As a nurse practitioner who has worked in Intensive Care, on the Oncology Ward, and in Women’s Health, I’ve never had to search for “ideas” for poems—observed moments of grief, the joys of healing, the mysteries of birth and death. As a proponent of the genre variously titled Literature and Medicine, or Medical Humanities, or Narrative Medicine, I’ve written about what it’s like to be a caregiver and I’ve written about my patients.

As a nurse practitioner who has worked in Intensive Care, on the Oncology Ward, and in Women’s Health, I’ve never had to search for “ideas” for poems—observed moments of grief, the joys of healing, the mysteries of birth and death. As a proponent of the genre variously titled Literature and Medicine, or Medical Humanities, or Narrative Medicine, I’ve written about what it’s like to be a caregiver and I’ve written about my patients.

For me, nursing and literature long ago merged: The mysteries of existence are revealed in writing that is grounded in the sensual reality of the human body.

I’ve believed that my poems about what I do as a nurse are authentic; they are written from my experience, from inside the moment. I’ve also hoped that my poems about patients are authentic—I share incredibly intimate moments with them. But lately I’ve been wondering: How successful can I be—can we be—when we write as if we know what someone else is experiencing? I’m not talking about persona poems, fictional characters, composite characters, or bits and pieces taken from our imaginations. I mean what happens when we write about someone else, a real someone else, as if we, for the space of the poem, are qualified to speak for them?

This “dual vision”—writing about our lives yet also claiming to know another’s—may be a problem particularly for nurses and doctors who write about their work; yet it’s something we all might consider. I’ll begin by sharing two poems, examples of my particular dual vision. In this first poem I write about my experience of being a caregiver; in the second, I speak as if I am the patient.

Examining the Abused Woman

Her face, when she turns, is like a peach

left in the refrigerator drawer too long,

nose and cheek caved in, as if underneath

the fleshy matrix has been chewed away.

When I ask past medical history, she lists

the broken bones:

Humerus, ulna, sternum, nose, jaw, twice,

eye socket, she points, here.

I palpate her face, dip my fingers

into the little valley of her clavicle, scared

to press too hard. I see her bare.

She breathes, I listen with a stethoscope,

her breath like wind drawn down a New York alleyway.

All the time we talk.

I memorize her puffy feet, her pubic hair,

the scars that rise like topographic maps

across her abdomen. Hand slicked

with lubricant, I probe to touch her ovaries,

hold her uterus between my open palms.

She says she lives in Westchester, a home of sorts.

I finish the exam. She dresses and, not looking up,

thanks me for being kind. How could I say

It’s no use to hate or I bless you with my fingertips?

It’s me who is afraid.

—from Leopold’s Maneuvers (University of Nebraska Press)

In “Examining the Abused Woman,” the reader sees through my eyes and shares my thoughts. Certainly we often write this way: first person, I was there, you can believe that this is accurate information about what happened! And I’ve found that readers often want to believe that when we write “I,” unless otherwise indicated, we are telling the truth, at least the metaphoric truth.

In the following poem, I am a patient, content in her illness, easing into a gentle death, even a welcomed one.

The Patient Speaks

I am in love

with my bed, my radio

and the gilly-flowers

wilting on the cold sill.

I love this room.

It is mine

my whole life.

The nurse knows

my name; my name

is on the door.

She knows I am ticklish

and like my feet soaked.

I am riding

the big wave.

I wait for my doctor;

he is not afraid

of my bony hand.

The flowers

are so quiet.

Like them

I will sleep,

my body deepening

into this

most beautiful bed

I’ve ever known—

my sheets, my love,

my pillow.

Although this patient is un-named, I assumed, observing her, that these were her correct emotions; I wrote of her calm in the face of impending death. But what if I was wrong?

Just as I was considering how and when a poet might be justified in taking liberties with interpreting another’s experience, and how and when the resulting poem might take on its own life, rendering a correct or incorrect interpretation meaningless, various tragedies began to devastate both the world and my own neighborhood. I have good friends in Newtown whose kids go to school in Sandy Hook, friends whose lives were forever changed. I watched as they struggled to heal. I witnessed how Newtown quickly developed a culture of its own, in a way similar to the unique culture that develops within an ICU or a cancer ward, where patients, like a town’s residents, suffer not only individually but also collectively. While many writers rushed to publish their interpretations of this tragedy, I realized that I, on the outside, couldn’t truly enter or understand the culture—the narrative—of Sandy Hook. Such understanding, I thought, might be possible only when one’s own town was suddenly struck with disaster.

And perhaps a nurse could not truly understand another’s illness narrative, could not authentically plumb another’s suffering for poems or essays, unless the nurse’s body suddenly fell prey to its own disaster.

In the summer of 2013, I was admitted for a routine, one-day surgery. Everything went wrong, and I was hospitalized for 26 days. No longer interpreting another’s illness, I stepped right into my own tragedy; the nurse became a patient, and I became my poems. Although I write about the world of illness and healing, who among us has not stepped into his or her own poems—into the narrative of divorce, war, depression, poverty, abuse, disability, the suffering of loved ones, disappointment, loss, indecision and fear?

At home, recovering, I could not write about my illness, which had been both life altering and life threatening. So this is what it’s like to be inside a patient’s narrative! So this is what it’s like to have those around you think that they correctly hear you and understand your words and actions! How clearly I saw that if the doctors and nurses who cared for me tried to write my story, they would get it wrong.

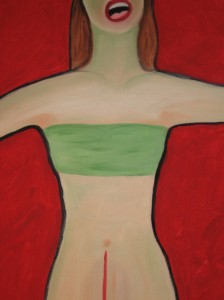

Although I couldn’t respond to my hospitalization in poems, I found comfort and release in painting. In a rush, I painted twelve “poems” on canvas, individual moments that called out for contemplation. Maybe someday I will write about those 26 days; maybe I will write about the other patients I met there. When I do, I will write with new caution, new respect for how, while I may know my own narrative, I can only intuit another’s. I might just show my poem to that patient and ask, did I get it right? Can you help me be a better poet?

The Second Painting: The Experience of Pain: “On a Scale of One to Ten”

Today we are pleased to feature author Elizabeth Naranjo as our Authors Talk series contributor. In her podcast, Elizabeth discusses “The Woman in Room 248” and reveals how some of Mary’s experiences are loosely based on her own nursing experiences. She also expands upon the characterizations of Mary and Shirley and shares how she can relate to both characters.

Today we are pleased to feature author Elizabeth Naranjo as our Authors Talk series contributor. In her podcast, Elizabeth discusses “The Woman in Room 248” and reveals how some of Mary’s experiences are loosely based on her own nursing experiences. She also expands upon the characterizations of Mary and Shirley and shares how she can relate to both characters.