About a month ago, before any of the awards were given out, my wife and I went with our 14 year old son to see Whiplash, one of the Best Picture nominees for 2014. We went partly because the movie was getting critical praise, but mostly because our son, who is strongly considering a career in music, really wanted to see it. After watching the movie I found it unusually hard to characterize my feelings about it. Was it a “great movie,” as some of my writing students were emphatically declaring the other day? Well, yes, I guess it does rank as that. Certainly it is well-filmed and well-acted—J. K. Simmons without question deserved the Oscar he won for his performance as Terrence Fletcher, the insanely aggressive teacher—and I know it affected me more than any other movie I’ve seen in recent memory. In fact, Whiplash absolutely hit me in the gut. But here’s the thing: The effect it had on my gut is that it made me sick.

I found the movie very hard to watch even if it is brilliantly put together, and even if the young protagonist, Andrew Neiman, is a very sympathetic character. But let me clarify, it wasn’t hard to watch because of the way the Fletcher psychologically and even physically abuses Andrew. As a teacher of creatively ambitious students, I despise and reject every single teaching “method”–if one can call them that–that Fletcher espouses. But it’s not his methods that made me sick. What made me sick is that the movie endorses them. Early on, sensing where it was going, I turned to my wife and whispered something to the effect of “I hope they’re not saying this is okay.” I watched on, waiting and hoping for the “not okay” message that never came. No, what came was the exact opposite, which is why to my students’ announcement that Whiplash is a “great movie” I finally replied: “It may be a great movie, but it’s not a good one.” Because a good movie does not make you leave the theatre revolted and heartsick, with disgusting and dangerous notions echoing through your brain.

I found the movie very hard to watch even if it is brilliantly put together, and even if the young protagonist, Andrew Neiman, is a very sympathetic character. But let me clarify, it wasn’t hard to watch because of the way the Fletcher psychologically and even physically abuses Andrew. As a teacher of creatively ambitious students, I despise and reject every single teaching “method”–if one can call them that–that Fletcher espouses. But it’s not his methods that made me sick. What made me sick is that the movie endorses them. Early on, sensing where it was going, I turned to my wife and whispered something to the effect of “I hope they’re not saying this is okay.” I watched on, waiting and hoping for the “not okay” message that never came. No, what came was the exact opposite, which is why to my students’ announcement that Whiplash is a “great movie” I finally replied: “It may be a great movie, but it’s not a good one.” Because a good movie does not make you leave the theatre revolted and heartsick, with disgusting and dangerous notions echoing through your brain.

For those who haven’t seen Whiplash and don’t intend to, here’s a quick summary. Feel free to skip ahead if you already know the movie. Andrew Neiman, a talented, hard-working, and, most of all, ambitious young jazz drummer enters the prestigious Schaffer Music Academy in New York. Andrew is soon noticed by Fletcher, who promotes him to the “A team,” so to speak; that is, Fletcher’s orchestra. Fletcher’s teaching methods amount to psychological torture and physical demands that border on the lunatic. He literally makes Andrew bleed, but even worse are the constant mind games he plays, as he pits students against each other, lies to them, and consciously undervalues them. His great mantra is that Charlie Parker only became Bird because somebody threw a cymbal at his head. It’s a long story, but Andrew is finally cut from Fletcher’s orchestra and expelled from the school—but not because he isn’t a good player. He reluctantly agrees to participate (on an anonymous basis) in a lawsuit against Fletcher, the result being that Fletcher is fired from Schaffer.

Later, Andrew discovers that Fletcher is playing in a neighborhood jazz bar, and he stops in to listen. Fletcher sees Andrew afterwards and they have a come-to-Jesus meeting in which Andrew seems to abandon all his former reservations about the teacher. Fletcher, in turn, asks Andrew to play drums in an orchestra he has put together for a festival gig at Carnegie Hall. It’s Andrew’s big chance to return, and to be noticed—in a big way! But as it turns out, the request is a set-up. Fletcher—who, it turns out, knew all along that it was Andrew who brought the lawsuit against him—doesn’t inform Andrew about the new song he intends to open the first set with, and Fletcher doesn’t provide him with the sheet music. Andrew tries to fake it but fails miserably. It looks like it’s all over for him. He walks off stage humiliated. But then, rather than quit, he walks back on stage and starts drumming out the opening of “Caravan,” forcing the orchestra and Fletcher to follow along, as if this is planned. Long story short, Andrew gives the drumming performance of his life, including a ridiculously elongated solo. At the very end of the movie, he and Fletcher smile at each other, as if this level of accomplishment is what the teacher had wanted all along, planned for all along, and finally got.

Some disagree about the meaning of that last crucial scene, but it seems pretty clear to me that no matter what Fletcher really intended to have happened, he comes out smelling like a rose. Either his former student, the one who brought a lawsuit against him, would leave thoroughly humiliated by the teacher’s crafty if evil power play—proving that you never mess with the man—or the former student would use the humiliation to come back at him and prove to be Fletcher’s greatest accomplishment as a teacher. Fletcher would have found and formed the next Bird, so to speak. (I know, I know. Bird was not a drummer.) Either way, Fletcher wins. He earns respect. And that’s what really bothers me about the movie. Not only does it not do away with Terrence Fletcher, it winds up endorsing his many misguided and clichéd notions about the art of teaching.

As others commenting on this movie have made clear, there’s no way anyone as openly abusive as Fletcher would be allowed to teach in the first place. You won’t find teachers like him in music schools if only for the fact that the students at those schools are paying ungodly amounts to go there—and not for the sake of being abused. But that’s really beside the point for me. Whether a Terrence Fletcher actually exists is immaterial. What matters is that teachers like him exist in the public’s imagination, and I fear—in fact, I know—that they are romanticized to the point that bad teaching practices become operative cultural myths.

What myths and practices am I talking about? First, the idea, openly embraced by Fletcher, that everything he does as a teacher is for the sake of that one gifted student. He breezily dismisses any and all concern for the rest of his charges. Problem is, all of his students pay tuition. So a teacher who really is one tries to educate them all. It’s called teaching. You try to help all of them, understanding that of course in the end they will each reach different levels of achievement. Because that’s your job. Second, how can Terrence Fletcher, before he decides which particular student should be the focus of his psychopathic attentions, be so sure which student is the one and which isn’t? I had a teacher in grad school who claimed he could tell if you were a poet or not after reading only three lines. Three lines? This is so stupid a claim (and I knew it was stupid then) I don’t even know where to begin. Human beings develop at remarkably different rates. Some shine out loud when they are very young; some shine only a little but shine more and more the older they get. Some shine brightly, but then are too distracted or too lazy or too unfortunate to ever shine any better. Some shine bright for a minute and then burn out. Some shine brightly and only get brighter as they age (e.g., W.B. Yeats). No one can or should make absolute statements about any person’s talent based on one point in that person’s working career. And besides, poems are as different as they come. I don’t mean from poet to poet but within the work of a single poet, even during the same period of her writing life. Three lines of one poem is so paltry a sample of a person’s work it’s laughable. To claim you can judge a poet after three lines—or a musician after three seconds (as Fletcher does repeatedly in the movie)—is to prove oneself ignorant of both human nature and the arts.

An even bigger problem with the myth is that even for the gifted student, Fletcher’s methods are not only not productive; they are counterproductive. No one realizes his inner potential by being ridiculed and humiliated and insulted. That is one of the most toxic, and most enduring, misconceptions of the teaching profession. What happens when someone is ridiculed and insulted is that they are driven away. They are shut down. They become afraid. No one who is afraid ever makes great art. No one who is afraid ever actualizes anything. Don’t get me wrong. I’m not of the school that says you should only praise students. I don’t think any student of mine has ever written something that could not be improved and that I haven’t said as much to them. But at the same time, constructive criticism can and should be delivered without insulting and dismissing the writer of the words. Without claiming that they shouldn’t even try. That’s what you should never do. Because you don’t have the right to. And because there are simply too many cases where teachers who say such things wind up being wrong and looking foolish.

I’m not sure if it’s widely understood just how much of a myth the myth of the bastard teacher is. Far from guaranteeing that the great artists come, there’s no telling how many great artists have been stymied and blunted by the arrogant slash-and-burn school of instruction. Unfortunately, there are people in the world—like the writers of Whiplash—who believe that intimidation, maligning, and mind games really do work as teaching tools. In fact, I’m willing to bet that in the general population there are a higher percentage who believe that this is how “real” artists are shaped than who know better. I can swear to you that there are many people in the world who believe that a teacher of writing should just tell some of her students to give up. (Just ask my wife how many of her Teaching Creative Writing students have asked her exactly when they are supposed to tell a young student this. The ironic thing is that these people are almost never good writers themselves.) The charismatic teacher who dominates his room like an old school general may be cinematic, but he’s really of no use to anyone or anything except his own ego. Actual teachers know that there is no one-note system guaranteed to reach all your students or even all your best students. Every single student learns a little differently and that makes broadly effective teaching an amazingly complex and multi-dimensional endeavor, one that requires knowledge and smarts and confidence, but even more intuition and mind-reading, acute sensitivity and the ability on rare occasions to turn off that sensitivity; good humor, an infinite amount of patience, as well as the ability to become impatient once in a while. See, it really is a ridiculously complicated task. But that’s no fun for screenwriters. You can’t make an unforgettable and cinematic a**hole out of complication, intuition, and patience.

But you can get J.K. Simmons an Oscar. And you can get a lot of college students talking.

[Note: This is an updated version of a post that originally appeared on Vanderslice’s own blog Payperazzi.]

Visit John’s website here and his blog here

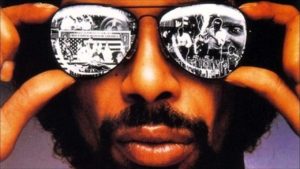

This month’s JAZZ meets POETRY event is a Tribute to Gil Scott-Heron, and will be held at The Nash (110 E Roosevelt St, Phoenix, Arizona 85004) on April 26 from 7:00-10:00 pm.

This month’s JAZZ meets POETRY event is a Tribute to Gil Scott-Heron, and will be held at The Nash (110 E Roosevelt St, Phoenix, Arizona 85004) on April 26 from 7:00-10:00 pm.