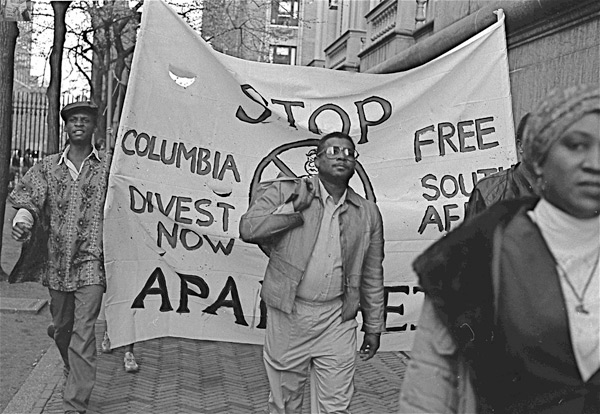

My first act of political activism was deciding to divorce my husband. He would sneer and make snide remarks every time he saw me painting and would only support my return to higher education if it was directed toward getting a job that made a ton of money. What was I doing with that guy, you may ask? It’s complicated, as the popular saying goes. Let’s just say that I got out, continued to paint, took up writing poetry when I returned to college and ended up in an MFA poetry program at Columbia University in New York, where my eyes were opened wide to a wider world of progressive politics. Columbia was the first university to divest in the anti-Apartheid movement, after Columbia students took over and held an administration building on campus for over a week. It was thrilling to be a part of this, even if I couldn’t sleep on the cold ground with the much younger undergrads. When I returned to California, I dived into art and activism both, dragging my children to anti-nuclear protest demonstrations, working for awhile as an art therapist in a mental hospital and eventually teaching art and writing in the both the men’s and women’s prisons.

My first act of political activism was deciding to divorce my husband. He would sneer and make snide remarks every time he saw me painting and would only support my return to higher education if it was directed toward getting a job that made a ton of money. What was I doing with that guy, you may ask? It’s complicated, as the popular saying goes. Let’s just say that I got out, continued to paint, took up writing poetry when I returned to college and ended up in an MFA poetry program at Columbia University in New York, where my eyes were opened wide to a wider world of progressive politics. Columbia was the first university to divest in the anti-Apartheid movement, after Columbia students took over and held an administration building on campus for over a week. It was thrilling to be a part of this, even if I couldn’t sleep on the cold ground with the much younger undergrads. When I returned to California, I dived into art and activism both, dragging my children to anti-nuclear protest demonstrations, working for awhile as an art therapist in a mental hospital and eventually teaching art and writing in the both the men’s and women’s prisons.

My first day at Corcoran State Prison, walking across the yard by myself, being mad dogged by a hefty inmate pumping iron was scary until I smiled and said hello, and he smiled and said hello back. I kept going back because I loved the work and the inmates were so nice…no, really. They were so appreciative of every little thing I did for them and it was gratifying to see women who had no visits and no money even for commissary

weaving beautiful tote bags out of strips of plastic bread wrappers. I know they weren’t saints, but I got to know them and they trusted me and told me their stories. And eventually, I wrote poems in the voices of inmates, which appeared in at least two of my poetry books, the latest one, ALTAR FOR ESCAPED VOICES, from Tebot Bach, published in 2013.

Then my full time teaching job at the university ended because of budget cut backs, (I was an adjunct with a contract and benefits…a rare species). Why did I lose my job? Again, it was complicated. But I had more time to devote to my passions: art, writing and activism.

In 2009, I accompanied a friend who was making a film, set in the homeless encampments of H St, at that time a huge mass of makeshift dwellings patched together from blue tarps, scraps of wood and odd pieces of junk, by the railroad tracks downtown, with about two to three hundred homeless residents. I was so taken with the visual tableau that I came back with my camera and ended up with a photography show at city hall. It was fascinating how they put together living spaces with scavenged metal, wood, tarps, and all manner of discarded detritus. But mostly, I was entranced with how they personalized their spaces and even decorated for the holidays. One of these photos was published in SUPERSTITION REVIEW, a photo of a Christmas tree with raggedy tinsel, reflected in the oily bilge of a dirt parking lot adjacent to the encampments.

Some years later, a friend bought a big house, with a half of an acre and opened up a transitional living shelter for the homeless. Immediately, I jumped on board and it’s been quite a ride. We have 12 to 13 clients at any given time, and we’ve learned to fly this plane in the air. But, also, I’ve met remarkable people, those who are truly at the bottom of the pile, both physically and metaphorically. And they’ve shared their stories and many of their voices have crept into my poems. I’m both amazed and appalled at how hated this segment of society is. Even some of my so called liberal friends will go on a rant about them digging through their trash or stealing copper wire from their church. I get this. But you can’t paint any group of people with one brush, and they aren’t all drug addicts or mentally ill. The homeless I know are incredible, smart, kind people who just needed some extra help. What I don’t get is how hard nosed people have gotten about helping those who are truly down and out. Yes, some have mental health issues and some have drug and alcohol issues, but let he or she whose family is without issues, cast the first stone. The housing first model works (with basic social services components wrapped in)…I’ve seen it work. And it’s amazing to see people move from dumpster diving to diving into homework or job applications. One of our residents conquered her addictions, is very close to receiving her drug and alcohol counseling certificate and is now living on her own with a part time job.

Now, I don’t want to give the impression that I’ve taken these kinds of jobs to get material for poems, photos or paintings. I think that kind of process would be self defeating. It was quite the reverse for me. I took the jobs and got involved in the projects because that’s where my heart was. One of my favorite quotes is from Charlie Parker: “If it’s not in your life, it won’t come out your horn.”

Another hero, Albert Einstein said, “The world is a dangerous place to live; not because of the people who are evil, but because of the people who don’t do anything about it.” I didn’t ever feel that making artwork was a choice for me and being involved in activist work that is meaningful is also not a choice. And it’s not complicated, it’s what I have to do because it’s who I am.