Kate Cumiskey lives with her partner Mikel in coastal central Florida. She has a social justice novel, Ana, forthcoming with Finishing Line Press, and a biography, Surfers’ Rules: The Mike Martin Story, forthcoming with Silent e Publishing; both will be out in late 2022. She is currently concentrating her writing to reflect her perspective of social justice without judgement or paternalism as regards homelessness, and continuing her work in meeting the needs of homeless human beings in her community. She also leads efforts locally to ascertain safety and educational fidelity for students within the public school system through boots-on-the-ground advocacy.

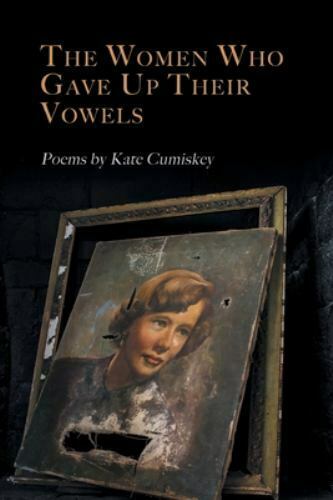

Our Poetry Editor, Bree Hoffman, read and reviewed Kate’s recent book of poems, The Women Who Gave Up Their Vowels and was lucky enough to also interview Kate about the book. The interview was conducted via email.

Bree Hoffman: “Candor” is the first poem in your book, and it lives up to the name by truth-telling right away. What was your thought process when opening the book with “Candor,” and what is the desired effect for the reader?

Kate Cumiskey: I’ll start with answering the second part of this question. This poem, I hope, serves as a bit of a warning to readers, “there be dragons here.” I don’t want readers to be surprised by the literal candor in the book. It’s important to me that writers speak truth, and with this book I particularly wanted to focus on truths we don’t normally speak out loud, but which do keep us isolated in that they make us feel alone. In fact, such things as hemorrhoids, death, and rape, while two of those are fortunately not universally shared, are common and lose a bit of their power when acknowledged as such. I had been struggling with a bit of inertia when this book was initially accepted by Finishing Line Press – how do we speak truth in such horrific times? – and I reread Candor to get myself back into the fray of writing what is happening to all of us, right now. FLP was gracious enough to allow the book to change with the rapidly changing, deadly times through the publication process. Candor had originally been the title poem of the book, but that too changed through this process. The title reflects my own grappling with deliberately losing my deep Southern drawl as a married teenager living in California, where nobody deigned to speak to me in public. I trained the South out of my voice, and I miss it. This book is an attempt not to recover those vowels, but to speak, now, with the voice I’ve developed on issues which are absolutely vital to me. So, Candor is a warning for readers.

BH: In poems such as “Dirge” and “Favoring Boys” your activist roots come through. How does activism influence you as a writer, and how do you hope to factor them into your work in the future?

KC: It is interesting that you choose “activist roots,” as I think of this book as very active in voice, and independent from my roots, so to speak. I do not tend to think of my parents as activists, but you are spot-on; certainly they were, both of them. I hope it is evident in the poems that my mother and I had a very complex relationship, but she was in fact the bravest person I’ve ever known. She did things I’d never dream of, and that I’d consider down-right dangerous, for example, always picking up hitchhikers no matter what, until literally the week before she passed away in 2017. That’s activism. She also reserved judgement on people outside her own circle, such as homeless individuals panhandling, saying judgement was for God-she’d give out money and when less radical individuals called her on that, saying, “what if they spend it on drugs?” She’d say, “It’s a tough life, maybe that’s what they need to get through the night.” My father was a NASA pioneer, and even though his designs were crucial to getting humans to the Moon and our technology into interstellar space, when I asked what he was proudest of in his career, he replied, “I couldn’t keep a secretary. Every one of them out-degreed me and went on in the Program. I helped them all do that.” Activism in the workplace, helping females move forward in what at the time was absolutely a male domain. So, yeah, activist roots. Right now, I’m working on a series of poems about withholding judgement. In fact, one of the central poems to that book, Cokeheads I Have Known, is forthcoming in an anthology, The Literary Parrot, Series Two. I am pushing myself hard to speak about our shared humanity, and to encourage readers to strive to leave judgement behind. Again, there be dragons here. It’s hard to examine your own boundaries.

BH: I noticed recurring themes of motherhood and generational trauma several times. Could you discuss why those themes resurface in your work?

KC: Again, you bring up something about the book I’d not noticed! Brava; I love it! I remember discussing what I was most concerned about in my work with my dear friend and mentor, Robert Creeley. He’d asked, and I responded, “Being labeled a ‘domestic poet’.” He replied with his fabulous candor, “Well, you are a domestic poet, but you’re in good company.” He was saying he too was a domestic poet. That long-ago conversation freed me of the concern, and I allowed my work to truly reflect my domesticity–what’s more domestic than parenthood? I took a sort of semi-conscious approach to this book, letting it be whatever it wanted to, even to the point of playing with, allowing myself to play with, voice in person. That evolved into my writing some of the easier poems first person, and dealing with more difficult topics, like that generational trauma you cite, in second person, and letting the poems stand that way. It’s subtle, but there, and I hope creates a bit of chaos and discomfort and puzzlement in readers. Like trauma does. I believe the deepest root of that trauma goes back to my father’s loss of his parents before he was eight; he was a Mississippi Depression orphan, son of a sharecropper and a teacher, and although he missed them, as a practical Christian he knew he would be with them again, and told stories about them as if they were just away for a while. Which, from a Christian perspective, they are. So, I really missed my grandparents growing up. In fact, as a small child in school I was confused by other children having two sets; I thought of my Atlanta grandparents, my mother’s, as my father’s parents, too, before such things were explained to me. It came as a real blow that I had missing grandparents. This deepened as it became very apparent I most resemble my paternal grandmother, who was also incredibly domestic, and a teacher; my mother was decidedly not. In fact, because I loved these things and she didn’t, she had me take lessons in sewing, cooking, even deportment and etiquette. Because back in the day a woman should be graceful and I was clumsy as a child, I also took dance lessons for several years; I still love to dance. As far as my work, the obvious answer is also that I use these underlying specificities in my past to attempt to connect with readers. It is important to me that each reader experience each poem differently; what the reader brings to the reading through their own past is as important to me as the words on the page.

BH: What advice would you offer to our readers about writing?

KC: Connect! Read! Reach out to writers whose work speaks to you, if they are living, and ask the questions you are burning to ask. Ask for help. If you are stuck too deeply in your own, isolating experiences, force yourself to look outward and write just what you see, sans analysis. Take a piece of rotting fruit, put it on the table, smash it to bits, and sit down and write that. Keep the self completely out of the work. That’ll get you writing. Work outward from there: write the doorway, then the hall, then the threshold. Then, write what’s outside that door.

BH: What does your personal writing process look like when you are building a book of poetry?

KC: It’s a mess! In fact, I’ve recently opened an office in a classic old building in order to grapple with my lack of organization, and am working on a schedule. Seriously, although outwardly I’m a bit of a mess, I’m actually pretty organized and disciplined. I keep poems in print and on the computer, and when they start to build up in number, I have a serious look at them to see if they belong in a group, in a book. And I am always sending out finished poems to find a home in a journal or anthology. My mentor Mark Cox worked hard with me on how to put together books when I was in graduate school, and I still use his method, which is deliciously physical. I find a space with a large surface area – The Women Who Gave Up Their Vowels was put together in my brother’s beautiful kitchen, in the afternoon overlooking Turnbull Bay, Atlantic Center for the Arts just visible on the opposite shore–and lay out the printed verses. I choose the opening poem, and circle until I find the poem which calls to it, which wants to be next. I keep going until the book is finished. Any poems left I simply hold for another day. Another book or spoken word venue.

Review

Kate Cumiskey’s, The Women Who Gave Up Their Vowels, is her latest and perhaps most intimate book of poems published thus far. In a recent interview with Superstition Review, Cumiskey said of its origins:

“The title reflects my own grappling with deliberately losing my deep Southern drawl as a married teenager living in California, where nobody deigned to speak to me in public. I trained the South out of my voice, and I miss it. This book is an attempt not to recover those vowels, but to speak, now, with the voice I’ve developed on issues which are absolutely vital to me.”

The Women Who Gave Up Their Vowels expands on this promise, and provides a candid, autobiographical collection of poems relevant to Cumiskey’s lived experiences. This includes the appropriately titled, “Candor,” a poem that opens up the collection and lives up to its name.

Cumiskey’s writes,

Write your history; write that fear at 2 a.m. the night your son overdosed. Write tile beneath your knees. Write rats in the kitchen, raccoons in the roof, your dog over the fence, gone all night.

I found Cumiskey’s poems to be moving and sincere in their attempts to reclaim ownership over her lived experiences. Her poems cover topics including sexism, assault, politics, loss, and hope for the things she cannot fix. It’s hard to separate the author from the poems in this particular collection, because the two feel so intrinsically linked, and it’s readily apparent when reading them.

Cumiskey writes,

Bit by bit my body settles into age: fractious, screaming all the way down. Only in twilight sleep I feel my lower jaw shift, relax, offset to the right, the side I sleep on. My mouth clamps, thin-lipped, crooked, and settles for sleep into Mother’s fighting look, the one she wears when will not be moved. Then I can rest. And it feels good like falling into my own skin.

(From “Just Lately I Feel My Body Settling”).

To purchase a copy of The Women Who Gave Up Their Vowels, head to Finishing Line Press. Congratulations and thank you, Kate!