Got Ekphrasis? Conversations Among Art Forms

Who doesn’t want to feel exhilaration, even transformation, during their creative writing process? Often when we are writing alone we get trapped in our own obsessions, verbal tics, repetitive images, “go-to” metaphors; and sometimes we just come up empty. Perhaps we can enhance our creative process by allowing another artist to speak into our imaginative space. Yes, it often feels risky but the rewards can be great.

I am speaking of the practice of ekphrasis, a conversation between and among two or more art forms. Working within an ekphrasis framework, some poets are using visual art, music, photography as well as mathematics, philosophy and physics to enhance their creative process and transform their finished work.

Ekphrasis can be viewed as an active, rapid interchange of the unexpected. It requires an attitude of openness and vulnerability. Ekphrasis courts the unanticipated.

My own experience with ekphrasis involves working with visual artists and musicians, some of whom I collaborated with for more than 10 years. When I first began working this way, my initial responses were nervousness and fear. I didn’t know how my collaborators would receive my work—or if they would understand my vision—or if they would try to impose something on my imaginative space that would feel false and intrusive. And I was also afraid that I would do the same thing to them! However, mid-way through my first collaborative project, what I discovered was that my fears were unfounded. In fact, my collaborators affirmed my poetic vision and enhanced my process by offering unexpected but thoughtful and useful suggestions about my work. Their reactions to my process and to poems allowed me to “think bigger” about my whole body of work. They saw things in me and my work that I could not otherwise see.

Significantly, I learned the approach to ekphrasis projects often centered upon these two dynamics:

- Focus on structure or form

- Focus on theme or content (essence)

I have worked with artists on numerous ekphrasis projects. However, I collaborated with two artists far more than any others.

With visual artist Beth Shadur, I have worked for more than 10 years on a multitude of artistic adventures. Beth founded and curates the Poetic Dialogue Project (for which I am the poetry curator), an ongoing project pairing visual artists with poets to make collaborative work. Its exhibitions have traveled nationally and internationally.

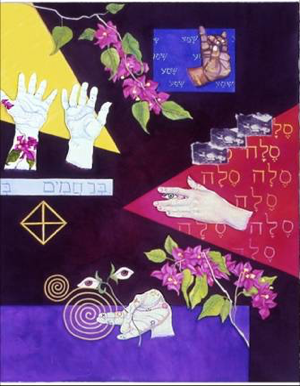

During our collaborations, Beth and I would often talk about how the “rhythms” and “structures” in a particular visual art piece matched the rhythms and structures of a particular poem. For example, here is Beth’s work “Witness,” which she created in response to my anti-war poem “Bougainvillea and TV.” If you look closely at this painting, you can see part of my poem and my name embedded on the palms, in the upper left hand corner of the picture. My poem is written in free verse with short lines followed by longer stanzas. Beth’s work has similar rhythms of color. My poem ends with the lines: “Now I know I will never understand a thing./The world talks only to itself./Rain to War. Child to dirt/Bougainvillea and TV.” Notice all Beth’s multi-cultural symbols of peace alongside the embedded image of the child lying in the dirt, which is a response to those lines. Both the poem and the visual art retain their own integrity but each is clearly “in conversation” with the other.

Beth explains the transformative power embedded in the ekphrasis framework that she heard from her many Poetic Dialogue Project collaborators:

“Poets mentioned experimenting and working outside their own comfort zone to create new ideas and forms for their work, while artists who had never considered text as part of their work found ways to integrate the poet’s voice. The ongoing dialogue offered each creator the opportunity to witness and effect the creation of ‘the other’, respond, communicate, argue, compromise, and sometimes, to change or overcome difficulties. In making collaborative work, each individual brought his or her strength to the paired collaboration, allowing each contribution to be weighed and valued, given critical consideration, as the pair moved to develop solutions to the creative process as a team. In some cases, the collaborative effort was exciting and inspirational, in others problematic. Some pairs mentioned difficult struggles in working with a person who was a stranger; and yet struggle, too, is part of the creative process. All pairs found that the collaborative process in creativity became a catalyst for new directions, new forms and new paradigms in their process and practice.” http://bethshadur.com/the-poetic-dialogue-project

The other artist I worked with was composer Christopher Scinto. He and I collaborated on the creation of a music drama, The Ballad of Downtown Jake. Christopher wrote the music and I wrote the book and lyrics. “Jake” is based on my collection of poems High Notes, the writing of which was a direct result of our collaboration.

When we first began working on our project, Christopher and I would talk about the way the structures of jazz pieces—“riffs”—can be mirrored in the structure of poems and a poetry collection. Christopher suggested we create five characters based on his anticipated musical considerations, which he would refer back to when writing his musical score. We decided the core conflict of our characters would be a differentiated struggle with addiction. A short while later, I named the characters and wrote a five-part poem titled “After the Jam Session.” The refrain in the sequence was a riff on the line “Give it to me,” which later became a kind of guiding principle for us. We decided each of our characters was addicted to something— whether it was fame, love, justice, power or hope. Ultimately, we realized we wanted to address the essence of those addictions in terms of the sacred and the profane and the role it plays in the creation of art.

Watch The Ballad of Downtown Jake here.

Working with these artists transformed my poetic process and my poetry significantly. However, the most important gift I received from working with artists on these projects was joy: The pure delight of creating. The simple delight in discovery. The excitement of invention. The elation along the journey. The transport of another’s imagination. The experience of living art.