A passage in Dylan Thomas’ A Child’s Christmas in Wales has been rattling around in my brain this past month. The house next door (“at the bottom of the garden”) catches fire, and the bored children joyously race into the smoke armed with snowballs until the fire brigade shows up to put the fire out.

“And when the firemen turned off the hose and were standing in the wet, smoky room, Jim’s aunt, Miss Prothero, came downstairs and peered in at them. Jim and I waited, very quietly, to hear what she would say to them. She said the right thing, always. She looked at the three tall fireman in their shining helmets, standing among the smoke and cinders and dissolving snowballs, and she said, ‘Would you like anything to read?’”

Miss Prothero, blinking through the noise and mess, offered to make order of the crazy world. And it’s funny because human beings are absurd. But aren’t readers and writers order-makers of this ridiculous, unfathomable world?

November 9th dawned bitter cold here in Central Vermont’s stick season: a world of bare black-limbed trees, smoke gray skies, stubble fields. I walked downtown to have breakfast with a friend through streets the quiet of deep mourning. The restaurant was closed; my friend told me later the owner couldn’t open because her kitchen staff is all from other countries, and they were too panicked to work. She’d spent the day with them, listening, promising advocacy, reassuring.

I spent the rest of the day wrapping my trees and bushes for winter. Pounding garden staples into already hardened ground, a leaden sky reminded me that bad things happen all of the time. People get shot, people have been hung, people are herded into camps or prison under bright skies, under gray, on sweet spring days, and in blinding winter storms. Bad things happen and then the sun rips a hole in the clouds, as it did that afternoon. A fat blue hole rimmed with brilliant cloud. My fingers were frozen by that time, I’d used up all the staples and burlap, and had nothing left I could do to protect my tender garden. So, I leaned on a dirty shovel and watched the sky for awhile. I didn’t forget the election results, but for a moment, I forget my anger and my dread. Bad things happen and then something good happens and gives the courage to go on.

In college, I took logic, hoping, wrongly as it turned out, that it would meet the math requirement. Professor MacEwan made it abundantly clear we were lucky to be in his class and, if we got something out of it, that was on us. A dried up Scot who favored tweed sports jackets and starched shirts through all weather, he spent several weeks forcibly dragging us through syllogisms: “If P, then Q. . . and therefore . . .” He wrote each equation on the blackboard in squeaky chalk while we mostly lolled in our seats, drinking coffee or sleeping, this being well before the age of devices.

But, one day, he lit up like a prizefighter, and all but shouted at us, “I want someone to prove to me there is water in the gorge.” What gorge? What was he talking about? But suddenly, several of the lumpy guys who’d been slouching in their seats like corpses all semester, removed a couple of layers of sweatshirts and actually spoke, “There’s no water in the gorge!” cried one of the lumps, lifting a fist heavenward. Another lump shouted back, “I say there is!” And, with that, the fight was on. As the only woman in the class, I picked my battles in that male dominated world. This, I decided, was not my fight. I sat back, sipped my bad coffee, and watched the melee unfold.

The guys took sides and took them seriously. T-shirts cropped up all over campus emblazoned with either “There is no water in the gorge,” or “There is water in the gorge.” In class, Professor MacEwan, smiling his thin smile, whipped the arguments on each side into lathers of frenzied belief that teetered on rickety architectures of proof. Winter ebbed into spring and still there was no conclusion. When May came, we got our grades, and the arguments dissipated into the Sacramento heat, unresolved, irresolvable.

This fall, during and after the election, I thought back to that class, wondering about the problem of debating something largely imaginary. Of course, most of what we believe is based more on emotional logic than anything else. And that, perhaps, was Professor MacEwan’s point. At our core, the philosopher Iris Murdock wrote, “human beings are anxious, squirrelly creatures.” We’re a bundle of need with an ability to make swords out of what we pay attention to. The confluence of attention and desire creates the aperture for belief. And then we go about hurting each other with those swords made of words.

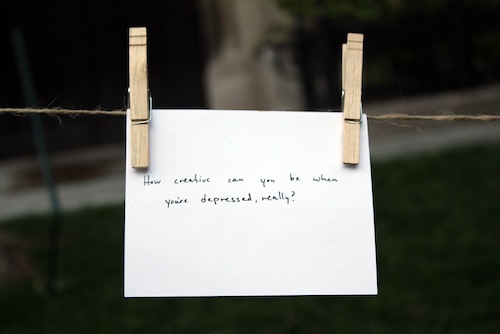

So what about the job of writers? Advocacy, a call I do embrace, is more than merely taking sides. Our charge, I think, is to speak about the world and our experience of it, at a deeper level of truth-telling. As our country, so torn right now by warring beliefs, struggles to make sense of, or find hope in, the results of this most contentious political year, where is our common humanity?

As a young person, I dreamed of that common language Adrienne Rich spoke of as something that might heal the world. I dreamed it could heal me. I dreamed, just as Professor MacEwan posited that gorge, because I needed to. I needed to imagine that, through evil, through grief, there is a ground of meaning. That the cracks, as Leonard Cohen wrote, let in the light.

Whatever the common language is, art is its voice. And it’s not about being saved or cheered up or things working out. If there is a gorge, sometimes there is water, and sometimes not. If we are all human beings, we need each other and we need art. Barry Lopez wrote, “sometimes we need a story, more than food and drink, to stay alive.” (from Crow and Weasel.) The story I want to tell invites the imperfect, the vulnerable, the tender, and the absurd.

For that reason, of Thomas’ unforgettably quirky characters, I think I would choose to be Aunt Hannah who shows up at the end of A Child’s Christmas, and who “got on to the parsnip wine and sang a song about Bleeding Hearts and Death, and then another in which she said her heart was like a Bird’s Nest; and then everybody laughed again.” And then the author goes to bed.

We do the best we can to speak from our hearts and hope we’re received without acrimony, with some measure of forbearance, or kindness, or even love. So, let’s you and I read and read, and write and write. You let me know when you’re ready to speak. I’m listening.