Literary truth is entirely a matter of wording and is directly proportional to the energy that one is able to impress on the sentence. It reanimates, revives, subjects everything to its needs.

That’s Elena Ferrante, the Italian author of the much-lauded Neapolitan novels, in an interview just published in the Paris Review. And I’m sure she’s right—that is the truth about literary truth. You can’t have it, not in any genre, if, as she earlier states, “the writing is inadequate.” But say the writing is not only adequate, but exquisite! What about the actual truth—the truth-truth—in a work that claims to be nonfiction? Does it matter at all? For how long? And who gets to decide?

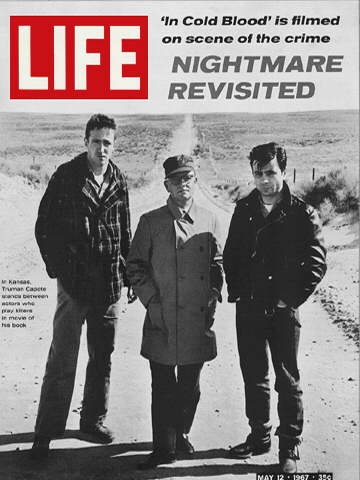

I’m thinking about In Cold Blood by Truman Capote. Beautifully written, right? But is that what mattered when it was first published? Is it all that matters now? Why did he call it a “nonfiction novel”? Was he inventing a genre, or only wanting it both ways? And—if that’s what it was (the latter)—so what; what’s wrong with that?

Backing up—I get regular emails (A.Word.A.Day, almost daily) from Wordsmith.com: wouldn’t you know the day I was scheduled to talk about Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood (at the AWP Conference in Minneapolis), the word for the day was “expurgate”— and its definition: “verb tr.: to remove parts considered objectionable.” Hilarious. There I was in my hotel room putting the finishing touches on my tiny talk—this had to be a sign, a directive; for me, of course, not for Truman Capote. If you were to expurgate In Cold Blood, it’d have no blood at all. The best parts are the objectionable parts, right? But are they objectionable? Or are they only the best?

In Cold Blood, billed by the author (as noted) as the first “nonfiction novel” (although his assertion is debatable—just about everything about Capote is debatable, after all), was published half a century ago this year: hence the occasion—the AWP event—an opportunity to consider the book’s legacy and relevance today.

But let me back up again: it was 1969. I was 12. The Clutters had died ten years earlier; the book had been published three years before. I read on my back in a sun-filled room (mine: I had a big bay window, and a chintz bedspread pulled up over my knees); it was one of those days when your parents keep urging you to go outside, get on your bike, get some fresh air…but I was cooped up with Truman Capote. I could not get enough. I read the way we read fiction—or the way we did when we were kids, which is why we fell in love with writing in the first place, yes? I mean to say, if Capote had ruled out first person presence and point of view (a requirement, said he, of his brand-new form), I had not: I believed in what was happening in that farmhouse in Holcomb, Kansas as if I were dreaming it up all by myself. It was Nancy Clutter who got to me, of course—Nancy, who was 16 and perfect. She had a horse and a boyfriend; she was good at everything; everyone loved her. Nabokov has counseled us against identifying with characters. That isn’t our job he explains in his invaluable essay, Good Readers and Good Writers. And even so that’s how I read fiction back then, and how I still read it when I get lucky: for the duration (at the very least), I claim it as my own.

But let me back up again: it was 1969. I was 12. The Clutters had died ten years earlier; the book had been published three years before. I read on my back in a sun-filled room (mine: I had a big bay window, and a chintz bedspread pulled up over my knees); it was one of those days when your parents keep urging you to go outside, get on your bike, get some fresh air…but I was cooped up with Truman Capote. I could not get enough. I read the way we read fiction—or the way we did when we were kids, which is why we fell in love with writing in the first place, yes? I mean to say, if Capote had ruled out first person presence and point of view (a requirement, said he, of his brand-new form), I had not: I believed in what was happening in that farmhouse in Holcomb, Kansas as if I were dreaming it up all by myself. It was Nancy Clutter who got to me, of course—Nancy, who was 16 and perfect. She had a horse and a boyfriend; she was good at everything; everyone loved her. Nabokov has counseled us against identifying with characters. That isn’t our job he explains in his invaluable essay, Good Readers and Good Writers. And even so that’s how I read fiction back then, and how I still read it when I get lucky: for the duration (at the very least), I claim it as my own.

I knew, of course I did, that Capote’s book was not just “based on” a true story (that’s Hollywood parlance by the way—based on, inspired by—these are the phrases screenwriters and producers use to let us know they’ve fudged the facts): that was undoubtedly part of the lure—that this terrible thing had happened to a real girl, a girl just like me (okay, nothing like me—no horse, no boyfriend, not dead—poor Nancy… I ached for Nancy). But not only “based on,” that’s my point: According to Gerald Clarke, Capote’s biographer, the author “publicly boasted” that “In Cold Blood may have been written like a novel, but it is accurate to the smallest detail—“immaculately factual.”” Clarke goes on to say, “Although it has no footnotes, Capote could point to an obvious source for every remark uttered and every thought expressed. “One doesn’t spend almost six years on a book,” he said, “the point of which is factual accuracy, and then give way to minor distortions.”

But he did give way to distortions, that we know. And he had to have invented—because he wasn’t there! So—does it matter? Once a work is part of the canon—once it informs the culture as this book has, is it, perhaps, a waste of time to worry about the rules? In any case, I can tell you, if you’re 12 years old, and you’re death-obsessed, as very many of us 12 year olds were (for me that was also the year of A Separate Peace, Death Be Not Proud, The Diary of Anne Frank, and Roald Dahl’s macabre Kiss, Kiss) the rules (not that you knew them at the time, but say you had—Genre, wtf, who cares, you would have said then—and here’s an awful thought: were you more enlightened then?) would seem not to apply.

Flashing forward (I hope I’m not giving you whip lash): Every time I went to jot down my thoughts about the book I got stuck in just this way—as if I’d been chosen, me of all people, to come at the book from this particular angle. But of course that wasn’t why the moderator (smart, insightful Kelly Grey Carlisle) had contacted me—it couldn’t have been; she had no way of knowing how strident I’ve become about genre blur—about the responsibilities of writing nonfiction. What she did know, she must have, was that I’d written about a murder, my father’s, in a book called Bigger than Life.

And yet. I wasn’t willing, at first, to zoom in from that perspective—as if I have some particular purchase, or privilege, or prescription for writing about trauma. How long, how many times, I asked myself, can a person milk a trauma? And so, this time, for this panel—and this was an act of avoidance, I guess—I resolved I wouldn’t resort to that strategy. This time I’d change it up. Therefore I engaged in an informal survey. I emailed a bunch of my colleagues—a dozen smart, successful writers—and asked them to tell me in a line or two what they thought about In Cold Blood.

The first responder, a journalist in her mid-50s, who, like me, had read the book as an adolescent, wrote that she was (again, like me) “swallowed up in the story.” When I asked if it occurred to her that Capote had made any of it up, she answered that it was “written with such authority that I believed in it.”

Another friend—a guy pushing 60 who pens novels and writes for television—had read much more recently, as a middle-aged man. He was “blown away,” he said, “by the prose, the storytelling, the essential invention of an entire genre.”

And another novelist, who remembers the book from high school in the 70s, told me that, having to do with the title, perhaps, she’d felt cold as she read, and “a little sick, the way you feel when you suspect yourself of prurience. The narrative distance probably also contributed to that feeling.” She added, “I believed every word.”

Two more: First, from Nathan Deuel, a young nonfiction writer (he has to be named, because I can’t take credit for his answer, though I wish I could): “It’s a beautiful book! But it’s also a big hash, right? I could imagine a great course that involved Capote, D’Agata, Dillard, etc. Details, Danger, Destiny, and Deceit.”

Last, from a New Yorker staff writer, also in her 30s, who read the book a year or two after she graduated from college: She was “thrilled” by the writing, she said, though she remembers wondering, “How is this NON-fiction?”

Good fun, my survey, though it didn’t change anything for me; it only confirmed my misgivings, which have more to do with my own way of reading, I fear, than with the book, itself. I found myself wondering over and over: Did Capote get away with something when he published In Cold Blood? Would he get away with it now? To even entertain the question makes me wonder when exactly I became so rigid in my expectations and standards? And now: face to face with In Cold Blood, do I have the courage of my relatively recently-cultivated convictions? Are my notions about genre worthless to me in the face of art? (At what point in time do we decide it is art, whatever it is? I want to know that, too.)

Here’s another quote, this from a 1957 interview in the Paris Review, two years before the Clutters were murdered. A writer called Pati Hill asked Capote if he had “definite ideas or projects for the future?” He answered:

“Well, yes, I believe so. I have always written what was easiest for me until now: I want to try something else, a kind of controlled extravagance. I want to use my mind more, use many more colors. Hemingway once said anybody can write a novel in the first person. I know now exactly what he means.”

Hmmm.

As flattered as I’d been by the invitation to join Kelly Grey Carlisle’s AWP panel—it’s always flattering to be invited—as the months ticked by I began to suspect I had no business weighing in, not really. I’m not a journalist. Nor have I yet challenged myself to write about the experience of anyone I do not intimately know—which was the realization, in spite of my intentions, that prompted me to make a connection of sorts: because, come to think of it, back when I finally sat down and imagined murder on the page, I did, in fact, write in third person. But if it was the absence of an emotional attachment that allowed Capote to choose omniscience, it was just the opposite for me. I felt cornered. I chose third because I didn’t trust myself, not because I did.

The most frustrating thing about what happened to my father isn’t that it was unimaginable—though it was—it’s that I have to admit, first and always, before anything else (this is the problem of writing about your own dead, the ones who are real to you) I will simply never know. What was it like? Did he believe he was going to die? Did he have time to be afraid, or angry, or sad? Because I actually knew him—my father—I was unable to convince myself (as Capote had) that I could ever come close to knowing. And I judged myself harshly—still do—for pretending I could. I called the chapter “Conjecture.” And if I’m not sure what I think about In Cold Blood (not to compare myself to Capote, please don’t mistake me), neither am I sure how I feel about my own pages—about how, with the truth up for grabs (but forever out of reach), I nonetheless allowed myself to “reanimate, revive, subject” for the sake of “literary truth.” If “literary truth” is the end-goal in fiction, in nonfiction, even and especially when it’s the best we can do, it perhaps comes up short.

With all that in mind, and continuing to prep, I ran into an essay called “Ghosts in the Sunlight: The Filming of In Cold Blood,” written by Capote himself, in which he talks about his sense of disconnection on the set; how odd it was to watch actors impersonating murderers in the Clutter house—that’s where they filmed the movie!—at the actual house: “…eight years have passed,” writes Capote, “but the Venetian blinds still exist, still hang at the same windows. Thus reality, via an object, extends itself into art; and that is what is original and disturbing about this film; reality and art are intertwined to the point that there is no identifiable area of demarcation.”

Although he admits, on first viewing the movie, to experiencing a “sense of loss”: “Not,” he says, “because of what is on the screen, which is fine, but because of what isn’t.”

Ironic, no? As if the filmmakers were the ones who compromised? As if he did not?

You tell me.

Karen Bender is the author of the story collection Refund, published by Counterpoint Press in 2015; it is a Finalist for the National Book Award in Fiction, and is on the shortlist for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Prize; it was also a Los Angeles Times bestseller. She is also the author of Like Normal People, (Houghton Mifflin) which was a Los Angeles Times bestseller, a Washington Post Best Book of the Year, and a Barnes and Noble Discover Great New Writers selection, and A Town of Empty Rooms (Counterpoint Press).

Karen Bender is the author of the story collection Refund, published by Counterpoint Press in 2015; it is a Finalist for the National Book Award in Fiction, and is on the shortlist for the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Prize; it was also a Los Angeles Times bestseller. She is also the author of Like Normal People, (Houghton Mifflin) which was a Los Angeles Times bestseller, a Washington Post Best Book of the Year, and a Barnes and Noble Discover Great New Writers selection, and A Town of Empty Rooms (Counterpoint Press).