I’m at dinner at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference – 250 writer types in one huge room divided up into tables of four, six, and eight. The voices are pitched high. Alcohol, sleep-deprivation, and all-day-and-all-night book-chat contribute to the general hysteria of neurotic people from all over the country eating together with many strangers – way too many strangers. The young woman beside me (whom I’ve just met) is shy, and so, socially responsible citizen that I am, I try to engage her in conversation, try to “bring her out,” as my mother would put it. Not meeting my eyes, she says that her name is Julie. The other two people at the table (whom I’ve also just met) do their parts to conquer Julie’s shyness – it’s a spontaneous and vaguely humanitarian project that distracts us from the anxiety we feel over the general dining room hubbub.

Julie turns out to be a good sport. She allows herself to be brought out. More accurately, she tries to be polite by answering our questions. She has a surprisingly snappy, street-corner way of speaking. At first she’s reluctant to say much, but as the conversation goes on, she releases information in rapid bursts of sentences punctuated by awkward pauses during which she blushes and stares at her plate. Julie charms us – she’s making such an effort not to be surly toward us and to enter the spirit of her first real writers’ conference conversation. She reveals to us that although she’s from a working-class family in a working-class neighborhood in a working-class city, she’s now a student at Middlebury College. The college offered her a scholarship, and without knowing much about the place, she showed up and enrolled. She reveals to us that she’s doing okay at Middlebury even though it’s about the strangest place she’s ever been, and most of her time on campus she feels like an alien.

Okay, we’re doing fine, we do-gooder bringer-outer dining companions like this biography we’ve elicited from the shy girl. Apparently Julie is a before-version of Eliza Dolittle, and we’re eager to contribute to her education and improvement. We ask her which writers on the Bread Loaf staff she listed as her preferences for a manuscript-reader. Julie shrugs and says that the only one she knows anything about is Larry Brown. She’s never heard of the others.

Okay, we’re doing fine, we do-gooder bringer-outer dining companions like this biography we’ve elicited from the shy girl. Apparently Julie is a before-version of Eliza Dolittle, and we’re eager to contribute to her education and improvement. We ask her which writers on the Bread Loaf staff she listed as her preferences for a manuscript-reader. Julie shrugs and says that the only one she knows anything about is Larry Brown. She’s never heard of the others.

This conversation occurs somewhere around 1992 or 93, in Larry’s first year on the Bread Loaf faculty – he’s an associate staff member and not nearly as “well known” as Tim O’Brien or Nancy Willard or Ron Hansen or Francine Prose or Nicholas Delbanco or the other members of the fiction-writing staff. We three dinner companions eagerly offer Julie our comments about our favorite writers with whom she might work – if it doesn’t work out with Larry Brown – in the coming days of the conference. Julie listens politely but finally shrugs and says she hopes she gets assigned to Larry, he’s the only reason she came up here, she really admires his writing.

About this time I glimpse, up at the far end of the dining room, Larry Brown himself standing up and excusing himself from the table where he’s been eating. From the previous year’s conference, when Larry and I became friendly acquaintances, I remember that after dinner he customarily leaves early like this to walk outside and have a cigarette on the porch of the inn. An irresistibly bright idea flashes into my brain. “Would you like to meet Larry Brown?” I ask.

“Oh God no!” Julie says. She looks as if I’d suggested we go out to the highway to watch a car run over a chipmunk.

My friends, I know I should have respected Julie’s wishes in this matter, I know I did the wrong thing, and my excuse makes me feel even worse than I ordinarily do about my social blunders. I was a victim of that strain of social agitation peculiar to writers’ conferences – low-level celebrity-itis. Ostensibly I was out to do the right thing, to introduce a fan to a writer and to give the writer the pleasure of meeting someone who has a passion for his work. But really and truly, I know I was just showing off and trying to increase my stature in the eyes of the people with whom I’d eaten dinner by demonstrating that I was pals with Larry Brown.

I stand up and speak to Larry as he makes his way down the dining-room aisle toward the exit. I tell him there is someone here at my table who wants to meet him, and in his affable way, he says, “Okay – sure.” I go ahead and make the introduction.

As I carry out my little mannerly performance, Julie blushes deeper than I would have thought possible. She might be flashing her eyes up toward Larry’s face, but I don’t see it. She might be moving her lips or moaning to herself, but I don’t see or hear that either. I do see her sitting with her head bowed and her shoulders hunched as if she’s in pain.

Larry Brown speaks to Julie. When she doesn’t – or can’t – reply, he finds a way to go on talking to her as if she has replied. A shy person himself, Larry seems to understand Julie’s plight, and with an eloquent social grace, he carries us all through the awkward situation. And of course the others at our table play their parts, too. Except for Julie, we all talk, we make chit-chat, we smile and laugh, and so the introduction reaches its proper conclusion. Larry tells Julie that it was great to meet her and that he looks forward to talking with her again. “And now if you’ll please excuse me,” he says, giving us all a grin and a nod, then making his way toward the dining-room door, the porch, and his well-earned after-dinner cigarette.

For a long moment the four of us sit in silence. Julie’s behavior during the introduction has been mildly shocking – I personally have never seen anyone quite so paralyzed by a social circumstance. The other two do-gooders and I begin awkwardly trying to construct a new conversation, when suddenly Julie interrupts us, “How could you do that?!” Her eyes are blazing at me, and it’s evident that her former shyness has been converted into anger.

I make my explanations, of course, and resort to such social skills as I have, which are adequate for most situations. In fact, I feel that in spite of my questionable motivation, I’ve acted correctly, I’ve made it possible for Julie and Larry to become acquainted in the days that follow, now she can get to know him as a person. And how can that be other than a good thing? I yammer on and on, feeling a hot mix of guilt, self-righteousness, teacherly condescension, and social desperation.

“You don’t understand!” Julie blurts, interrupting me mid-sentence – though it’s a disposable sentence, one that I’m happy enough not to have to finish. Julie has raised her voice enough to make the people at nearby tables shut up and listen to her.

“I used to go to my classes and walk around campus and be around these people all day,” she says, and she looks around the dining hall in a way that suggests that she means us. “And then when I finished my work, which was when everybody in my dorm had pretty much gone to bed, I stayed up late, and I read these stories by Larry Brown, and I thought, all right, thank god, at least there’s somebody somewhere who lives in the same world I do – somebody who knows who I am. Larry Brown was my friend in the early morning hours at Middlebury!”

Julie’s soliloquy ends abruptly. To fill the silence, I ask her in my softest voice, “And you never wanted to meet him?”

She actually shouts, “No!” Her face is both furious and pleading. A pocket of silence surrounds our table – we have the attention of a couple of dozen people. Everybody waits for something violent or grotesque to happen, but both Julie and I have come to the end of what we can say. Then someone finds a way to lighten the mood with a comment, and someone else responds, which helps me to find a way to apologize to Julie, and she manages to nod and let it go, and of course our dinner companions pitch in to help ease the awkwardness.

And that’s really the end of my story. It seems to me a literary parable – or maybe it’s more like what I understand a zen koan to be, a parable that’s paradoxical, mysterious, open to interpretation. Ideally, I’d stop right here and just let you hold in mind the drama of Julie and me and Larry Brown at dinnertime up at Bread Loaf. But I can’t resist making this assertion: To read a book is to choose the company of the author.

With a book (of artistic merit) it’s always the case that the art and the artist are so incorrigibly, undeniably, and inevitably connected that to experience the one is also to experience the other. It’s not by accident that we use such phrasing as “Have you read Faulkner? What do you think of Jane Austen?” When you read Absalom, Absalom! or Pride & Prejudice, you are in fact experiencing the human beings who created those books.

Now for the writers and artists among you, I want to offer both a caution and a comfort.

The caution is that if you try to write a good book, no matter how artful it may be, you’re out there. You’ve made yourself vulnerable to strangers, you’ve displayed yourself to the public, you’ve walked downtown naked. In fact, I sometimes think of artists as being a high order of prostitutes. And when I’m doing book-signings, sitting by myself at a little table with stacks of my books just sitting there untouched as the customers stream by, I think maybe I’ve got it wrong about the high order – maybe we writers are the absolute lowest order of prostitute.

The comfort is that as a fiction-writer or poet or personal essayist, this is what you’ve got to offer – yourself. So you don’t have to try to be anything or anybody other than yourself. Pshew! – what a relief that is. In your art, you can put on many masks and speak in various voices, but ultimately they’re all versions of you – as the people in your dreams are all, finally, you. The self is the basic stuff. The art is directed toward transforming that self into something beautiful made out of words. Quite often that transformational act is an act of discovery – in carrying it out, you come into possession of a self you didn’t really know you had.

My faith – a word I don’t use casually – in art is located right here. In “working” the self as one must work it in order to create art, one may discover that one is a cowardly, duplicitous, greedy, and insensitive weakling. But in coming to terms with all those dreaded negative qualities, one may also suddenly see that one possesses a peculiar integrity, a surprising strength of will, and an astonishing capacity to love. To catch a glimpse of the angel, you’ve first got to have a good hard look at the whore, and they live at the same address.

So that leaves just this one last question before us: Exactly why didn’t Julie want to meet Larry Brown, the author of the books that had kept her company in her lonely late hours at Middlebury College? At the time Julie didn’t explain. She went no further than her fiercely and poignantly shouted “No!” But I don’t mind saying what my own experience has taught me – that the person who lives in a work of art is not the same person who walks around among us on the face of the planet. An obvious and unsettling fact is that we look to great artists to be great human beings, while they demonstrate to us again and again that outside of the practice of their art, they’re ordinary, imperfect people. Often they’re quite unattractive. Sometimes they’re downright despicable, as if they feel they have to compensate negatively for the beauty they’ve produced in their work. I venture to say that artists are always fallible and usually fallible in ways that offend us or hurt us when we find them out. So whatever her reasons were and however emotionally wrought up she might have been, Julie was taking an extremely sensible position. No way was she going to be disappointed by Larry Brown the human being.

My friend Elaine Segal has written an illuminating fable entitled “The Progress of the Soul,” in which she says that “There was no mistaking the soul for the self.” The Soul is perfectly innocent – it lacks memory, understanding, and fear; its single virtue is that it recognizes “the very strangeness [of the world] before it,” whereas the Self is manipulative, vain, greedy, etc. So if I were to apply that fable to what I’m trying to discuss here, I’d say that by working the Self so rigorously to make a book, the author – with a great deal of luck – manages to invest the writing with some of his or her Soul. And this purification is what I’m going to guess that Julie understood with such passion: She’d already become acquainted with the man’s soul – meeting him in person could only be a violation of a relationship she greatly valued. What she managed to convey to me with her “No!” that evening in the chaos and babbling of the Bread Loaf dining room was wisdom. It’s taken me only about thirty years to hear it.

Coda:

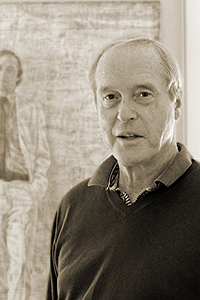

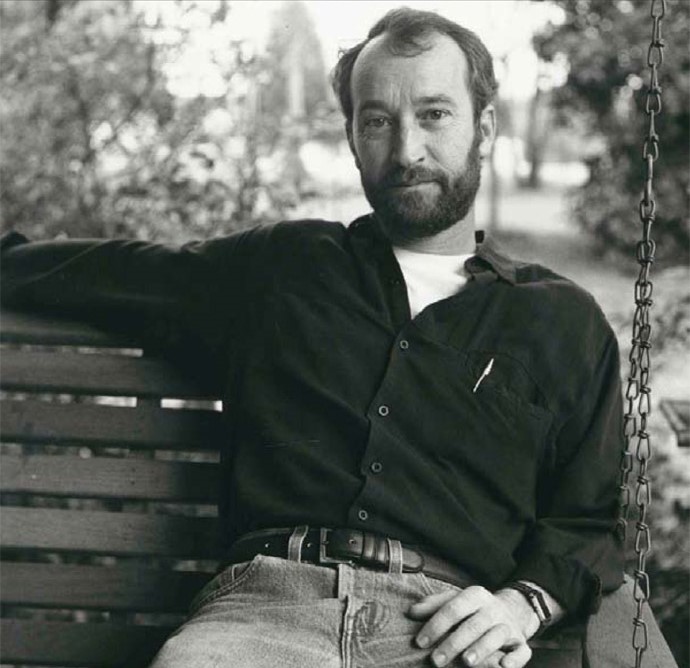

Larry Brown died of a heart attack in November 2004 at the age of 53. Here’s the link to his obituary in The New York Times: