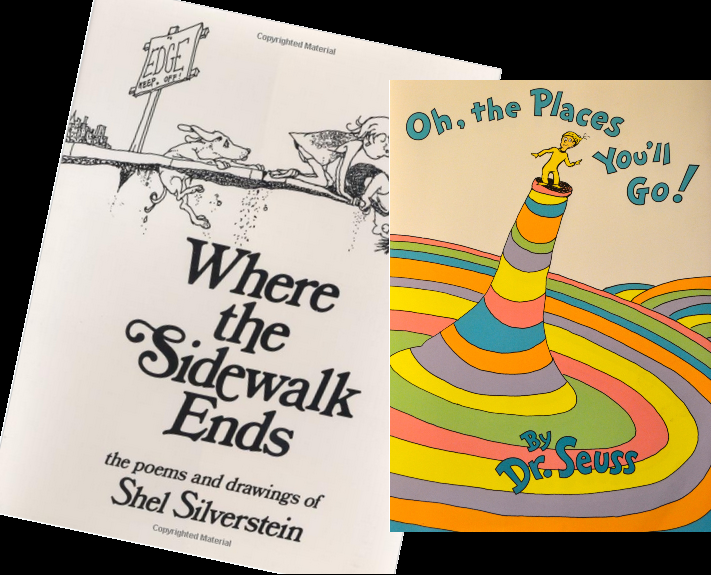

Of course, most of us encounter poetry long before we’re asked to study it. We grow up reading Shel Silverstein or Dr. Seuss or other rhyming books. We grow up learning chants at summer camp or rhyming our names in an endless loop (Casey, Casey, Bo-Basey, Banana-fana…) or just making up nonsense words to pass the time. We learn to talk and read by fumbling with language, by stretching it to its limit, which is the beginning of poetry. But by the time we get to school, poetry becomes just another topic on the agenda, a vehicle to teach students the definitions of diction and tone and mood.

Of course, most of us encounter poetry long before we’re asked to study it. We grow up reading Shel Silverstein or Dr. Seuss or other rhyming books. We grow up learning chants at summer camp or rhyming our names in an endless loop (Casey, Casey, Bo-Basey, Banana-fana…) or just making up nonsense words to pass the time. We learn to talk and read by fumbling with language, by stretching it to its limit, which is the beginning of poetry. But by the time we get to school, poetry becomes just another topic on the agenda, a vehicle to teach students the definitions of diction and tone and mood.

The way we talk about poetry affects how students will think about its value, and it’s too often discounted. After I taught a week-long poetry camp recently, I handed out an evaluation to the students, who were all around high-school age. Though all of the students said the class helped them improve their creative writing, only some of them said it would also help them be a better writer in school. Having seen firsthand how reading and writing poetry can improve students’ language skills, the disconnect between these two answers is frustrating. But I don’t blame the students; rather, it’s an example of the way poetry is presented in our schools and consistently undervalued in our culture. We don’t talk about it as a useful skill, when in fact it’s an incredibly useful tool to expand vocabulary and introduce students to many different voices and topics. (And for a perspective on the undervaluing of poetry in monetary terms, I recommend Jessica Piazza’s wonderful project and companion blog, Poetry Has Value).

Although teaching is not my profession, I’ve had the chance to teach creative writing to various populations over the last several years, including juvenile delinquents, elementary school students, and adult writers. Still, I don’t claim to be an expert. But the power of language and writing is so clear to me that I can’t help but wonder what would happen if we gave poetry a little more attention in the classroom, if we celebrated its ability to craft something beautiful and startling out of the same words we use every day. In my experience, teachers are often surprised by the ways poetry can be tied into other academic subjects. Plan a lesson on cinquain and students get practice with identifying words as nouns, adjectives, or verbs. Plan a lesson on haiku and students get practice counting syllables. Teach a lesson on William Carlos Williams’s “This Is Just To Say” and even third graders can identify the irony. So why don’t we value poetry in the same way we value multiplication tables or the timeline of the Revolutionary War?

Despite the fact that studies have shown many students are reading below grade level, particularly black and Hispanic students, as well as students from low-income backgrounds, teachers often skip over covering poetry completely, especially in the younger grades. It’s often the case that they don’t know enough about poetry to feel comfortable teaching it. (When I’ve visited classrooms to teach, that’s the most common thing I hear.) But it’s also a wider problem that stems from the culture of constant testing in our education system. If no one is demonstrating the value poetry can have for students, teachers are apt to see it as frivolous, especially when there are “important” (and testable) skills like math and science to cover.

True, poetry won’t get a man to the moon. But what good are the equations that get him there if he can’t communicate clearly what he’s seeing once he lands? Poetry can be as important as the five-paragraph essay to the way we teach students about language if we’d only let it. As Williams famously wrote, “It is difficult / to get the news from poems / yet men die miserably every day / for lack / of what is found there.”