THE MEANING AND THE MAKING: A thesis on painting and process.

I know a lot about the process of getting saddled. Brushing the horse down so there are no slivers or pieces of hay stuck to mud or sweat on their backs where the saddle blanket will go and later the saddle, breast collar and cinches. When you first heave the saddle up, you will settle the piece over their withers. Kind of rocking it up so that it sits on their back in the right way, with the curve of their spine. Taking the halter off, stick your finger in their mouths to tickle their tongue. They will open up for the bit and bridle to be placed. The way a horse will purposefully fill their belly with air to keep the cinch looser is funny and predictable. You have to ride them out a little. When you dismount to open the first gate, then re-tighten the cinch.

My addiction is work. Through process and action meaning is found. As kids, knowledge was acquire by virtue of physical labor and watching our parents work. “I can sleep when I’m dead”, my grandfather used to say, meaning if there was enough light left in the sky he ought to be outside being productive. Constantly being engaged in activities with a physical sequence, my mom would till the garden, can tomatoes, and haul cords of firewood to the house for winter heat. Feeling guilty for taking downtime and sitting still, I feel my art should be done with much rigor. Having the common mindset of a hard working, labor-intensive ranch community with several Hutterite colonies surrounding you from birth, a certain addiction gets instilled in a person, mine is work.

Beginning my work, I buy wood and the supplies needed to build a frame for the canvas I will later stretch by hand. Laying the painting on the floor and using a squeegee, I move thick layers of gesso over raw canvas. A tinted ground is created by adding paint directly to wet gesso. The gesso dries leaving what will become the underlying textures and color. The painting begins its journey into being an individual.

Resolve and agreement come through time. Becoming its own entity with a unique personality, the piece starts to demand that certain decisions be made. The dialogue is back and forth; as the painting informs me, I make suggestions to it. Physical struggles and gaps in communication make up the relationship, as well as harmony and good rhythm. When an understanding is achieved and the image becomes clear, I am able to more meticulously mix colors and infuse specific forms into the painting. Many times it is this process that will bring me to the paintings namesake.

Important to my vision is creating paintings that are not overly contrived while finding a balance between control and chaos. Allowing a paint spill to meander across the expanse of canvas without altering its path is a way of letting chance in. Reacting to the layers of spilling, I will cut directly into masking tape or use spray paint to further reinforce or abstract a form I have found. This is control. Going through a full day or two of this process can lead to an impasse with the work. At this time something drastic must be done which can cause the painting to relapse back to a juvenile state. A body of paint is created with a skin that retains its memory of mistakes and of being made.

Editing is a huge part of the process in the making. Knowing when something is finished was once one of my weakest qualities and I am heartbroken over the loss of many images. Due to insecurity, these images have been buried under unnecessary layers of paint. Leaving a section untouched is equally as valuable, if not more so, than adding elements. A delicate balance exists between the work being finished and the painting lacking. Taking risks, making decisions and committing myself to the changes are essential. A nagging feeling about an area, a mark or spill will arise. If that feeling persists over a period of time, it will become clear that the area needs re-working. Circumstances where one small thing will be altered causing a domino affect in which many other things will need to be re-adjusted. When the space to form ratio is in balance or perfectly off balance, I will stop working the piece. Letting it rest for three days, I will come back to it with fresh eyes to see if it resonates as finished. The final question I have to ask myself is whether the piece functions best with its subjective flaws.

A balance of the organic nature of paint and the deliberate placement of forms with paint is something I strive for. Premeditating and with great labor over depiction my previous forms were rendered. Now they are less namable and evolve out of the process, coming about in a much more veritable way. Still reminiscent of subjects I have drawn before, the forms possess more mystery and in turn more truth while referencing stored memories. The first of the gold fringe-frame pieces is titled Sweet pea (1. Sweet pea, mixed media with imitation gold leaf, 69″ x 50.5”, 2012.). The forms within echo the shape of the flower and also the color. Sweet peas have always been in my life, from childhood in my mother’s acre large garden. With the beauty of the flowers form and the complex deterioration of paint layers flaking away with shellac moving across the surface a metaphor of our relationship is painted. The marrying of beauty and decay is constant in my work. Forms are sown and simultaneously rot, into and out of the paint surface.

A balance of the organic nature of paint and the deliberate placement of forms with paint is something I strive for. Premeditating and with great labor over depiction my previous forms were rendered. Now they are less namable and evolve out of the process, coming about in a much more veritable way. Still reminiscent of subjects I have drawn before, the forms possess more mystery and in turn more truth while referencing stored memories. The first of the gold fringe-frame pieces is titled Sweet pea (1. Sweet pea, mixed media with imitation gold leaf, 69″ x 50.5”, 2012.). The forms within echo the shape of the flower and also the color. Sweet peas have always been in my life, from childhood in my mother’s acre large garden. With the beauty of the flowers form and the complex deterioration of paint layers flaking away with shellac moving across the surface a metaphor of our relationship is painted. The marrying of beauty and decay is constant in my work. Forms are sown and simultaneously rot, into and out of the paint surface.

One more step removed from representation, are the forms I make using shellac. It has a loose quality and after much experimentation, is predictable.The material represents a simultaneous sense of repulsion and attraction to witnessing life cycles along with decomposition. Representing visceral substances and textures is my attempt at expressing my celebratory curiosity for the inner workings of life. A story is held behind the iodine spill that took place in the horse stall, and the events, which lead to hard balls of tar in our kiddy pool on a hot summer day. Many of these forms are abstracted memories that have become engrained in my mind, all spawning from a subconscious motto to keep open eyes, to look and to be curious.

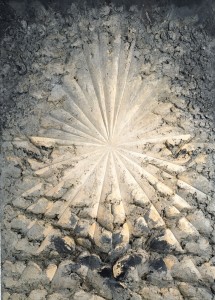

The figure/ground relationship between forms and space is why I have forms at all. Making things stand apart from each other and coaxing forms to push and pull spatially, is very important to the paintings overall integrity. Compressing my experience into a flat canvas comes directly from a rhythm that occurs. While outside I look at the ground, I look at the distance, then at the sky. Looking back at the ground, I remember I am en route. Finding my path again I look up at the distance, the sky, the weather and the clouds. Avoiding a fall I look for things I may step on; snakes, rocks, holes and thorns. There is a real pattern to it, and the same goes while on a horseback. Visual snags, like sun-bleached bones that pop out from the ground, or sage partially covered in asphalt by the side of the road are the type of figure ground relationships I watch for. They are areas where things are touching and in direct contact with one another, either delicately or with some sort of violence. Cardio (2. Cardio, mixed media with imitation gold leaf, 69″ x 50.5”, 2012.). is a declaration of this sort of moment, incorporating an aggressive rhythm with a delicate balance of natural order and visual information.

The figure/ground relationship between forms and space is why I have forms at all. Making things stand apart from each other and coaxing forms to push and pull spatially, is very important to the paintings overall integrity. Compressing my experience into a flat canvas comes directly from a rhythm that occurs. While outside I look at the ground, I look at the distance, then at the sky. Looking back at the ground, I remember I am en route. Finding my path again I look up at the distance, the sky, the weather and the clouds. Avoiding a fall I look for things I may step on; snakes, rocks, holes and thorns. There is a real pattern to it, and the same goes while on a horseback. Visual snags, like sun-bleached bones that pop out from the ground, or sage partially covered in asphalt by the side of the road are the type of figure ground relationships I watch for. They are areas where things are touching and in direct contact with one another, either delicately or with some sort of violence. Cardio (2. Cardio, mixed media with imitation gold leaf, 69″ x 50.5”, 2012.). is a declaration of this sort of moment, incorporating an aggressive rhythm with a delicate balance of natural order and visual information.

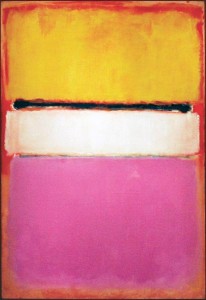

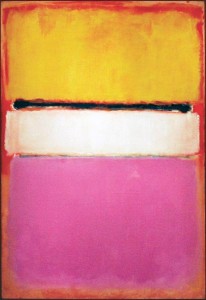

Having had no real knowledge of contemporary art until attending The University of Montana in 2007, I must have been very confused. My training up to that point was mostly classical, from observation and heavy on the idea of drawing directly from life. Living in Wyoming and having a basic survey of art history that lead up to the Abstract Expressionists movement, I did know who Jackson Pollock was. Taking an abstract process class while earning my bachelor of fine arts degree was a huge turning point for my work and to discovering what art appeals to me. Since then I have discovered these basic things about how art needs to function for me: if the initial thing that strikes you is a feeling than the art is functioning. After finding out what the artist’s intention were, and still you feel your own gut reaction then the art is good allows for interpretation. Art should always possess beauty (which is subjective) and intention. I choose to be a painter and love to look at paintings because there is so much of the individual’s physical presence in the object of the work. After sitting in front of a Mark Rothko (3. Mark Rothko, White Center, 1950.) painting I always feel awe for what paint can do, how it can be so mysterious and seem to be breathing. All forms of painting interest me, but some works more than others transfix.

Having had no real knowledge of contemporary art until attending The University of Montana in 2007, I must have been very confused. My training up to that point was mostly classical, from observation and heavy on the idea of drawing directly from life. Living in Wyoming and having a basic survey of art history that lead up to the Abstract Expressionists movement, I did know who Jackson Pollock was. Taking an abstract process class while earning my bachelor of fine arts degree was a huge turning point for my work and to discovering what art appeals to me. Since then I have discovered these basic things about how art needs to function for me: if the initial thing that strikes you is a feeling than the art is functioning. After finding out what the artist’s intention were, and still you feel your own gut reaction then the art is good allows for interpretation. Art should always possess beauty (which is subjective) and intention. I choose to be a painter and love to look at paintings because there is so much of the individual’s physical presence in the object of the work. After sitting in front of a Mark Rothko (3. Mark Rothko, White Center, 1950.) painting I always feel awe for what paint can do, how it can be so mysterious and seem to be breathing. All forms of painting interest me, but some works more than others transfix.

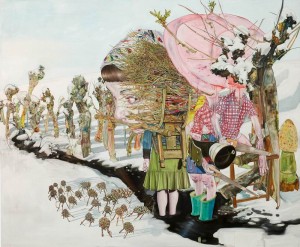

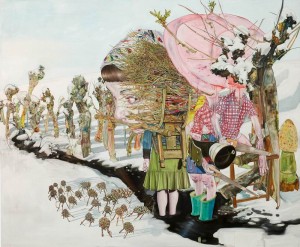

The body forms of Leopold Rabus (4. Leopold Rabus, The shepherd and the lumberjack, 2006.), while seemingly disconnected with mine, evoked such a powerful initial connection for me that I bought a book on multiple artists just to study him. His figures are all very distorted and mangled up in transformation; something physical is happening to the body. The context of his work is obviously rural. His subjects are all dressed in a site-specific kind of way, very insular and sort of backwards. Sometimes there are animals involved and always an element of nature to help build his incredibly complex compositions. The natural aspects of his work, the environments, colors, and circumstance he uses, are all underlying motivators in my process. Rabus uses his knowledge of paint and ability to render, to create action and new forms while deliberately confusing the space. Always there are elements to the work that repulse and captivate.

The body forms of Leopold Rabus (4. Leopold Rabus, The shepherd and the lumberjack, 2006.), while seemingly disconnected with mine, evoked such a powerful initial connection for me that I bought a book on multiple artists just to study him. His figures are all very distorted and mangled up in transformation; something physical is happening to the body. The context of his work is obviously rural. His subjects are all dressed in a site-specific kind of way, very insular and sort of backwards. Sometimes there are animals involved and always an element of nature to help build his incredibly complex compositions. The natural aspects of his work, the environments, colors, and circumstance he uses, are all underlying motivators in my process. Rabus uses his knowledge of paint and ability to render, to create action and new forms while deliberately confusing the space. Always there are elements to the work that repulse and captivate.

The work of Fiona Rae (5. Fiona Ray, Untitled (yellow with circles I), 2001.) is more removed from recognizable imagery and relates on many levels to my work and process. Her manipulation of paint properties, how she edits and allows that process to be part of the finished piece in tandem with conscious placement of forms, are all things I employ in my process. This type of process allows room for chance and the trajectory of thought is evident. Works by Fiona that are of particular interest and embody this process are; Untitled (yellow with circles I), and Untitled (Orange and Turquois). These paintings, like mine, contain frenetic energy with moments of contemplative space.

The work of Fiona Rae (5. Fiona Ray, Untitled (yellow with circles I), 2001.) is more removed from recognizable imagery and relates on many levels to my work and process. Her manipulation of paint properties, how she edits and allows that process to be part of the finished piece in tandem with conscious placement of forms, are all things I employ in my process. This type of process allows room for chance and the trajectory of thought is evident. Works by Fiona that are of particular interest and embody this process are; Untitled (yellow with circles I), and Untitled (Orange and Turquois). These paintings, like mine, contain frenetic energy with moments of contemplative space.

David Reeds (6. David Reed, #482, 2002.) paintings are much like those of Rae, but with a stronger figure/ground relationship. Loose applications of paint made over clean flat bars of color are the predominant elements. These two opposites sit on the surface of the canvas in static conflict. Moments of unease and gestures that gracefully transition into the very structural space of flatness, creating instances of beauty in an uncomfortable environment are much like the spaces I created in Sweet pea.

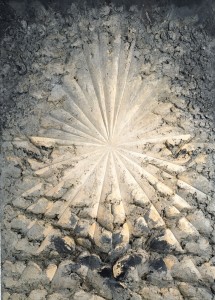

Paintings that exhibit great physicality with a demanding presence are what I make. Jay DeFeo’s, The Rose, (7. Jay Defeo, The Rose, 1958-66.) which ended up weighing nearly one thousand pounds, is a good example of the addiction to how physical work manifests in painting. Works less epic in scale but still possessing similar qualities are those by Anselm Kiefer. Kiefer’s burly paintings look and feel like a field covered in mud and hay. The weight and the three-dimensionality of paintings by DeFeo and Kiefer are qualities present in my work. The fringe-frames oppose the rigid structure of the stretchers bars underneath and garnet gel crusted in shellac protrudes from the surface of the canvas.

Paintings that exhibit great physicality with a demanding presence are what I make. Jay DeFeo’s, The Rose, (7. Jay Defeo, The Rose, 1958-66.) which ended up weighing nearly one thousand pounds, is a good example of the addiction to how physical work manifests in painting. Works less epic in scale but still possessing similar qualities are those by Anselm Kiefer. Kiefer’s burly paintings look and feel like a field covered in mud and hay. The weight and the three-dimensionality of paintings by DeFeo and Kiefer are qualities present in my work. The fringe-frames oppose the rigid structure of the stretchers bars underneath and garnet gel crusted in shellac protrudes from the surface of the canvas.

The direct and aggressive stabbing and cutting of Lucio Fontana’s canvases conjure up images of the artist’s actions. Joan Mitchell’s paintings (8. Joan Mitchell, untitled, 1992.) nearly double her height and reveal large arm span brushstrokes. The object of a painting in relation to the body is important and affords the viewer hints and clues about it’s making. Scale and the movement of the paintings that exist within my tediously gold leafed fringe-frames are my way of utilizing physical touch and repetition.

The direct and aggressive stabbing and cutting of Lucio Fontana’s canvases conjure up images of the artist’s actions. Joan Mitchell’s paintings (8. Joan Mitchell, untitled, 1992.) nearly double her height and reveal large arm span brushstrokes. The object of a painting in relation to the body is important and affords the viewer hints and clues about it’s making. Scale and the movement of the paintings that exist within my tediously gold leafed fringe-frames are my way of utilizing physical touch and repetition.

Processing life through the addiction of work, I paint. My relationship with the paintings is like a mirror, helping me to see myself. Learning about my personal tendencies and trusting my initial gut reaction is my most valued lesson. Allowing my physical actions to lead me to deeper meaning is the essence of what I do. The beauty I find in decay, my habitual ground searches and the need for tactility are all qualities that have been inherited from my upbringing and now manifest themselves through the images I make. Continually finding new places to work and be fed as an artist, I gain new perspective. In my mind’s eye I see work that moves off their frames and traverse across the wall. Mixed media is in store with the solid grounding of being paintings.

Connective tissue: The 2016 Olympic Games in Rio, Brazil were just beginning at the same time I found myself at this exhibition. They are just ending as this post finds its way into the world, so there will be a new set of issues for commentators and those who comment on the commentators. At this moment, however—when I was standing in front of a Krasner painting titled “What Beast Must I Adore?” (from a Rimbaud poem)—backlash against newscasters’ handling of the gender politics connected to reportage of women athletes was what was getting headlines. The Chicago Tribune had just reported the accomplishment of Corey Cogdell-Unrein (trap shooting) with the tag “Wife of Bears’ Lineman Wins a Bronze Medal Today in Rio Olympics.” They didn’t bother with her name. Elsewhere, NBC’s Dan Hicks expounded for quite a while after a world-record swim by Katinka Hosszu on her husband who, apparently, was “responsible” for the feat.

Connective tissue: The 2016 Olympic Games in Rio, Brazil were just beginning at the same time I found myself at this exhibition. They are just ending as this post finds its way into the world, so there will be a new set of issues for commentators and those who comment on the commentators. At this moment, however—when I was standing in front of a Krasner painting titled “What Beast Must I Adore?” (from a Rimbaud poem)—backlash against newscasters’ handling of the gender politics connected to reportage of women athletes was what was getting headlines. The Chicago Tribune had just reported the accomplishment of Corey Cogdell-Unrein (trap shooting) with the tag “Wife of Bears’ Lineman Wins a Bronze Medal Today in Rio Olympics.” They didn’t bother with her name. Elsewhere, NBC’s Dan Hicks expounded for quite a while after a world-record swim by Katinka Hosszu on her husband who, apparently, was “responsible” for the feat.