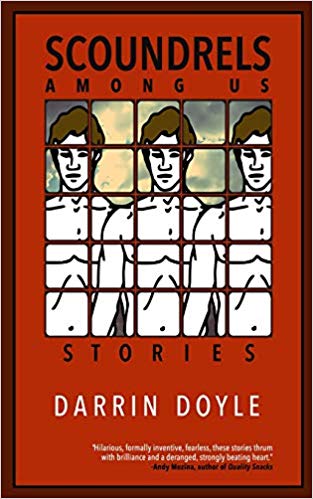

Spoiler alert: My new story collection Scoundrels Among Us isn’t going to win the National Book Award. It’s not even going to be nominated. It’s not going to take home the Pulitzer Prize or the Pen/Faulkner Award, either. None of those accolades will be mine.

But am I crying? Heck no! I’m not bitter because truthfully, the deck is stacked against me. I never had a shot in the first place. And I’m not alone, either. Thousands of terrific writers aren’t going to win these prizes – not because they’re bad or inferior to those nominees but because of the kind of books they write. Plain and simple, these writers are: Just. Too. Funny.

Perhaps you’ve noticed that what our culture deems Great Art is typically synonymous with Serious Art – subjects containing gravity, tragedy, emotional heft. The story must deal with dramatic circumstances, and with a straight face. War. Divorce. Poverty. Oppression. Think Grapes of Wrath and A Farewell to Arms. Think To the Lighthouse and Beloved. (All amazing books, by the way!)

To make the audience laugh, to spin yarns of absurdity, parody, satire, or – Heaven forbid – slapstick is akin to the artist not wrestling meaningfully with anxiety, trauma, sadness, anger, or pain. This is what our culture implies, anyway, through its judgement. Just look at the track record.

Peruse the winners of the big literary awards – National Book Award, Pulitzer, Pen/Faulkner – and you’ll find a few outliers (Saul Bellow, Philip Roth, Don DeLillo, John Kennedy Toole), but in general the majority of prize-winners tackle dramatic subjects using dramatic voice and tone. Sure, humorists like Twain and Vonnegut wiggle into the conversation of “serious” literature. But these are the rare exception. Over the past sixty years maybe a dozen comic novels or collections have taken the top prize – in all major awards combined.

The disparity is equally pronounced in film. According to filmsite.org the Best Picture Award has been given to a comedy just 14% of the time (and that’s only tracking data up until 2001; anecdotally, I can’t remember a full-on comedy winning in the past seventeen years). Sure, a few have been nominated, but not many; and the fact that they never win tells us a lot about how our culture ranks their importance.

(Let’s not even mention humorous songs. These get banished to the novelty graveyard faster than you can say, “Don’t Eat the Yellow Snow.”)

So it’s apparent that our cultural critics poo-poo the value – the seriousness – of a good laugh. Maybe that shouldn’t be surprising. Even philosophers have historically beaten up on comedy like a bunch of drunken footballers.

However, there might be hope. The tide may be turning. New research has discovered all sorts of evidence that comedy is no joke.

For starters, people who dig comedy are smarter. Plain and simple. Psychologists now say that understanding jokes is directly related to intelligence and social IQ.

Then there are the numerous health benefits of laughing: stress reduction, lowered blood pressure, improving your immune system, and even “stimulating your organs” (woah!).

And a couple of years ago, Writer’s Digest came out with a cool list of the storytelling benefits of comedy.

By the way, I’m not arguing that comic fiction is better or more valuable than dramatic. I’m saying down with these sorts of stratifications! There’s room in our lives for all kinds of art.

The truth is that humor is a powerful way of coping with, raising questions about, and addressing the grave, troubling, frightening issues. After all, “Suffering is the destiny of all of God’s creatures; but to laugh in the face of suffering . .. that is distinctly human.” Someone famous said that, didn’t they? Wait, I said it. It sounds kind of right to me, though. Anyone can suffer, but to bring joy out of suffering? To raise questions about inequality, war, life, pain, and death while also making us laugh? That’s special. But it’s not simply a matter of giggling at agony; it’s that laughter brings us together. It binds us.

There’s a feeling of connection in sharing a joke. Humor welcomes us into its world. Humor takes us by the hand and says, “You’re going to like it here.” Humor lets our guard down: not only the guard of the reader, but of the writer. Humor embraces cognitive dissonance and critical thinking, and perhaps most importantly, humor is democratic.

It’s the voice of the people. In a day and age where diversity is crucial; when more than ever we strive to become a multicultural society and finally live up to the promises of our American Dream, in which all people are created equal – in this day and age, embracing the concept of comedy as serious literature might be the key. Laughter is the song of humanity, the salve for our burns, the spigot for our grief that floods the parched soil of tragedy with life-giving water. (Exaggeration is another nice form of comedy.)

But don’t just take it from me. Take it from those philosophers, who eventually came to value the democratic power of laughter: “In comedy there are more characters and more kinds of characters, women are more prominent, and many protagonists come from lower classes. Everybody counts for one.”