The South’s a weird place. Don’t tell me otherwise.

I spent twenty years mucking about in Florida, various parts. A few in Gainesville, a few in Clearwater, a whole bunch in sleepy New Port Richey with its crab shacks and pawn shops and dangerous proximity to US Interstate 19. You’ve never seen a more dangerous stretch of state pavement. Drivers fall to its rhythms, froth with rage. They seem destined to ram something—each other, poles, the titty bar. I’ve been struck by all manner of vehicle while en route. There was a garbage truck, a limousine, a sleek silver scooter no bigger than ninety in the engine. The pilot, a small woman with frosted hair and aviators, came right up to my window and struck me with her sandal. She was barefoot on scorching asphalt just to make violence and she hit me. The whole time she wanted to know what my problem was, where I was deficient. Did I or did I not see the sign? Was this a turn lane? Who was I?

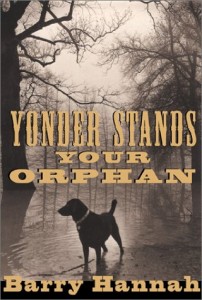

That episode, quite real, seems tame compared to what happens in Barry Hannah’s fiction. Take the deranged couple across the lake in Yonder Stands Your Orphan, the orphans themselves, their heavy armaments. Is their assault on the barge, their curious fortifications truly otherworldly? Is Man Mortimer, the deranged antagonist and protagonist of the novel? How about Ned Maxxy and all his watching, his secret touches? Part of what makes Hannah’s work so vivid is the wild imagination at work. Therein lies a peculiar weirdness, one drawn from the strange fiber of the South. This was, after all, a region punted into mechanization after a prolonged and staggered war, a hot bed for carpetbaggers, post-Reconstruction vultures. Is it any wonder madness takes up so much of the stage in Southern fiction? My own theory points to the move from the rural to the urban. It just didn’t take, not like the North. We’re dealing not with two minds but many, cracked prisms with twangy accents.

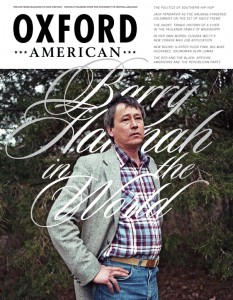

But the weirdness in Hannah teaches far more important lessons to the wary student. The first is that imagination unleashed is a boon, not a hindrance, to the writer with genuine talent, grit, heart. There’s no accounting for all the movements of Ray. You flat out couldn’t outline it. What you get are characters with desires, a thing sadly lacking from much contemporary fiction. Then you get the land, the richness of the place around them. But that’s not on the page, in the paper. It comes from the characters, first and foremost. It springs out of their eyes, their mouth, all the little movements. More than tact, it’s nuance. Gordon Lisch taught Hannah how to trim everything down to the proper rhythms, but the rhythms come from the characters. That’s where we who pretend to the pen need to sit up and take notice. Did your story, your book, spring from your character? Or have we built everything in lieu of them, a way of explaining who and what they are? The latter, we learn from Hannah, is folly, the bone road.

Too, we learn the difference between volume and clarity. This one’s a doozy. How many of us have powered through a workshop (MFA grads, y’all know, oh yes) and heard some cabbage head say, “I want to know more about this character.” This is said with total sincerity, great caution. So and so practically simpers as speaks, paws the desk. Were it allowed, he might lick the table, taste the salts of human nearness. Meek as a doe. And you might be tempted to revise, add in another paragraph or two or three and ruin an otherwise good piece. Because it’s not about volume, friend. It’s about clarity, precision. Go back to your Hannah, The Tennis Handsome. Pick up on Professor Word after French ruins him on the court:

A nurse and a man in white came up to quell the noise from Word. Levaster went back into the closet and shut the door. Then he peeped out, seeing Word and his brother retreating down the corridor, Word limping, listing to one side, proceeding with a roll and capitulation. The stroke had wrecked him from brain to ankles. It had fouled the center that prevents screaming. Levaster could hear the man bleating away a hundred yards down the corridor.

Five tidy sentences are all that’s required to understand James Word post stroke. Much could be made of this neat paragraph, even more extracted in craft and technique. But precision is what we’re after if for nothing more than to silence the cabbage heads. What better way to deliver the weirdness of the South and its many inhabitants than a targeted strike, word by word, into the very heart of the thing?

How’s this for targeted. After that woman beat me with her sandal I didn’t know what was what. I never got her name or insurance, never called anyone. There wasn’t even a dent. At home in the mirror I glimpsed the red imprint of her sandal, a swath of dirt across my face. I might have loved her. I hung around the intersection hoping her scooter would plow into me, mar the door, bust a window. I was ready with a baseball glove, a pen and some paper. The plan was to ask her out, make sweaty love, marry her. But it wasn’t to be.

A month later I saw her at the store. She was buying pickles, all the varieties, a whole cart full. I went up full of my own juice, testy, moral. She didn’t recognize me. Just gave me the eye and went on with her shopping. Me, I slithered away. I went home and checked myself into a chair with some beer. There was no accounting for it. What a weird, weird way to live, to love.