Here’s a thing. Finish your story and print. Then read that sucker out loud. Does it sing? Does it have rhythm? Have you driven all music from the mouth? Even the best of us run a few sentences to bedlam. Myself, I used to whittle, say, five thousand worn down to three. I believed I’d done the piece justice, a day’s good labor. From there, I believed, there would be little in the way of heavy editing. Just a bit of spit shine here and there.

But think back to my last essay. A good spit shine is neither about whittling nor bulking. Those are just the crude transactions we make upon the page. No, a good polish only comes through purposed editing, a thorough break down of every sentence to better fit it to the writer’s natural rhythms and voice. It’s less the work of rough demolitions, more a careful tailoring. I got another name for it. I call it filling.

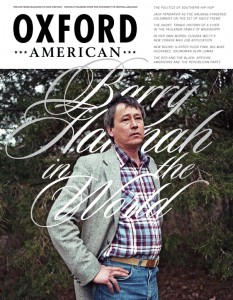

Barry Hannah was the master of filling. Take a gander at this excerpt from the Tennis Handsome:

“Please,” begged Word. “Something to eat. But no coon, no turtle, no snake.”

Daryl went to a wooden box and lifted out a whole cabbage. He walked to the cot Word lay on and slammed it down into the empty pit of Word’s belly.

Word lost consciousness.

Note the second sentence of the second paragraph. A lesser writer might be tempted to trim some of the fluff from that sentence—“the empty pit of”—to get what many of us seek: tight, concise sentences. But such a cut destroys the music, the tone. The threatened clause lends a layer of detail to the scene, informs us on Word’s condition, his gauntness, his privation. When taken with the dialog it’s altogether pleasant medicine whose effect is felt in the belly, the ribs. The next sentence, broken into its own paragraph, is effect. Word blanks out. So too the narrative eye, switching lenses in the following paragraph to the abusive captors until a sudden shift sends us back.

Filling must be used cautiously. That’s about as close to a hard rule as I like to get on it. But I’ll go a step further: filling must be used to preserve the natural rhythms of the storyteller provided it does no harm to narrative functions (plot progression, character development, and so forth). That’s a good deal clunkier than I’d like but you get the idea. Filling’s not about the length of the sentence. It’s about delivery, tone, rhythm. It’s about music. No coincidence music played such a big part in Hannah’s life and stories. The man understood that a good ear for rhythms and melodies, pitches and refrains and all the many parts of a good tune make for a perceptive writer. And mind, I don’t mean perceptive in the traditional sense, that of the eye, the voyeur. I’m talking something else entirely, an awareness of and fondness for space, for sound. I mean a real love for the music of human beings, human things.

What makes Hannah’s work so unique is the abundance, the clarity of the man’s music. It’s in every sentence, rich but never saccharine. Good writers pull it off once or twice per book. Hannah threads it in every sentence. In the strictest sense, his beats are up tempo, somewhere in the range of one hundred and ten, twenty. Unlike Baldwin, Hannah is pure rock and roll, aggressive and driven and rarely cacophonous save for the finer moments of entropy. Late in The Tennis Handsome Mr. Edward, father to French, struggles to get his mind straight. He’s got animals upstairs, a naked wife, beauteous. He’s got noise. He leaves on a rather apt note:

“Mr. Edward’s eyes went shut again.

Olive, the music.”

But here’s a thing in closing. I don’t think such music is beyond the ken and craft of other writers. We can learn from Hannah, take his lessons to heart. We may not have Gordon Lisch but we have Hannah himself. We can break his sentences down, figure out the notes, the melodies. We can ask ourselves probing questions. Where is my music? Where are my notes?