Regardless of our life circumstances, we each have a biological mother and father. 50% of our genetic make-up comes from Mom, and 50% comes from Dad. But as writers, we also have another set of “parents.” They may be living, or they may have died decades, even centuries ago. They may come from another country or write in a foreign language. We may not agree with their politics or life choices, nevertheless these other parents influence our lives. They are the poets and writers who have shaped if not our genetic futures, then certainly our creative destinies. These special parents are not simply the writers we admire―they are the writers whose work has turned us inside out, touched our souls, and changed the way we put pen to paper. Often, we recognize our creative parents immediately and instinctively. Sometimes, our connection to them becomes evident only over time.

My poetry “Mom” is Anne Sexton. Although I’d written as a child, I returned to writing seriously as a wife and mother during the decade when feminist and confessional writing flourished. Involved in both undergraduate studies and an ongoing women’s writing workshop, I was taught that nothing in a woman’s life was out of bounds. Suddenly, it was okay to write about our most intimate bodily details, about our psychological struggles, our families’ flaws and our innermost yearnings. Of course, reading Anne Sexton was required. I admired her poetry for its boldness and its craft, but I didn’t recognize her as my poetry mother until a few years later, when I was about to graduate, finally, with a BA in English and a minor in Creative Writing.

It was late, maybe midnight or 1 a.m. My husband and my two children were sleeping, and I was in the family room, curled in a chair, laboring over a poem that wasn’t quite working. I was deep into that space we writers can sometimes enter, that place in which time is meaningless and there seems to be an open conduit between our unconscious mind and our hand. Pausing in my writing, I felt a presence enter the room. It was clearly feminine, and generously approving. It seemed to surround me and―perhaps because in that mysterious space we have access to understandings that elude us otherwise―I knew, in my very marrow, that this presence was Anne Sexton. Then and there, she claimed me.

She’d died by her own hand in 1974, years before this visitation occurred. I was already moving away from purely confessional writing, sensing that some events were better left to memory or exploration in a private journal. And, at that point, Sexton wasn’t even my “favorite” poet. Maybe I’d been half-asleep or dreaming. Regardless, in that encounter, I was infused with a deep recognition. There was, and is, something about her ability to blend the formal with the personal, the way she risks the edge in her poetry, and how her poetic voice is both vulnerable and determined, that captured me. Her presence faded, and I returned to my poem; new, just-right words easily led to a perfect closure. Since then, when my poetic bravery wanes or my poetry becomes too staid, too bland, I return to be nourished by Anne Sexton’s poetic strengths.

Wallace Stevens is my poetry “Dad.” (Imagine that marriage, Anne and Wallace debating the purposes of poetry over dinner!) Again, although I’d read volumes of Steven’s work as an undergraduate, it wasn’t until I was doing graduate work at New York University that I recognized Stevens as my creative father. One of my teachers, Galway Kinnell, required regular memorization of poems. We had to absorb every word, every line break, every punctuation mark, and so be prepared not only to speak our chosen poems, but also to transcribe them perfectly. One week, I chose Stevens’ “Peter Quince at the Clavier.” If you don’t know this poem, find it. Read it. Get lost in it. That’s what I did, and in the process some of Stevens’ poetry DNA became mine. After I recited the poem, Galway Kinnell said, “His rhythms seem to suit you perfectly,” and I could feel it too. It was as if Stevens’ poetic constructions―the placement of his line breaks, the mysterious underbelly of his stanzas―fit into my own creative sensibilities like a final puzzle piece locking into place.

There were other factors too. Stevens had a day job, as I did. His co-workers didn’t know he was a poet, and neither did mine. He embraced a certain privacy and orderliness, evident in his poetry, and yet that order worked to amplify, in a paradoxical way, the secrets and tensions that lived beneath the surface. In “Peter Quince at the Clavier,” Stevens suggests that it’s the misery of not having poetry, of not having something beautiful in your heart, that might be fatal to the human spirit. When my poetic music threatens to fade, or my poems seem too superficial, lacking that lovely “touch of strange,” I return to Stevens, especially to that poem I memorized so long ago.

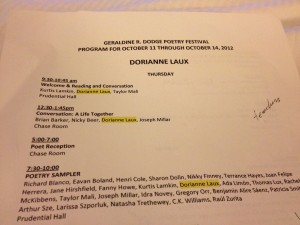

Maybe you have also discovered your creative parents along the way. Artists too have creative parents, and it’s not unheard of for a writer to have an artist or a sculptor as his or her creative parent. Happily, we can even assemble entire families. Although in reality I’m an only child, my poetry sisters are Sharon Olds and Dorianne Laux. My poetry brother is, without a doubt, Henri Cole. My poetry aunt, on my mother’s side, is Louise Glück. My poetry uncle, on my father’s side, is Yehuda Amichai. My favorite poetry cousin is nurse-poet Jeanne Bryner. An eclectic family indeed, but wholly mine. And while I honor them differently than I honor my actual relatives, I return to my creative parents and siblings again and again, for guidance, for reassurance, and simply for the pure pleasure of being in their company.