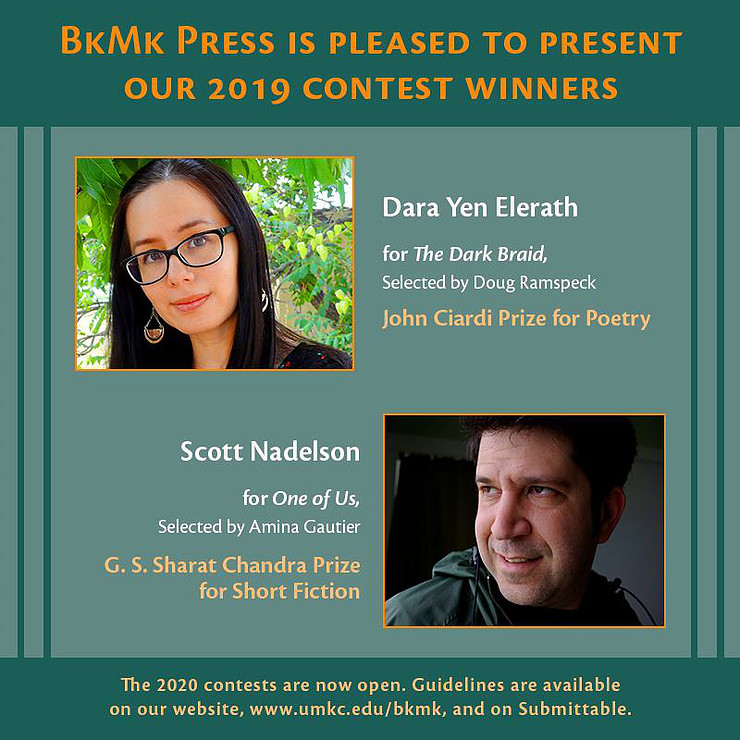

When the three poems of mine appeared in Issue 10 of the Superstition Review in 2012—“An Act of Ghosting to Avoid Complications,” “Like a Good Horse,” and “Vultures and the Constant Application of Them”—I had just experienced a creative burst after almost a year of not having the time or energy to write because of my job as an arts administrator at a state university and also because I had founded a Zen Center in Clarksville, Tennessee. And most importantly, I had become a father in 2011 and was spending as much time as I could with my daughter and wife.

I wrote these poems (and four others) after returning from a dai-sesshin (or intensive 7-day Zen Buddhist retreat) in California. I began my Zen Buddhist practice in 1994 at Haku-un-ji Zen Center in Tempe, Arizona, and my teacher, a Japanese Zen master, had ordained me as a monk in 2005. I’ve come to understand that a contemplative practice like zazen (often translated as meditation) is very much like what is often called “the creative process” (and I would extend that to include the “scientific method”). The practice emphasizes quieting discursive or conceptual thinking which makes room for the intuitive mind to enter and form new experiences of understanding (which relates to “solving” Zen koans). Contemplative practice is, in fact, the foundation or matrix for all wisdom traditions; however, writers and artists employ it all the time. Poetry, to me, is another manifestation of contemplation in action—like walking meditation, samu (or work practice; like sweeping)—where self-consciousness drops away and the intuitive appears and plays, albeit a serious form of play. In Zen Buddhist terms to achieve this state the practitioner must “break one’s bones and sweat blood,” which essentially means to establish a routine and put in the effort.

I had developed a rather careful writing practice when I was in the MFA program at Arizona State University. I meditated early in the morning, wrote in my notebook for at least two hours and would draft poems on my laptop in the afternoons. But this routine didn’t transfer into my life after the program. Once I entered arts administration, my free-wheeling life was curbed by my responsibilities which included travel, after-hours work at home, and attending programs, among other things. And yet I kept to the notebook writing and when I had the energy or time (vacations were limited to consecutive weeks) I would draft and edit one or two poems. I was slowly assembling a manuscript, or so I thought. However, whenever I sat down to review the manuscript, the poems just didn’t seem to be in harmony, and then one day, last year, I had an epiphany: I was writing two books, not one. One book continued my preoccupation with Iceland and reinterpreted its canonical history as well as my own biological family’s (versus my adopted family) history. The other book was poems I wrote out of my insights into Zen practice.

Like a good horse on who a whip alights, be earnest and energetic. By faith, discipline, vigor, concentration, and discernment of truth, expert in knowledge and action, aware, slough off this mass of misery.

Dhammapada: The Sayings of the Buddha, translated by Thomas Cleary, p. 49

So the poems in Issue 10, as I have mentioned, sprung from a sesshin and the notes I took at night under the covers of my bed. One poem, though, bridges the two books, “Like a Good Horse,” which turned out to be an elegy for my beloved Icelandic uncle, whose health after a nonstop working life was in decline. The title is borrowed from the first line of the Dhammapada, or the Sayings of the Buddha, from the penultimate verse in the chapter about violence: how violence against others is violence against oneself (i.e., on how important it is to cultivate compassion):

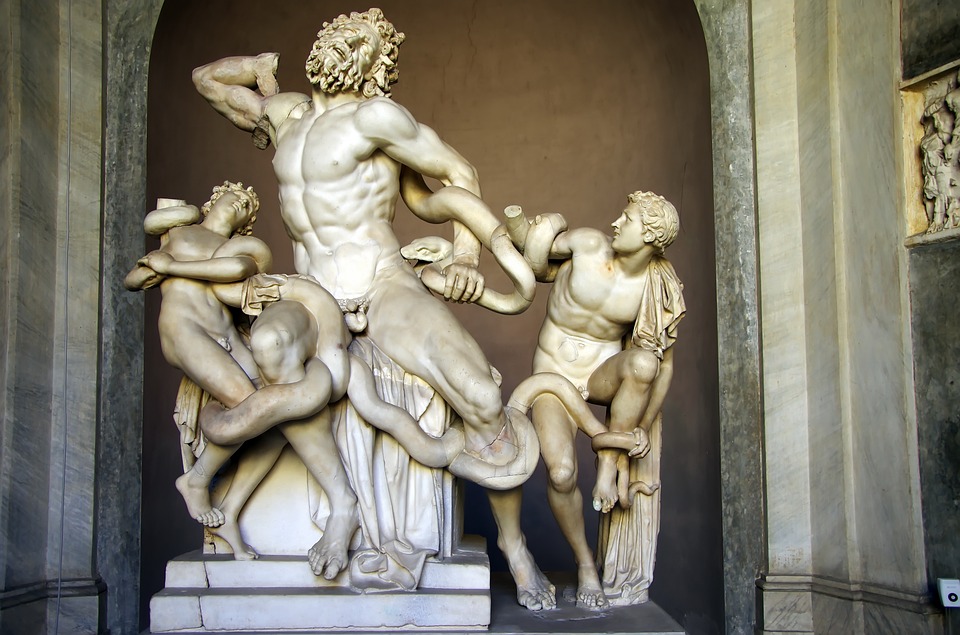

My uncle was a large and physically strong man but had a sweet nature, one that endeared him to every child that ever met him. However, there were men who, because of his legendary strength, wanted to take him on and thereby elevate their own prowess. My uncle, though, never succumbed to their taunts and actually abhorred violence. And so the poem.

Of the other two poems in Issue 10, “An Act of Ghosting to Avoid Complications,” is not about ending a relationship by suddenly disappearing. The term, “ghosting” was used by my Zen teacher to describe the activity of becoming the other. Dissolving one’s I-am self to join in a profound relationship with another person or even thing. And this definition should probably have appeared as a note at the bottom of the page. My bad. The other poem, “Vultures and the Constant Application of Them,” is about acknowledging and restoring our connection (as humans) to the natural world, from which we have become separate. So is it Zen? To me, yes, but perhaps not to some readers.

Returning to the subject of my notebooks and scribbling. Because I have amassed over 10 years (since my first book) of notebooks, I’ve begun to mine them, which led to the poem, “Desire, Speckled by Want,” in Issue 23. This poem incorporates an important Zen Buddhist theme, of developing compassion for oneself before one can expand it to others. It addresses obliquely the subject of my adoption and a feeling of loneliness I have always attributed to separation. The landscape, for me, is the interior of Iceland, where the barren stratified mountains lean into the floodplains with their alluvial fans. It is a haunted landscape that reflects extreme isolation. And the forgiveness sought in the final line is essentially that of my present self observing the past self, as an object, and thereby acknowledging that self’s struggle.