Transcending the Particular: Why All Stores Do not Matter Equally

Shakespeare and I have far less in common than meets the eye.

Shakespeare and I have far less in common than meets the eye.

On the surface, we’re both Caucasian, male, reasonably well-off for our times, and, in the eyes of my students, roughly the same age. And, as it happens, we also write plays—although his have received a somewhat more enthusiastic reception. For the time being, at least.

That’s roughly where the commonality stops. Shakespeare was English, and left countless artifacts to prove it, as every huckster in Stratford-upon-Avon will assure you. Meanwhile, in Shakespeare’s day, my forebears, a motely crew of impoverished fishermen, brick layers and subsistence farmers, struggled to survive the brutality of the Russian Pale. They practiced a rigid breed of Orthodox Judaism, spoke Yiddish, and suffered the brutality of Cossacks. Novels and plays were likely as alien to them as the church bells of London. Later, those relatives who survived the Pogroms found their way to the gas chambers of Poland. To describe Shakespeare’s drama as my cultural heritage, merely because of the demographic characteristics enumerated above, would reflect the worst of whiggish anachronism.

I emphasize this context, because I want to explore an argument advanced by a Sacramento high school English teacher, Dana Dusbiber, in a Washington Post op-ed last summer, in which she argued against assigning Shakespeare to her inner city students, a majority of whom are low-income kids from minority backgrounds. She wrote:

“….I enjoy reading a wide range of literature written by a wide range of ethnically-diverse writers who tell stories about the human experience as it is experienced today. Shakespeare lived in a pretty small world. It might now be appropriate for us to acknowledge him as chronicler of life as he saw it 450 years ago and leave it at that.”

I do not mean to dismiss the entirety of Dusbiber’s argument: Certainly, students should be able to relate to the literature that they read and a strong case can be made for allowing young people a say in designing their own curricula. Having exposure to literary role models with whom they can connect is essential if we are to welcome a diverse generations of future writers. My concern with Dusbiber’s column is that it does not just dismiss Shakespeare, but embraces a philosophy, increasingly present in literary circles, that writing does not transcend context. One might as easily argue—and I think this would prove a grievous error—that Frederick Douglass lived in a remote antebellum world of chattel bondage, so why read a slave narrative? Or dismiss the distinct rural feminism of Willa Cather, because nobody dwells in sod houses any longer. What makes great literature, as I see it, is precisely the opposite: The ability to capture your own “pretty small world” in a way that speaks to people nothing like yourself.

One need not be African-American to be moved by Richard Wright’s Native Son or Jewish to connect with Bernard Malamud’s The Fixer—or, I’d like to hope, to see the commonality of experience endured by Bigger Thomas and Yakov Bok. The joy of reading lies in recognizing the universality of human experience lurking within the particulars: seeing your own tedious cousin in Jane Austen’s William Collins or an ex-girlfriend in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Jordan Baker, or, I have no reason to doubt, a friend or acquaintance lurking in the great oral narratives of Latin America or Southeast Asia—even though one has not grown up in 19th century Britain or Jazz Age Long Island, has never stepped foot in the Andes or the Mekong Delta. When in Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook, she describes the “long littleness of life,” I understand instantly, even though my politics and lived experience might prove closer to Shakespeare’s than to hers. Whitman’s “multitudes” may be vaster than my own, but the moments of overlap leave me breathless. Growing up as a Dumbo-eared, funny-looking child with a lisp, I remember discovering Pecola Breedlove in Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye and feeling a deep kinship with her—not to suggest, obviously, that my suffering was anywhere as severe as hers, but I cannot emphasize enough the solidarity, and solace, I found in our parallel fantasies.

Great stories look outward. What is the point, after all, of speaking to people who share your own values and experiences and sensibilities? I wish to emphasize very strongly that this observation is not directed only or primarily at minority writers. Quite the opposite. Far too many of today’s celebrated A-list literary figures are upper-middle class white men who write specifically for people precisely like themselves. (Brooklyn Heights, I hear, crawls with them.) They are often enabled by a publishing industry populated by editors who share similar lived experiences. That is not to say that one cannot cull worthwhile, transcendent truths from Sutton Place or Westchester County—as, for example, does John Cheever—but that many authors no longer seem to be trying. Similarly, a resistance exists to reading about people different from ourselves, or to do so primarily to witness their differences, in lurid exoticism disguised as open-mindedness, rather than to enjoy our similarities. So much of publishing has become inward looking—about marketing to specific audiences, branding, and targeting insular literary communities. I want my students to write for people as unlike themselves as possible. The stories that matter most, at least to me, are not those that merely capture an unknown world—but those that bring me a world I do not know and teach me how it reflects or connects to my own.

With increasing frequency, when I speak at conferences or on panels, audience members ask some variation of the question: Can I write effectively about people whose backgrounds and lived experiences are fundamentally different from mine? (It is worth noting that the questioners tend to by an extremely diverse lot—far more so than the audiences at these events.) To my surprise, and dismay, authors I admire are increasingly answering “No.” I think this approach is misguided, but also tragic. Needless to say, it is much harder to write about cultures and experiences distant from one’s own—and the room for error is significantly greater. Exploration is not an excuse for carelessness or stereotype. But do we really want to create a literary world where the next Tennessee Williams or Edward Albee can’t write about heterosexual couples? Or in which William Styron, whose Sophie’s Choice rivals The Diary of Ann Frank as the most compelling of Holocaust narratives, confines his intentions to Tidewater Virginia? I believe we should be encouraging our students to write about people far different from themselves—to hope for empathy rather than to fear appropriation. (This is a distinct issue, I believe, from the serious problem of the chronic underrepresentation of certain stories and groups in mainstream publishing, but the two matters are often—and, in my opinion regrettably—conflated.) I dream, maybe naively, of a world where we tell each other’s stories, and do so with such insight and identification, that they truly become our own.

So back to Shakespeare.

A host of plausible reasons exist for reading less Shakespeare. But I’d hate to believe that one of them is that he doesn’t speak to low-income minority students. To me, that sells those students short. I’d hope that their teachers can find a way to show the relevance of Hamlet’s doubt or Macbeth’s ambition to their own lived experiences, much as my teachers were able to do for me. Obviously, students of all backgrounds should also be introduced to the universal human experience found in writers who “look” nothing like Shakespeare. But there’s a magic to discovering that someone very much unlike oneself—let’s say a playwright who lived on a distant island more than four centuries ago—shared recognizable fears and longings.

If literature cannot bring us together, what can?

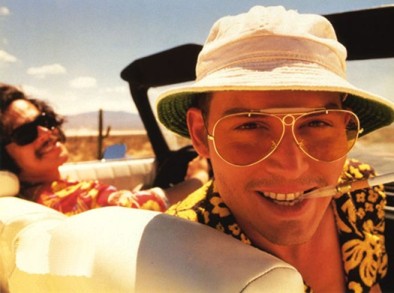

Similarly, in his infamous novel and “love affair with the English language,” Vladmir Nabokov’s protagonist Humbert takes his underage lover in a long road trip across the United States in Lolita.

Similarly, in his infamous novel and “love affair with the English language,” Vladmir Nabokov’s protagonist Humbert takes his underage lover in a long road trip across the United States in Lolita.