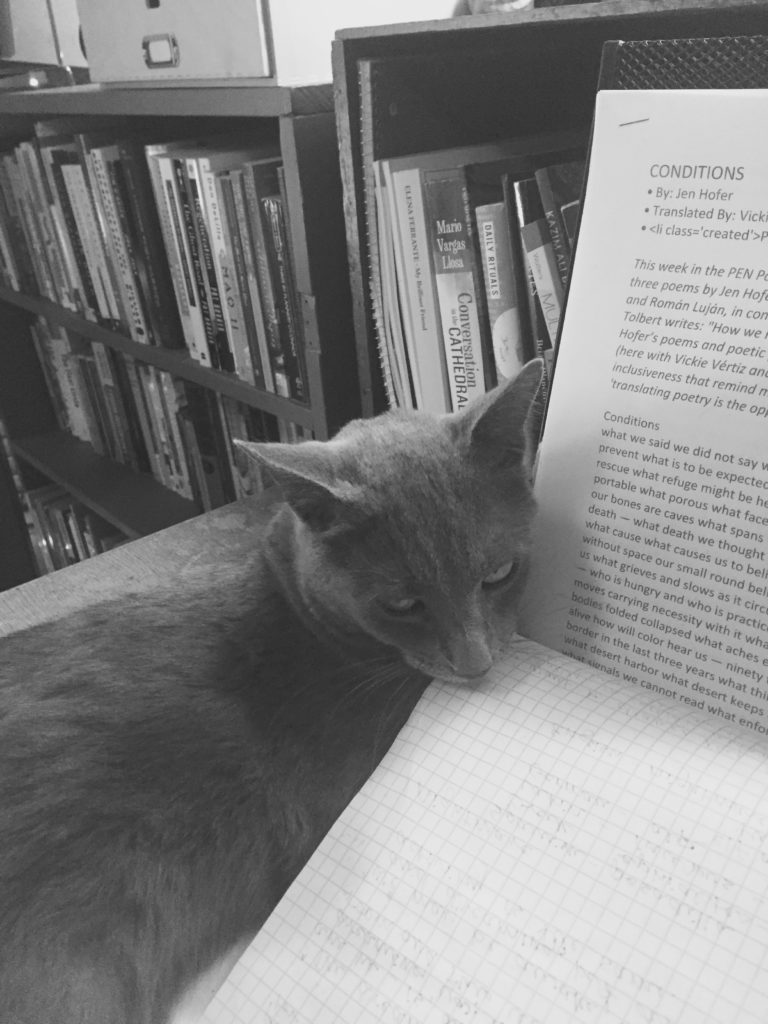

My writing study has become a lair. I have allowed two stray cats to take over the room, and there have been live lizards, fleas, decapitated birds, a wing with a gristled knob at one end, feathers stuck to the wall, smears of blood on the floor. One morning, I found two little objects on my desk chair: a tiny yellow-beaked baby finch head and a small, dark, licked-clean organ, possibly a gall bladder or kidney.

My writing study has become a lair. I have allowed two stray cats to take over the room, and there have been live lizards, fleas, decapitated birds, a wing with a gristled knob at one end, feathers stuck to the wall, smears of blood on the floor. One morning, I found two little objects on my desk chair: a tiny yellow-beaked baby finch head and a small, dark, licked-clean organ, possibly a gall bladder or kidney.

I don’t just leave the carnage. It smells, so I clean it up. But I don’t close the flap on the cat door. I leave the flap open. I let the kitties bring their viscera and alive-ness in here.

My manuscripts, in piles around the room, are marked by footprints, skittered with flea dirt.

The cats stink because the kibble I give them doesn’t agree with the beaks and eyes and skulls of rock doves. Also, they smell of the rain and the sun and the dirt outside, dirt that they track in on pee-flickered paws. The cats mew happily when they see me. Sometimes cobwebs hang from their whiskers. They are both tamed and wild. I am not much different from them.

I bring civilization, daily, to this room, and then I let the cats wild it again. I let this happen and I unhappen it and it happens and I unhappen it. Since they do not find their grisly work remarkable, I have to ceased to react to it as well. For example, I merely took the gifts of head and organ off of my chair, threw them away, and sat down. We are domesticated and wild. Wild and domesticated. We do both.

To be an artist is to choose to be uncivilized. I care about things that my society doesn’t necessarily value. I care about human expression, about art. I care about nuanced language, about writing true things. I care about humans pursuing their dreams. I value conversation above money. I value imagination above possessions. I value human connection. I have said fuck it fifteen thousand times in service to my art. Even though I want the cats to come inside during monsoon storms, they don’t care. The flap is open but they don’t always come in, even during the most raging summer storms. Lightning cracks hard, a block away, and I know they are out there, under bushes, great swaths of water rushing under their paws. They do not care that I am worried. They do not care that they are wet. They will visit later, washed, vigorous, hungry.

I hunt human life and I have bitten off its head, crunched its bones and left eyeballs staring blindly from the weeds. I have licked clean the organs of living. I have stunk up the confines of a predictable life.

Writing makes me vigorous and hungry.

Even when I don’t know what the fuck I’m doing, I can commit. I am a writer. I have to commit to projects that only exist as inklings in my heart or imagination. I have to commit to the dream of a story I haven’t written in order to write it. I have to love a story enough to write it, knowing it may never even get finished, or published, or read by another. I have devoted my life to stray narrative, ideas, imagination, to loving that which no one else might love. I believe in things that are alive and happening. I’m quite practiced at such love, at such allowance, at such potentially pointless effort. Like the unpublished works in my study, the cats are vibrant, vital stories that haven’t found homes. Always, already worthy of love.

If I close the flap with the cats inside, they scream incessantly, shred the curtains, pluck wooden splinters from the door. There is violence here, too, in my relentless insistence on this writing life. I only took jobs that allowed the writing, until I learned to make my writing fit any job. Friends who urged me to take better care of myself, as if caring for myself in this Other way did not count, were left behind. Fierce and uncontainable, I do not tolerate a closed flap.

In my twenties, I had a series of visions that made me realize that I would be a writer. I read a line in a book titled Geography of Desire by Robert Boswell, and in a moment, everything changed for me. As a character in the book gave up storytelling, I bit into it with all of my teeth. I wrote a passage in a notebook, detailing the ferocity with which I’d decided to pursue the dream of writing. Among other impassioned things, I scratched, “I do not know what will become of my normal life. This desire to write is too huge to ignore, my insides black hot hollow with need, rushing my pen across the page, my heart overworked and pounding. This is art.”

I’m interested in the last line, This is art, where I insinuate that devoting myself to the art is the art. The violence with which I commit myself is actually a work of art itself. This uncivilized act of devoting myself to something so intangible, so ineffable marks me as different, but also stands, whether I ever publish another thing, as a work of art. It is in the living that I prove myself. As the cats bring me their slaughtered, instinctual gifts, the irrepressible violence of their love, so I must offer my own vehement gifts.

My pages are torn out of the sky and the dirt like prey. Here! I’ve dragged them in for you.

The Lost Manuscript: A Particular Silence

The Lost Manuscript: A Particular Silence