It’s National Poetry Month and I’m focusing on ekphrasis. When I mention this to people, even fellow poets and writers, I usually am met with “ek-what?” Ekphrasis is a term used to denote poetry written from or inspired by visual artistic mediums and traces its lineage back to the Greeks and Romans, including the works of Homer’s The Iliad and Horace’s “Ars Poetica.” The word ekphrasis, in fact, comes from two Greek words, ek, meaning out, and phrasis meaning speak. Ekphrastic poetry, then, functions as a “calling to” or “speaking to” (or about) art.

Historically, conventional forms of art, as seen in Robert Hayden’s “Monet’s Water Lilies,” and “Archaic Torso of Apollo” by Rilke, are central to traditional ekphrastic poetry. However, in the last few decades, many reservations have been raised about the use of ekphrasis in poetry; mainly, that it limits the poet’s ability to seebeyond the work itself.

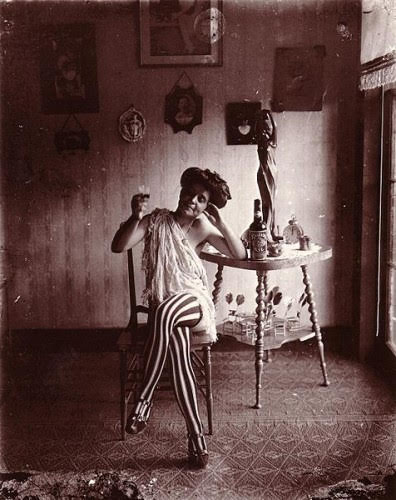

Oh, I disagree. Ekphrastic poetry is not just a celebration of art—in all of its forms—but is limitless, in fact, in its scope. The poet may choose a photograph and discuss the subject, yes, but more than that, may choose to write about the photographer one can’t see in the image, or capture something partially exhibited in the background, or simply use it as a source of intellectual and artistic inspiration.

The problem with this argument, and those like it, however, is that when discussing ekphrasis, critics often conjure images of someone entering a gallery exhibit and then rushing home to write a poem about it. This argument, sadly, sells the practice of ekphrasis short. True, there are numerous poems in the vein of I just saw the Van Gogh exhibit and now I have to write a Starry Night poem, but the beauty of ekphrastic poetry is the dialog it creates between artists: poet and image, poet and painter, graffiti artist, jazz musician.

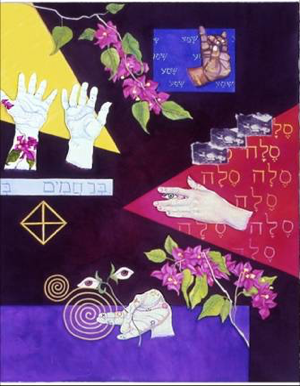

Notable collections such as Natasha Trethewey’s Bellocq’s Ophelia, Kevin Young’s Jelly Roll andTo Repel Ghosts, Sharon Dolin’s Serious Pink, and Joseph Campana’s The Book of Faces are ekphrastics that speak to an entirely new generation of readers and poets. These poets and their works are helping to bring the ekphrastic out of the museum and gallery and into a new century where the image is dynamic, where the concept and definition of art is limitless.

As the Greeks and Romans utilized the ekphrastic as a means to understand their fellow human and their place in the universe, so do contemporary poets such as John Ashbery, Sharon Dolin, Kevin Young, and Natasha Trethewey. In a modern era, ekphrasis is not limited by tangibility, but by the possibility of what the artistic media can encourage. Many successful modern ekphrastic poems bring the tradition into the new millennia by opting to utilize contemporary media as a means to reflect a modern, often skewed and distorted culture and thought.

In Kevin Young’s collections, To Repel Ghosts and Jelly Roll, Young’s poems are inspired by the blues and the experimental African American artwork of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Similarly, Jeannine Hall Gailey’s poems in Becoming the Villainessare concerned with the modern image of the objectified woman, using the artifice of female comic book superheroes and pop artist Roy Lichetenstein’s women to explore the role of female characters in a culture so visually consumed.

Today’s ekphrastic is not an expected recreation of Rembrandts and Van Goghs, but function as a call- and-response to the media and images of a dynamic, contemporary culture. Music, film, comic books, and pop art are all integral to the way we think about the world around us, our interior and exterior landscapes.

Art exists to hold the viewer and the subject of the work in place, in a moment in time. In this, both the viewer and the object are always present. Beyond the description of a painting, a blues song, or a film, ekphrasis is a work of detail and experience, with the poet’s implement of perspective bridging the gap between the real world and the imagined.