Carolyn Guinzio is the author of seven collections. Her new collection A VERTIGO BOOK (The Word Works, 2021) was the 2020 winner of the Tenth Gate Prize. Her work has appeared in Poetry, The Nation, The New Yorker and many other journals. She lives in Fayetteville, AR. Visit her website to learn more.

Our Issue 28 Art Editor, Khanh Nguyen, wrote a few interview questions for Carolyn and this is her lovely response:

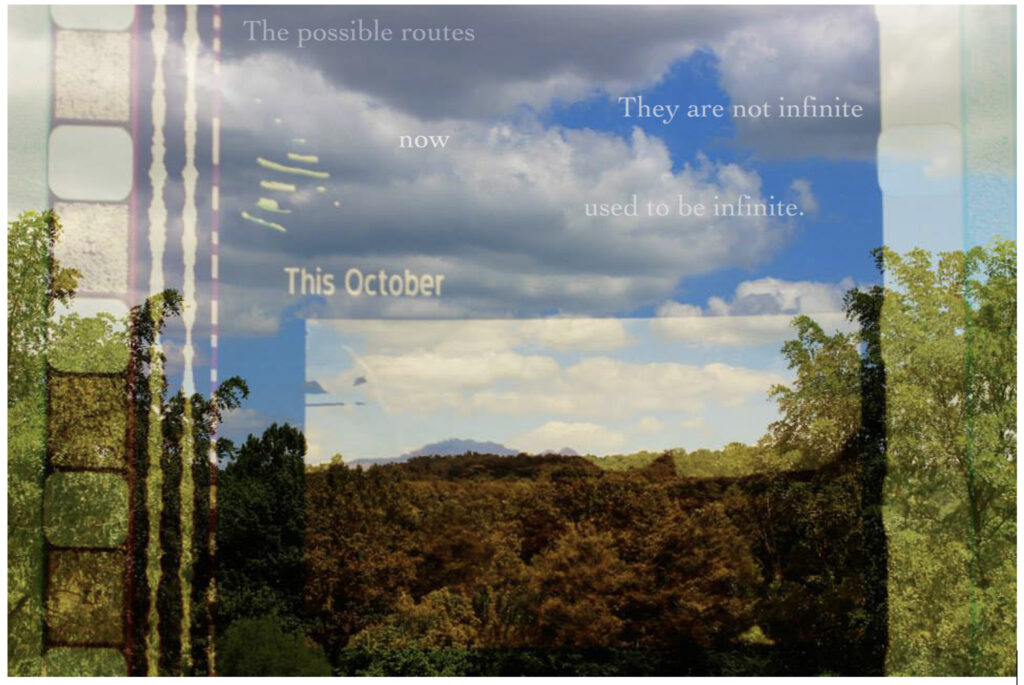

Carolyn Guinzio: I have found that I can reach places with visual poetry that I could not get to with text alone. It started somewhat accidentally, when I was with my son in a second hand store in Fayetteville, Arkansas, where we live and where he has grown up. Covered in dust in a corner we found a film reel. It was unwrapped, and it had no price on it. We held it to the light and realized it was a trailer for the movie Elizabethtown, which takes place and was shot in the town where my son was born. The strangeness of inexplicably finding it there was inspiring. We knew we could make something from it. I layered macro-photos of frames from the trailer over photographs of our current environs: our road, the hills, the windows of our house— and then layered micro-poems primarily about my son: his birth, his earliest years (we lived in Kentucky the first 18 months of his life). My hope was to get at something about time, memory, place, and loss. We lived on the eastern edge of the Central time zone, so we had to cross into Eastern time to get to the hospital: something I always found peculiar and a little disorienting. What time was my son born? How do places impact our sense of our own identities? Something about the layering of images with these ideas I felt helped me examine a complicated pursuit in a way that was more evocative and subtle than I was capable of through just text.

I was a total convert after that, particularly since place is so important to me in my work. The next thing I tried was about the experience of revisiting old haunts on Google Earth. There’s nothing like it to make one realize how limiting a virtual visit can be. I love these technologies, and having access to them is what makes so much of what I try to do possible, and yet, and yet— looking at an image of the street where I grew up does not feel like standing on the street where I grew up. A combination of media might get me closer to what fragments of memory actually feel like.

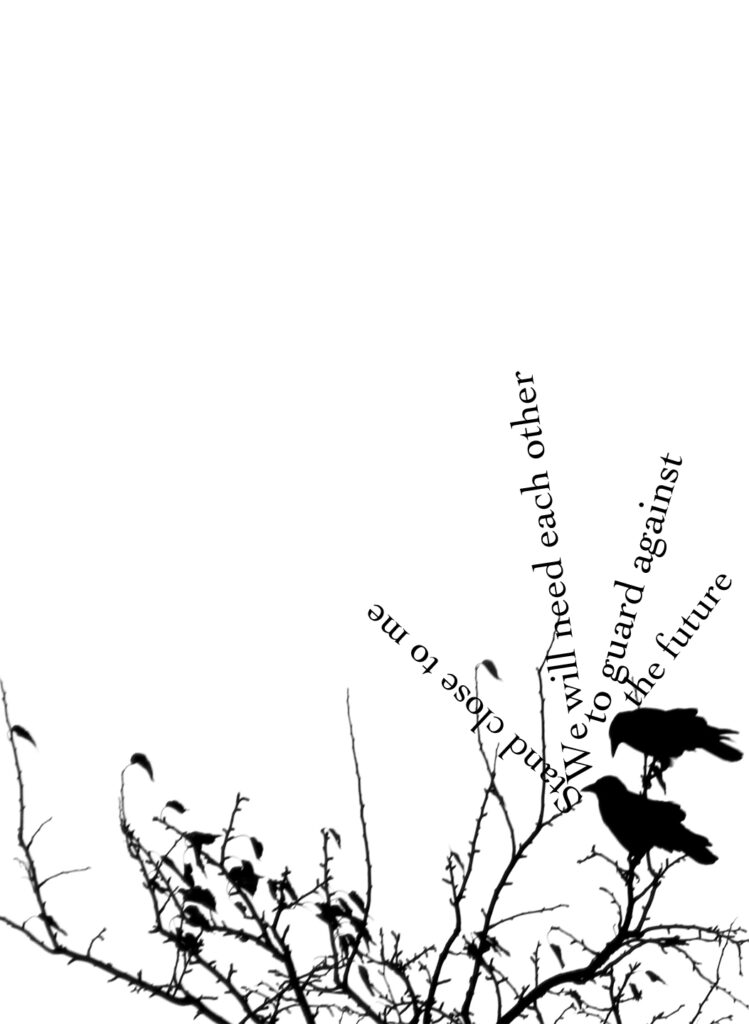

Often, a fleeting image or concept will pop into my head, and I’ll wonder: can I make that happen? The project Ozark Crows, which was excerpted here at Superstition Review, began with a single image in my mind, of two crows in the sky holding a ribbon of text between them in their beaks. The sky and trees around my home are filled with an extended family of crows, and I was already somewhat obsessed with them— their intelligence, their way of interacting with each other, ranging from the irritable to the tender. They interacted with us, too, leaving a piece of glass in the spot where we tossed out some stale cornbread, for instance. By then, I’d read so many books about crows that I was able to understand a lot of what I was observing, and this gave me so many ideas for the pieces in the book. It was incredibly difficult, and I don’t think I ever had more fun on a project. That Spuyten-Duyvil Press was able to make it into a book, and such a lovely one at that, is something I’ll always be so grateful for.

Because of my interest in place, most of the images I use are taken in places of personal significance, primarily where I live: the ground, water and sky where I’ve spent the last twenty years with my family, in the Ozark Mountains just outside Fayetteville. I think I’ve documented it to within a square inch of its life!

The project I’m currently finishing began the same way: with an image that appeared to me, and that I wondered if I could make. I love skeletonized, disintegrating leaves— I find them almost more beautiful than perfect, supple leaves. They themselves are like poems to me, a poignant memento mori. We are all trying to make something lasting and meaningful, something that can reach across time, and when I pick up a leaf with a beautiful pattern chewed into it by some infinitesimal worm, when I hold it to the sky and make a macro-photo of a tiny fragment of it, I feel like I’m participating in, acknowledging, a meaningful continuum. What if a fragment of a poem was visible through these holes? What if it was handwritten? Because I make things digitally, I want to mitigate the coldness of that form. I thought that the intimacy of the handwritten word— evidence of a human hand— coupled with the fact that the text in these pieces is so small that one has to lean in closely to glean even a fragment of meaning, I might succeed in making something that had a sense of warmth and life despite being created digitally. I am drawn to the idea that something as small as a hole in a leaf can contain a universe, or at least a poem. I’m also hopeful that, despite the crush of data we all experience, the isolation of the last year, the divisions and alienation, we can still reach other somehow.

All of this is not to say that I don’t also love writing. My newest collection, A Vertigo Book, is made entirely of words, and in fact, much of it was written during a period when taking photographs was difficult because I was suffering from a particularly terrible bout of vertigo. The words, the very shape of letters, felt like a way to hold onto the earth and keep it still, almost like bird feet clinging to a wire. And it’s probably no accident that, after months of looking up to photograph crows, the LEAF project requires me to, instead, keep my eyes on the ground.

- Art by Sarah Louise Wilson: An Interview - March 29, 2023

- An Interview with Allison Moyers - February 9, 2022

- An Interview with Carolyn Guinzio - December 3, 2021