A particular kind of rejection exists, and while all rejection burns at some level there’s a point in a writer’s life when the people they have surrounded themselves with, their community and their friends and their rivals and their lovers, start to rise on stars so fast and brightly sharp, that rejection for this writer who has been left behind, down here on the earth, becomes something new, something beyond.

A particular kind of rejection exists, and while all rejection burns at some level there’s a point in a writer’s life when the people they have surrounded themselves with, their community and their friends and their rivals and their lovers, start to rise on stars so fast and brightly sharp, that rejection for this writer who has been left behind, down here on the earth, becomes something new, something beyond.

I’d like to try to characterize that kind of rejection here, so we can better understand it. So we can better learn to live with it.

***

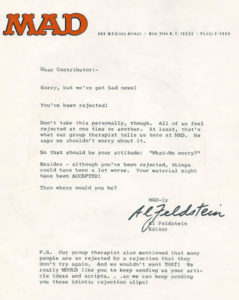

We wanted to let you know that it made it further in our reading than many submissions do and though we won’t be publishing it at this time, we do hope that you’ll send us work again.

This thing I’ve created, boiled down to it, it, it, a compliment that bee stings. I’m only a little allergic, only want to take a little Benadryl nap.

***

Oh my gosh this is so strange—I was just writing you a long response to your piece! Well, congratulations! I’m glad it’ll be in print. Can you tell me where? Two of my reviewers who read it were very enthusiastic and I know would like to be able to see it.

In a recent job interview, I was asked about my dream publications and presses. I tried to explain to these lovely people—generous and kind writers and thinkers themselves, people who understand both the academic job market and the world of publishing thoroughly—that in my life as a professional writer I was smacking my forehead repeatedly against a maybe metaphorical, maybe not, ceiling. In the Dean’s conference room, I used my hands and gestured a lot, trying to indicate that my career as a writer is full of possibilities. My gestures were supposed to say something like, Given time, I’ll find new ceilings to smash.

But maybe I’m not hitting this maybe metaphorical, maybe not, ceiling right now at all. If I were, I should be breaking through—simply by force of repetitive strain against metaphor, against a hard surface. Instead, I’m collecting rejection notices, collecting new writerly scars.

But that voice, it’s rejection doubt, slimy like the crap left in my lungs since H3N2 took me down two weeks ago. As creators, we need to learn to hear that voice for what it is, for what it does to our minds and hearts—and our art.

Perhaps, the original metaphor stands. I’m close, tapping at the plaster, forming hairline fractures I know exist only because of the dust I find in my teeth and hair.

***

I got a chance to read into this today, and while it’s a really strong project (truly, I think you’re such a talented writer!), I’m afraid it’s not a perfect fit for me. That said, I think someone else is going to snap you up with this one. But if that’s not the case, please do keep trying me! I continue to feel very confident that there’s success in your future.

Gritty chalk like substance on my tongue. And it doesn’t matter how much water I drink, how many times I brush my teeth, it binds, invisible.

Form rejections hurt. Because someone pressed a button. Someone clicked decline or nope or not-for-us-at-this-time or haha-they-thought-they-were-good-enough. And that click, it didn’t take much time on the part of the clicker. It happens. And then, for the clicker it’s over.

For the writer, it’s a new email notification after an already too hard day. Or it’s three rejections in a row. Or it’s a week of rejections. Or it’s the flu and one really painful slap to your writer’s heart.

But I’ve digressed…

***

This other kind of rejection is personal. It’s personalized. It’s a balm meant for that soon-to-be-wound. Words we’re supposed to cherish, to pin up on our walls or Pinterest boards, to ease the pain of this hurt—and the ones to come.

But maybe we’ve never talked about how that balm is salt, how salt grates against raw skin, how the burn travels on neurons, lingers, stays, imprints on a part of us that’s critical to the art we practice, how salt kills grass.

Maybe we’ve never talked about how kindness can be unkind.

As practicing writers we will always be rejected. It will never stop. Editors and readers and agents and bookstore clerks who don’t believe you’re the person who wrote the book you’re asking if you can autograph. Even TwitterBots will reject us. That’s a simple fact of what we face as writers.

As humans we will always be rejected. Learning how to process it is part of learning how to live. The moment we think we’ve found the last ceiling, the moment we stop learning, stop hurting, stop bouncing back, stop trying to get rejected, the moment these things happen I believe we’re no longer alive.

Rejection is the litmus test. Around my writer’s desk, metaphorically of course, you’ll find little strips of used filter paper stained by water-soluble dye made from lichens. Around your space, I hope you find this too and recognize the beat of your heart, the oxygen that animates what you are in this life.