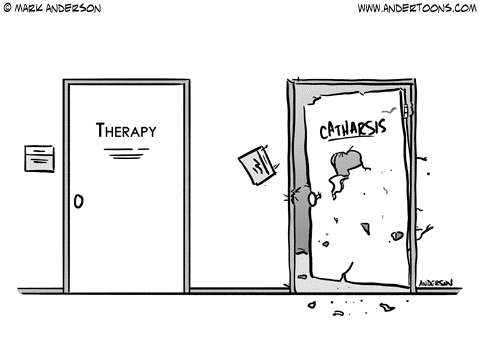

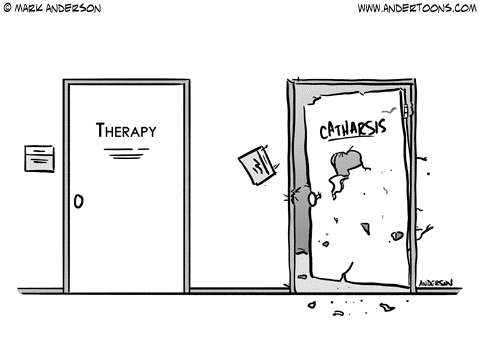

The Process: Catharsis, Counseling, and Creative Writing

When talking about writing in literary crowds, I skirted away from using the word, “catharsis.” In an attempt to mask my youthful unknowingness—and to hopefully step into the realm of literariness (as if it were The Thing to attain)—I distinguished my stories as maturely lacking any cathartic-make-you-feel-better qualities. What an insecure snob I was!

With help, I have reworked this naïve snobbery into quality-mongering [meaning: verb: an attempt to look for quality; to go above and beyond; to go deeper; to refine; to grow; noun: quality mongers: those who practice quality mongering]. Can quality-mongering be petty? Sometimes. Is it honest? Always.

Writing short stories, for me, has included a constant flow of quality mongering. A constant reshaping and refining of something too raw. For some emotionally bloody and raw story starts, I would overcook and sterilize any cathartic, tender aspects of me that may still be on the page. I struggled with the thought of me entering the story. A writing no-no. I hadn’t considered my own self-protection also taking place.

Writing short stories involves creating mini realities—mini snapshots into a moment or a series of moments. In my own writing process, crafting a reality often derived from a source within me; a few friends can trace the crumbs of Jess scattered on the page and across my reoccurring themes. While trying to excise “me” out of the story, I would tell myself that I was inhabiting the world of another, writing outside of “what I knew,” and seeking quality by using structured writing. I insisted that any catharsis I experienced while writing never remained in the pieces I considered my art.

I wasn’t exactly wrong; I wasn’t exactly right.

After some growing up a bit and reworking my constructs about writing, I encountered this concept of catharsis and artistic healing increasingly. Now pursuing a career in mental health counseling, I can’t help but use my reader/writer brain to connect the dots between client stories and counseling processes—including catharsis.

Catharsis followed me everywhere. As a volunteer creative writing teacher at a prison, I encountered the question of writing from hurt on my first day teaching a writing class.

Catharsis followed me everywhere. As a volunteer creative writing teacher at a prison, I encountered the question of writing from hurt on my first day teaching a writing class.

I recall asking each of the orange-clad men sitting around me, “What do you want to learn in this class?”

In the small classroom, which looked like one of those WWII Quonset huts, I received an assortment of answers:

- “To write good.”

- “To write better.”

- “To write home.”

- “To write past the writer’s block.”

One student then said, “I want to know how to write, but like, write without it hurting too much. I think sometimes, if I write, it will just all come out and be too much. Hurt too much.”

There had been a collective nod—and sigh—as if we were all waiting for the air conditioning to turn on, to greet us, to remind us that we weren’t in a prison.

Hurt too much. What about writing for catharsis? I questioned my subjectivity, which I lumbered around while trying to hide it—could my own insistence to not use catharsis also stem from a fear of hurting? Was it about pain or about image? About art? About refining?

My writing and counseling worlds collided, and consideration of my student’s question was necessary.

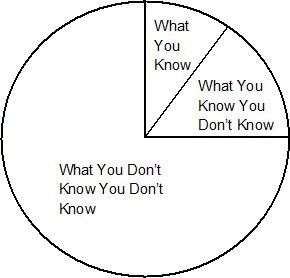

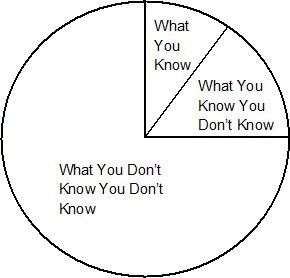

Within my first few weeks of learning counseling theories and techniques, I easily adhered to the word, “phenomenological,” and the concept of the subjective reality in which each of us operates in the world. Our internal framework. Each person perceives their Truth from a separate, conscious mind. Writers and readers momentarily occupy the minds of others. But even stories are clipped snapshots of a phenomenological reality. Salience-focused movie-reel slides. Refined and revised to show a subjective experience.

After doing a mock therapy session, I noticed more parallels between writing and therapy: themes and patterns, language-fixation, subjective realities; meaning and feeling; images and metaphors.

As a counselor, though, I am no longer writer but rather reader of these salience-focused, sometimes refined/rehearsed, sometimes unfiltered/uncensored, mini-snapshots into clients’ phenomenological worlds. Their experiences. Their internal frameworks. While I can never fully inhabit each client’s consciousness and understand every nuance of their being, I can piecemeal their themed stories to better understand—to better connect with our shared humanity.

Woo woo? I sure hope so.

In counseling, there are various change processes applied to differing theoretical approaches including consciousness raising, choosing, catharsis, contingency control, and conditioned stimuli.

Often, therapy involves raising the awareness of those seeking help. Often, therapy involves choice—sometimes outside of decision. Often, therapy involves pairing stimuli. Often, therapy involves behavior/thought management.

Often—therapy involves catharsis.

Even within some counseling circles, the use of catharsis can elicit that same negative connotation I had applied with writing. Is it bad to write from a source of emotion? Of pain? Is it inferior to use a healing process based in releasing repressed emotions? Is it inferior to find relief? Is it unrefined and unsophisticated to write with catharsis? Is there valence at all?

Am I asking the right questions?

Then there’s my student’s question. How do you write without it hurting too much?

Should it not hurt? Hurt. Hurt. Hurt.

The healing process—whether attributed to counseling change processes, writing processes, reading processes, revision processes, whatever process—appears to be just that: a process.

Could we quality mongers be searching for The Thing when we should be along for the active, growing journey? Is my subjectivity showing?

Could we quality mongers be searching for The Thing when we should be along for the active, growing journey? Is my subjectivity showing?

This realization—that maybe there is more than a black and white answer—showed me how truly youthfully unknowing I had been. And that was okay. In class, I have learned, that “you don’t know what you don’t know, until you know.”

With writing—and with healing—sometimes the consciousness raising and choosing occur alongside the cathartic journey, which includes sometimes pain and sometimes relief and sometimes emotion and sometimes ugly, messy beginnings. Shitty first drafts.

For me, writing derives from a self-actualizing delight in understanding another human’s phenomenological world, in rewriting my own, and in recognizing the holistic nuances of being human.

The Process no longer appears linear. Rather, aspects of catharsis may occur in all stages of writing, revising, and editing. Consciousness raising continually occurs—and thank goodness it does—and my thoughts, behaviors, and values continue to interplay within my counseling, my writing, and my way of being.

Slightly more aware, slightly less insecure, slightly less snobbish, slightly more honest, I see less fog in actively writing with sometimes cathartic beginnings and processes. I see the ways in which no three-pronged thesis could possibly support the dynamic writing and revision process and its human component.

There may be no perfect and mature answer to my student’s question. My awareness may only be raised slightly. This could be messy. But damn, it feels good.

—

The term, “Quality-Mongering,” can be credited to Christopher Greene.

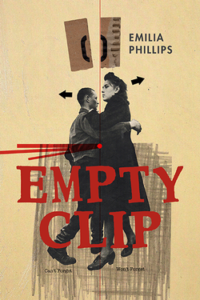

Today we are pleased to share news about past contributor Emilia Phillips. Empty Clip, Phillips’ third poetry collection, will be released by University of Akron Press on April 23, 2018. The collection deals with the cultures of violence in the United States and the effect they have on female body image and mental health. Empty Clip is available for preorder from University of Akron Press

Today we are pleased to share news about past contributor Emilia Phillips. Empty Clip, Phillips’ third poetry collection, will be released by University of Akron Press on April 23, 2018. The collection deals with the cultures of violence in the United States and the effect they have on female body image and mental health. Empty Clip is available for preorder from University of Akron Press