Creative writers know that physical description is among the most essential tools for establishing a character. How a person walks and talks; the clothing they wear; their hairstyle; how they chew and fidget and fuss, or sit stoically; the way they smile, frown, or stare blankly. These can provide terrific insights into our characters. However, merely listing the gestures often isn’t enough.

Creative writers know that physical description is among the most essential tools for establishing a character. How a person walks and talks; the clothing they wear; their hairstyle; how they chew and fidget and fuss, or sit stoically; the way they smile, frown, or stare blankly. These can provide terrific insights into our characters. However, merely listing the gestures often isn’t enough.

In workshop stories, I often see exchanges like this one (which I invented):

“I’m really happy you could meet me today,” he said. He gave her a small smile.

She looked up at him. “I love this restaurant,” she answered.

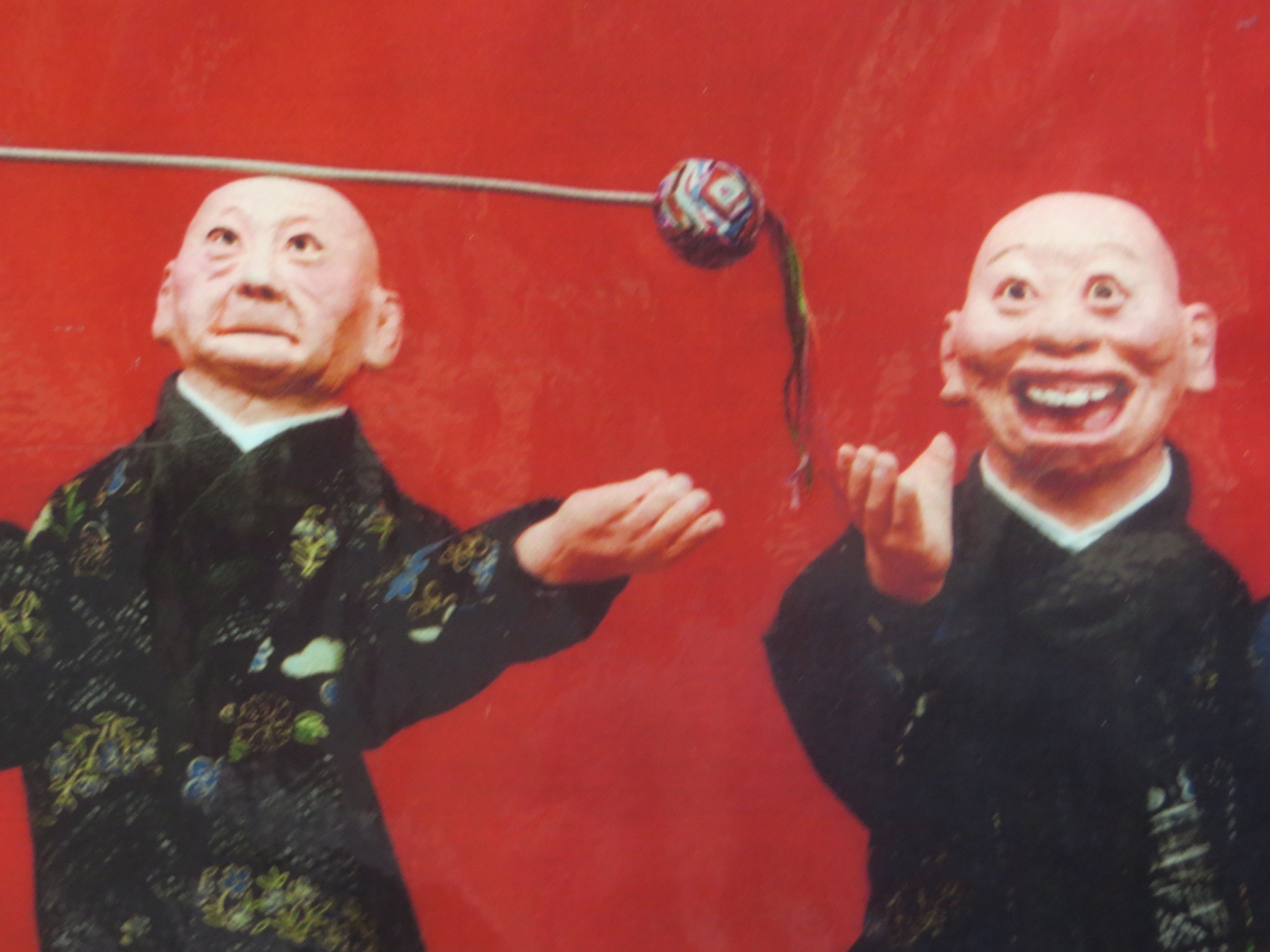

In this brief moment, we have two gestures – a “small smile” and a “look.” That’s a fine place to begin, but as written, these are simply stage directions. It’s as if the writer is merely puppeteering the characters, giving us a visual. The actions aren’t telling us anything about the characters, about the situation, about the emotional register of this moment. Is this guy actually happy? Is she happy? Or are they sad? Worried? Are they flirting? Are they ex-spouses who haven’t spoken in months, with a history of conflict between them? Is there resentment, love, nervous excitement? What are these gestures telling us?

Students often express hesitance about “slowing down” the action of the story in order to give backstory about the characters. They say they don’t want to bog down the piece with paragraphs of explication about who these people are and what brought them to this moment.

My answer is this: You don’t have to slow down the action. Weave the backstory into the action. Make it part of the scene. Connect the gestures to the characters’ backstory. Every gesture should reveal something: the character’s personality, psychology, desires, conflicts. Make the gestures work for you.

Here’s a passage from Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar:

Mr. Willard eyed me kindly. Then he cleared his throat and brushed a few last crumbs from his lap. I could tell he was going to say something serious, because he was very shy, and I’d heard him clear his throat in that same way before giving an important economics lecture.

Notice that Mr. Willard doesn’t simply “eye” the narrator. That might be misconstrued as creepy. Instead, he eyes her “kindly.” That’s helpful to the reader; it gives us something about the mood, the tone. Next, he clears his throat and brushes crumbs from his lap. Is he nervous? Is he about to say something? People tend to clear their throats when they want to say something. Sure enough, Plath makes it clear with the next sentence.

But most importantly, she adds another line that connects Mr. Willard’s throat-clearing to the characters’ shared history. We learn that he is shy (therefore, they know each other). We learn that he was a teacher, specifically an economics teacher, and she must have been his student. The gestures aren’t only stage direction; they forward the plot and deepen our understanding of the characters. And they haven’t slowed down the scene.

Sometimes simply choosing a compelling verb can do wonders for establishing character. Here’s an example from James Joyce’s Ulysses:

Then, suddenly overclouding all his features, he scowled in a hoarsened rasping voice as he hewed again vigorously at the loaf:

‘For old Mary Ann

She doesn’t care a damn

But hising up her petticoats…’

He crammed his mouth with a fry and munched and droned.

Notice how much work Joyce’s verbs are doing. “Overclouding all his features” makes me think this guy is in a bad mood. And then he “scowled” and “hewed . . . vigorously the loaf.” He’s eating, but he’s not just eating: he’s eating violently, piggishly. He sings a dirty little ditty, and then he “crammed his mouth with a fry.” There’s aggression in that verb. He’s literally stuffing his face.

Overclouding, scowled, hewed, crammed, munched, droned.

From those six words, I know quite a bit about what kind of dude this is. And I’d rather eat over here, thank you.

Flannery O’Connor is among the best at giving gestures with meaning. She often uses an “as if” structure, and it’s a technique you can easily apply to your own writing. Quite simply, she describes a gesture or expression, but then she adds one – or two, even three – similes that start with “as if,” similes that develop the character and the conflict.

From The Violent Bear It Away:

Rayber continued to speak, his voice detached, as if he had no particular interest in the matter, and his were merely the voice of truth, as impersonal as air.

As a writer I would be tempted to quit after “his voice detached,” which gives us something important. But O’Connor keeps pushing it. In what way is his voice detached? The first clause tells us Rayber is talking as if he doesn’t care about the topic. Then the second part really elevates the simile: he has “no particular interest” because his “voice of truth” is absolute. He has no need to argue passionately.

And finally, still not satisfied, O’Connor pushes it once more: “as impersonal as air.”

To me, this last clause makes the whole gesture. In his own mind, Rayber’s logic is like an invisible, ubiquitous, and necessary force. No person can live without air; it is all around us at all times. And now the reader truly sees the full extent of the character’s ego.

The most important habit a writer can develop is to read like a writer. So the next time you’re reading, pay special attention to the ways the author uses gesture and detail to build character, to bring us closer to their conflicts. And then, as always, don’t hesitate to rush to the keyboard (or pen and paper) and use their techniques in your own writing.