Lately I find myself less intimidated by the blank page (screen), and more by the thought of revising something I’ve already written. Not something in the early stages—usually when I’ve got a new project underway, I can’t wait to get back to it. The revisions I dread—or at least postpone far longer than I should—are on work I’ve already sent out into the world, one way or another. Writing I’ve workshopped at a conference, with feedback that now must be weighed. Writing I’ve submitted to literary journals that has been rejected often enough—even if some rejections have been encouraging—that I know I must reopen the file, reread my own work and wrestle with my pages.

Of course the ease with which we make revisions these days—and here I am talking about the mechanical ease of editing a document through the magic of word-processing software, not the mental work that goes into rewriting—is something most of us take for granted. But it hasn’t always been that way. I used a manual typewriter—and gallons of whiteout—in high school. I pecked my way through college papers on an electric typewriter, which fortunately had a ribbon of corrective tape, because I’ve always been a lousy typist. My first job after college was as a medical writer in a teaching hospital, where I worked with staff physicians and visiting fellows and residents to polish their research papers, book chapters and presentations. We were lucky enough to have in our office one of the three word-processing machines in the hospital; it was about the size of a Mini Cooper, and only two people in our four-person department were even allowed to touch it. I wasn’t one of them—my job was to write on or mark up paper, sometimes to literally cut and paste (with scissors and tape), then turn the pages over to one of the girls whose job it was to type or revise documents. In the 1980s, this was cutting-edge technology. Our machine was a Vydec, and he (we four women all agreed the big lug was a “he”) was both a technological wonder and a highly temperamental co-worker. At least once a week, Vydec acted up and we had to call in a technician. Still, we cranked out a lot of medical papers on that old machine, and the doctors were not at all shy about asking for one more set of revisions before we sent their pages out into the world. They took to word processing like ducks to water.

With one exception—Tiger John, a surgeon from China who spent about three years with us as an international fellow. He was one of the first physicians permitted to leave China after the Cultural Revolution, and he was in the U.S. to learn about Western medicine so he could bring new knowledge back home. He couldn’t practice here, but he could watch surgeries, observe clinics, attend conferences. And since everyone around him was writing papers, he thought he’d try that, too.

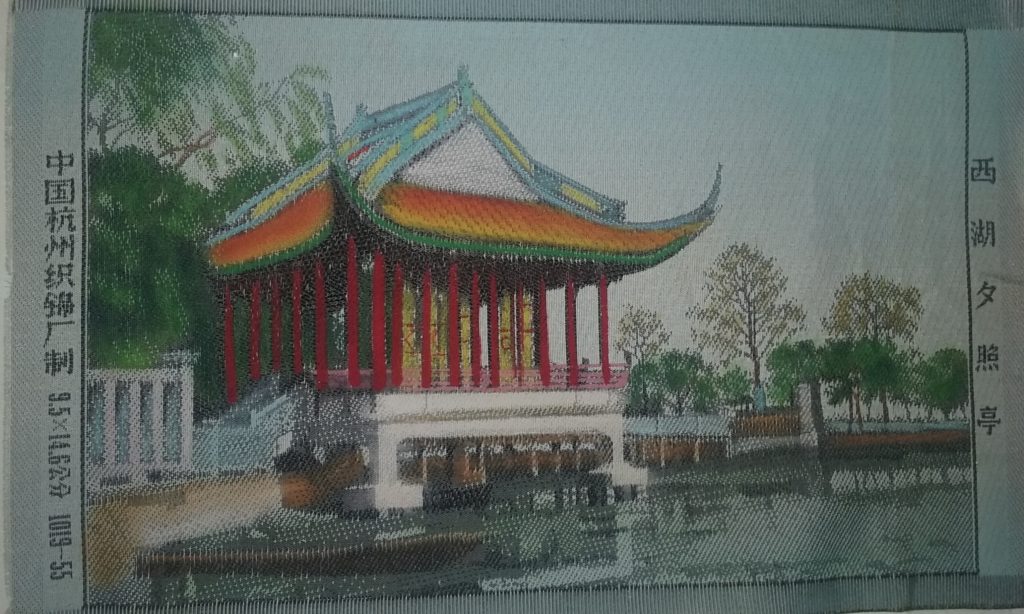

Everyone loved Tiger, who was nothing like his name. He was gentle and polite. And he was constantly offering us small gifts from China. I’ve kept one of Tiger’s gifts for nearly 35 years, because in itself it is a treasure, but also because it holds a riddle it took me forever to solve. It’s a small rectangle of silk, printed with the image of a large marble boat. Tiger explained it was a real boat, made of marble, from a long time ago. But with his limited English (and my nonexistent Mandarin), he couldn’t make me understand how a marble boat could float. It was a marvel, for sure. But our conversation about it ended as many of our conversations did—with me nodding my head, him bowing, and both of us grinning, pretending we’d managed to communicate more than we actually had.

Everyone loved Tiger, who was nothing like his name. He was gentle and polite. And he was constantly offering us small gifts from China. I’ve kept one of Tiger’s gifts for nearly 35 years, because in itself it is a treasure, but also because it holds a riddle it took me forever to solve. It’s a small rectangle of silk, printed with the image of a large marble boat. Tiger explained it was a real boat, made of marble, from a long time ago. But with his limited English (and my nonexistent Mandarin), he couldn’t make me understand how a marble boat could float. It was a marvel, for sure. But our conversation about it ended as many of our conversations did—with me nodding my head, him bowing, and both of us grinning, pretending we’d managed to communicate more than we actually had.

Lately, I’ve been feeling like making myself sit down to start a revision is like trying to make a marble boat float: impossible. The longer I wait, the more I convince myself I’ll be disappointed with my writing—and, because mostly I write personal essays—with my life.

Revision always reminds me of Tiger John—although not in the best way. Tiger took to word processing like a marble boat takes to water. He used a manual typewriter, and when he was satisfied with a draft, he would bring it to me, as if it were another of his gifts. His typing was worse than mine, and with little English at his command, his manuscripts were incomprehensible. I’d read through his pages, making edits and scribbling questions in the margins, drawing arrows to indicate which paragraphs might be moved where. We’d discuss—as best we could—what I had understood and what he had intended. Then I’d mark up the pages some more, and turn them over to one of my colleagues, who would sit down with Vydec and produce an almost-readable manuscript. Which I would proof, she would re-revise, and together we would present to Tiger—as if it were our gift to him.

Tiger, it seemed, had as much trouble grasping the concept of a word processor as I had with the concept of a marble boat. He just couldn’t make it float in his head. And so every time we gave him a neat new manuscript to review—and even after we’d let him stand near Vydec and watch as words were typed and came up on the screen and as pages with those very words were spit out of the printer—he’d go all the way back to the drawing board and spend days mistyping his next revision. Which he would deliver to me, smiling broadly. And we’d start all over again. If any of those papers ever got published, it was after he returned to China, and probably in his own language.

I’ve kept the little piece of silk with the marble boat—in a plain white ceramic frame—near at hand for all the years since I knew Tiger John. It’s a reminder of people I met in that hospital half a lifetime ago, people from across the country and around the globe. It’s also been a reminder that what seems impossible often can be done—I mean, if ancient Chinese engineers could figure out how to make a marble boat float, anything is possible, right?

Except that’s not exactly what happened. Not long ago while cleaning up my home office (a highly effective tactic for avoiding the work of revision), I dusted the frame around my silk marble boat and thought to myself, I should Google that. And I did, and discovered that while there is indeed such a structure on the grounds of the Summer Palace in Beijing, originally built in 1755, it is a lakeside pavilion shaped like a boat, not a vessel that was ever meant to float. The Marble Boat is sometimes called the Boat of Purity and Ease, which is what one can only aspire to when it comes to writing—and revision.

So lately, I’ve been thinking about the marble boat in a whole new way. I’ve been using it as a reminder that Tiger John made revision so much harder than it had to be. Like I do, but in a different way. Because when I do finally get around to rereading myself, I almost always find some things to like about what I’ve written, even when I also see ways it could be improved. And so I sit with my pages and start marking them up, and eventually I head for my computer, open the file, and begin revising in earnest. Perhaps not with purity and ease, but with every intention of making the work better, making it sing, maybe even making it sail.